Grigory Teplov and the Sodomy Case in 18th-Century Russia

Nine serfs accuse their master of rape.

- Editorial team

“Having summoned him to his bed, first caressing him and holding out promises of reward, and in the end also threatening him with a beating, he forced him to commit muzhelozhstvo (literally “lying with a man”) over him.” This is a line from the interrogation of a serf peasant, where he accuses his master, Grigory Nikolayevich Teplov, of “muzhelozhstvo” (a historical legal and church term usually translated as “sodomy”) and of rape.

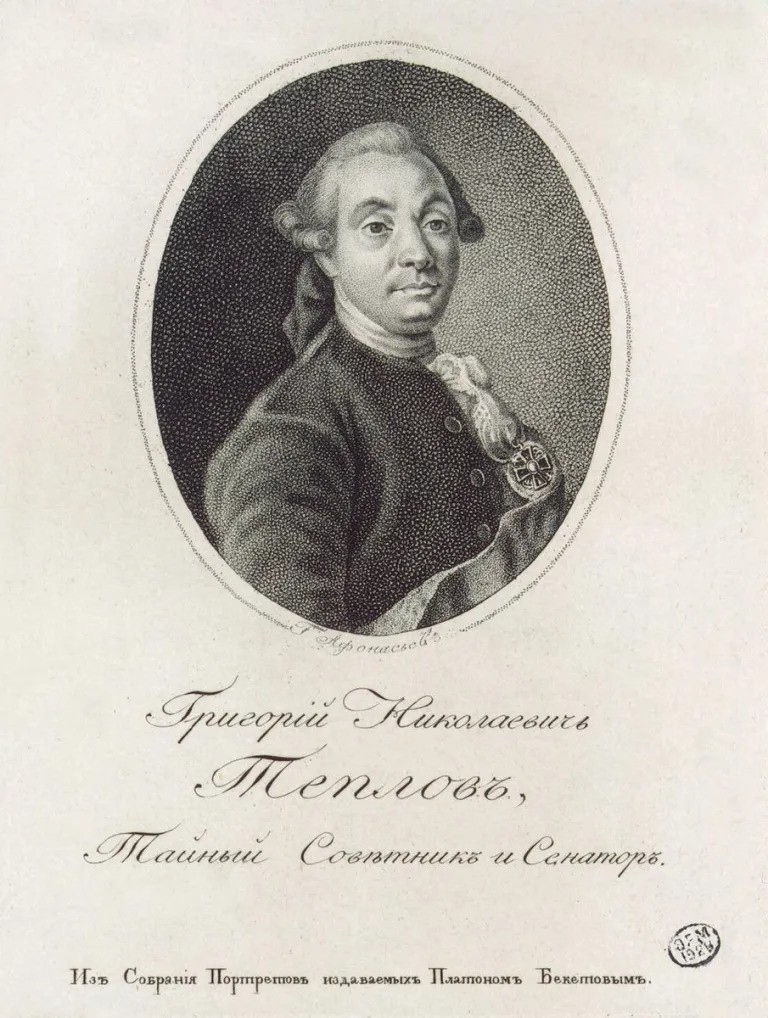

In the 18th century, Grigory Teplov did in fact make an unusual career for himself: he rose from a poor background to become a noticeable figure at court.

Before we look at the trial itself and its consequences, let’s first understand who Teplov was and how he climbed so high.

“… his vice was that he loved boys, and his virtue — that he strangled Peter III.”

— Giacomo Casanova on Grigory Teplov

Childhood and Youth

Teplov was born in Pskov, but sources disagree about the exact year: different dates appear, though 1711 is mentioned most often. In any case, his origins are described as modest. His father was a stoker — he heated and repaired household stoves. It is thought that Teplov’s surname came from this trade, deriving from the Russian root teplo (тепло), meaning “warmth.”

Teplov’s fate changed thanks to Feofan Prokopovich. He was a prominent church figure and intellectual of Peter the Great’s era, who supported Peter the Great’s reforms and worked in education. While travelling through Pskov, Prokopovich noticed a gifted young man and took him under his wing. In St Petersburg, Prokopovich ran a school at the Alexander Nevsky Lavra (a major monastery) for talented children from poor families.

Teplov studied well and was given the chance to continue his education abroad. He was even sent to Prussia for three years.

After returning, Teplov entered academic circles. At the start of 1742 he joined the Academy of Sciences, where he received the post of adjunct (roughly, a junior academic — an assistant to a professor). He worked on botany and, at the same time, lectured on Christian Wolff. Wolff was a German philosopher who was very popular in Europe at the time: he was valued for trying to build philosophy as a strict, “logically laid-out” system, where everything is explained step by step, like in a textbook. That is why, for many students and officials of the period, Wolff was a convenient “gateway” into philosophy.

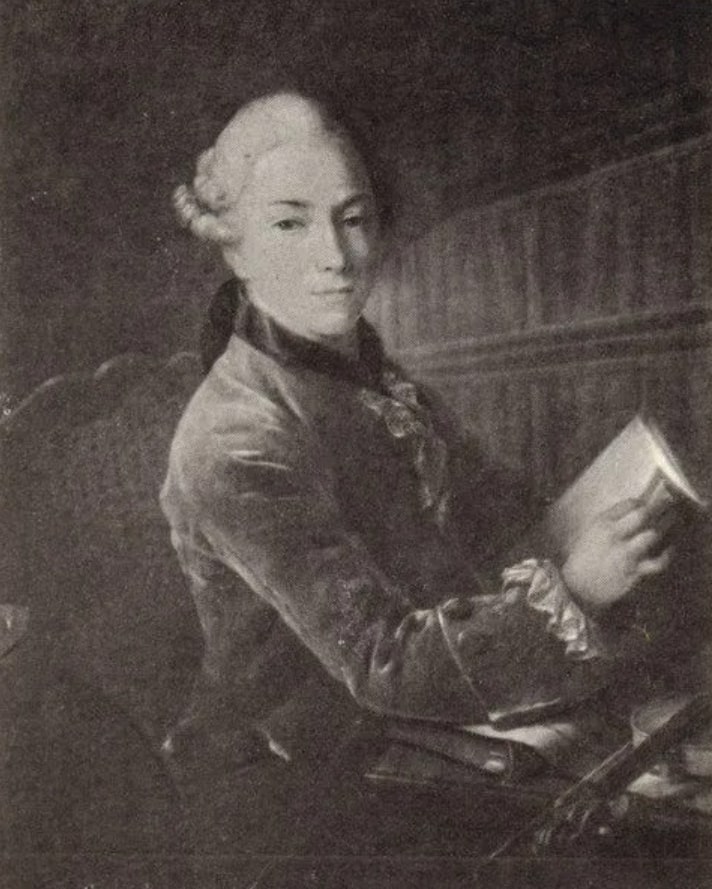

Alongside his studies and service, Teplov also painted. At Prokopovich’s school, visual art was considered an important part of education. Today, four of his works are known: one is kept in the Hermitage, and three are in the Kuskovo Estate Museum in Moscow.

Teplov painted still lifes in the style known in Russian as obmanki (“deceptions”). This is a colloquial name for the technique of trompe-l’œil — “deceiving the eye” — where an artist paints so that the viewer feels the objects are real, as if they were actually pinned to a wall or lying on a surface. However, painting stopped being Teplov’s main occupation, because his career became tied to dangerous political intrigues.

In 1740 he was drawn into a case connected with Artemy Volynsky, a nobleman accused of conspiring against the current regime. Among the evidence in the Volynsky affair was a genealogy — a depiction of a family’s origins. The idea was for it to emphasise the Volynskys’ connection to the Rurikids (the medieval ruling dynasty), which could have served as a basis for claims to the throne. Volynsky commissioned Teplov to create this piece.

In the end, however, Teplov avoided punishment. The work was destroyed in time, and Teplov managed to prove that his involvement was limited and technical. According to him, he only sketched the family tree in pencil under another participant’s supervision. Volynsky was executed, while Teplov was acquitted and released.

The Leadership of the Academy of Sciences

Count Alexei Razumovsky, Empress Elizabeth Petrovna’s favourite and lover, noticed that Grigory Teplov was highly educated and entrusted him with the upbringing of his younger brother, Kirill. Kirill was 15 at the time. Teplov became his tutor and guardian. Together they set off on an educational tour of Europe. Kirill studied in Königsberg, Berlin, and Göttingen, and then Teplov and his pupil visited France and Italy.

In the spring of 1745 they returned to St Petersburg, and just a year later Kirill — who had only just turned 18 — was appointed President of the Academy of Sciences. In the Russian Empire, the Academy of Sciences was the main state scientific institution. Appointing an eighteen-year-old to such a post was not the result of Kirill’s scholarly achievements — the decisive factor was his brother Alexei’s influence at court.

In practice, however, the Academy was run by Teplov. He was given several key posts in the Academy’s administration, and the main decisions passed through him. Within the Academy, Kirill Razumovsky carried out Teplov’s orders, and because of this Teplov could behave as if the Academy were a separate little state where he was the one in charge.

According to professors who worked at the Academy, Teplov’s leadership was poor. People expected the head of the institution to reconcile scholars and defuse conflicts. Teplov did the opposite: he intensified hostility among scientists and was constantly quarrelling with everyone himself.

Once, an anonymous pamphlet appeared at the Academy — a text with no signature. The pamphlet mocked and exposed scholars and sharply criticised Teplov himself. Teplov suspected the poet Vasily Trediakovsky and decided he recognised him by his writing style. After that, Teplov attacked Trediakovsky in two senses at once: he filed an official complaint about “improper behaviour”, and he summoned him and “threatened to stab him with his sword”.

Teplov’s sharpest and longest conflict was with Mikhail Lomonosov — a giant of the Russian Enlightenment, often likened to a one-man blend of Benjamin Franklin and Isaac Newton: a leading scientist and reformer who helped shape Russia’s academic world. Lomonosov grew so exhausted by the constant quarrels that he appealed directly to the empress, asking Elizabeth to free him and the other academics from “Teplov’s yoke”. But Teplov’s connections at court were stronger, and the complaint went nowhere, and his colleagues had to put up with the situation. Over time, the fiercest clashes did subside somewhat, although resentment toward Teplov remained.

Teplov’s Service in Little Russia (Malorossiya)

The Razumovsky family came from a Cossack background. In 1750, Empress Elizabeth appointed Kirill Razumovsky as hetman in Malorossiya. A hetman was the head of the Cossack administration and the Cossack army in the region. In the Russian Empire at the time, “Malorossiya” (“Little Russia”) was the official term for the lands of what is now Left-Bank Ukraine — roughly, the territory east of the Dnipro, including the areas around Kyiv and Chernihiv.

Grigory Teplov went with Kirill into service in Malorossiya. He took up a key post in Razumovsky’s chancellery. Every administrative paper and decree passed through Teplov’s hands. That effectively made him the second most powerful person in Malorossiya after Razumovsky — because whoever controls documents and decisions controls the machinery of government.

Teplov left an ambivalent legacy in Malorossiya’s administration. On the one hand, bribery spread under him. He also planned to impose serf status on local peasants.

On the other hand, he planned to found Malorossiya’s first university in Baturyn (today in Ukraine’s Chernihiv region) and collected information on local history. These materials later became one of the early works on Ukrainian history, which is why Teplov is sometimes counted among the early founders of Ukrainian historiography.

Teplov’s Wives

Grigory Teplov married twice. His first wife was a Swedish woman; she bore him two children. She died in 1752. The cause of death is unknown.

Two years later, Teplov married again — Matryona Gerasimovna, a niece of Kirill Razumovsky. Formally, it was an official marriage, but their relationship was open.

Teplov knew that Matryona had an affair with the heir to the throne, Peter Fyodorovich — the future Emperor Peter III. The romance, however, did not last long. Peter was constantly away on business, and Matryona began writing to him often. Their correspondence started with a long, four-page letter in which she demanded that her beloved reply with an equally long letter.

Peter disliked writing, so this irritated him, and he decided to cut off contact with her.

Teplov’s Role in Catherine the Great’s Rise to Power

After Peter III came to the throne in 1762, Teplov’s career briefly collapsed. He was arrested for “careless words” — that is how the case file phrases it. Soon, however, he was released.

Teplov developed a deep hatred for Peter III and soon joined the plot against the emperor. The plot succeeded: Peter III was removed from power and soon “suddenly” died, and Catherine became empress.

Teplov, as one of the most educated participants in the conspiracy, was given an important task: to draft Peter’s abdication and to write the manifesto announcing Catherine the Great’s accession.

“Recognized by all as the most deceitful fraudster of an entire state; yet very clever, ingratiating, greedy, flexible — ready to be used for any business for money.”

— the Austrian ambassador, Count Mercy d’Argenteau

Taking part in the plot brought Teplov to the peak of his career. He was appointed to several high government posts, regularly dined with Catherine the Great, and developed reforms for her.

But already in 1763 his position became shaky again: a loud, scandalous case was opened against him for sodomy.

The Case of Sodomy Involving Enserfed Peasants

Nine serfs brought accusations against their owner, Grigory Teplov, saying that for six years he had forcibly compelled them “to commit sodomy on him”. The peasants endured the abuse for a long time, until they finally decided to unite and file a collective complaint.

Their petition was addressed to the Empress’s office that handled complaints and petitions, headed by Ivan Yelagin. After reading it, Yelagin promised to bring the matter to Catherine the Great’s attention — but in practice he preferred to bury it, apparently hoping to avoid a scandal around an influential official. For a long time it seemed no one would ever learn about these events, until word of the violence reached Teplov’s wife.

Matryona, Teplov’s wife, received a copy of the petition from a relative of one of the victims. She was shocked — “in considerable grief and crying” — but then summoned one of the serfs to ask whether it was true. Before long, everything also became known to Kirill Razumovsky, although he was probably aware of what was happening already.

Teplov himself, hearing about the complaint, decided to speak to each serf personally, inviting them in one by one to his bedroom. He tried to talk them out of taking things further, explaining that his status — as an influential official and someone close to the Empress — would allow him to avoid punishment.

He also reminded them that those who filed the complaint could face reprisals, because serfs had almost no rights, and investigators and courts usually believed the “master”, not the “servant”. Teplov did not so much threaten them as “warn” them, trying to calm things down so the scandal would not spread.

“… how did you dare to submit a petition about me to Yelagin? You know THE EMPRESS favours me, and I am a useful man, and THE EMPRESS will not want to lose one of her people — and people will always be more likely to believe me than servants. […] And as soon as they take you in for questioning, they will start torturing you; but even if they ask me anything, I will only say that you accused me for nothing — and then they will torture you to death.”

— Grigory Teplov, as relayed by the peasants from their interrogation in the sodomy case

Realising that an investigation was becoming inevitable, Teplov tried to push the serfs into giving false testimony. He offered them a version of events: they should say that in fact they had seen him with some “girl”, and that they had accused him by mistake of something that never happened. The point of this scheme was to shift the case from a serious accusation of sexual violence to a charge of “false denunciation”. Teplov assured them that in that scenario they would be punished comparatively lightly — for example, simply flogged. On top of that, he promised “as a sign of goodwill” to grant them freedom if any of them wanted to leave.

Outwardly, the peasants agreed and promised they would confirm the story about a woman. In reality, they did not abandon their plan: they secretly submitted a petition directly to Empress Catherine the Great.

The case was assigned to the Secret Expedition attached to the Senate.

The Investigation and the Testimonies of the Serfs

In the investigation files against Grigory Teplov, the investigators used the word skvernodeystvie (“an obscene act”) and the phrase “to do filth into the cheek”. This was the official bureaucratic wording used by the Senate’s Secret Investigation Office (the Taynaya Ekspeditsiya) for oral sex.

The first testimony describing violence came from the serf Vlas Kocheyev. He had previously belonged to Kirill Razumovsky, and after coming of age he was transferred to Teplov as a kamerdiner — a valet. (Kamerdiner is a word of German origin and literally means “room servant”: such a person took care of the master’s day-to-day needs, looked after his wardrobe, helped with shaving and bathing, and accompanied him on trips.) Kocheyev managed to marry, but the fact of marriage did not protect him from coercion by Teplov. During interrogation, Kocheyev described what happened in detail:

“Teplov kept him decently, but in that year, when he was already 20 years old, in the summertime, […] he slept with Teplov in the bedroom. Calling him to his bed, first caressing him and holding out the promise of rewards, and in the end also threatening him with beatings, he forced him to commit sodomy upon him. […] And besides that, Teplov made him do such filth ‘into the cheek’, which he was compelled to do too, for fear of beatings, and for that Teplov rewarded him, Kocheyev, with money and clothes.”

— from the case file “On the Active State Councillor Grigory Teplov, accused by his serfs of sodomy”

Teplov, according to the peasants, strictly forbade anyone to speak about what was happening — especially to priests: sodomy was considered a spiritual sin. Kocheyev was religious and feared that kind of punishment, so one day he decided to confess in a church in Little Russia. After the confession, the priest imposed an epitimia — a church penance — in the form of a ban on attending church for 300 days. Judging by Kocheyev’s later actions, he did not consider one confession enough, and later he sought forgiveness from a priest in Moscow. The city priest, already accustomed to such confessions, was less shocked and did not react in any way to the serf’s admission.

“[…] there is no sin in that, and it’s foolish priests who invented it for their own profit — and if you say anything, they won’t believe you, and I will say that you’ve gone rabid or lost your mind.”

— Grigory Teplov, as reported by the peasants in interrogation in the sodomy case

The testimonies of the other serfs who said they were harmed look almost identical. The Secret Expedition wrote up the materials in standard bureaucratic language and did not record the violent acts themselves in detail, focusing instead on what mattered formally: whether the sodomy happened on fasting days, and who knew about it.

In addition, according to the serfs, Teplov followed a repeating script: he started with nitpicking, then moved on to threats of beatings, and got obedience — sometimes reinforcing the coercion with gifts.

Finally, before filing their complaint, the peasants exchanged written notes so their stories would match and read as consistent. (All of Teplov’s serfs could read and write.)

At the same time, differences in the specific episodes show that Teplov could adjust his pressure tactics to the person. For example, he left a 17-year-old footman, Alexei Semyonov, alone after Semyonov said that he had confessed in a Moscow church. This does not mean Teplov “feared priests” as authorities — but the mere news of a confession, judging by Teplov’s behaviour, had an effect on him.

The next person named as harmed was 22-year-old Alexey Yanov, who served as a butler in Count Razumovsky’s household. After the assault, Teplov warned Yanov that if Yanov went to confession, it would be Yanov who would be sent to a monastery, while Teplov would suffer “no shame at all”. Despite the threat, Yanov still went to a Moscow priest, but “that priest told him to drop it as much as possible”.

The fourth testimony was from 24-year-old Ivan Tikhanovich, a native of Little Russia. Teplov raped him in a bedroom in Razumovsky’s St Petersburg house. To push Ivan into obedience, Teplov assured him that in the count’s household such things were “normal”, hinting that it was practically a tradition.

“And you, being a young man, can repent to the Lord God in your mind, and this is the same as debauching a girl, only among men — and in Count Kirill Grigoryevich’s house there are many singers and musicians, and where are they all to find girls for themselves, I think they debauch one another too — and it’s not only I who do this, others do it as well, only you keep silent about it.”

— Grigory Teplov, as reported by the peasants in interrogation in the sodomy case

The story of the fifth person, 19-year-old Vasily Lobanov, stands out for its demonstrative setting as described in the file: the coercion happened right at the table, when Lobanov was serving tea.

“… being […] in that Teplov’s house, he served him tea. Then, in private, Teplov, taking out his secret member, performed malakia [masturbation], […] and then Teplov made him do such filth ‘into the cheek’, and so, fearing beatings, he did it as well, and for that he rewarded him, Lobanov, with money and clothes …”.

— from the case file “On the Active State Councillor Grigory Teplov, accused by his serfs of sodomy”

Of the remaining four serfs, none could be interrogated — but the complaint was submitted on their behalf as well.

“I know better than priests myself what is a sin and what is not.”

— Grigory Teplov, as reported by the peasants in interrogation in the sodomy case

The end of the case turned out badly for the serfs, exactly as Teplov had predicted in advance. Catherine the Great issued a decree forbidding the victims, on pain of death, to tell anyone about what had happened. After that they were sent into exile: they were forcibly transferred into service with the Tobolsk Garrison Regiment in Siberia.

In principle, Teplov could have been punished for violence. But for same-sex contact as such there was no basis to try him under civilian law: at that time in Russia, direct criminal punishment for such acts existed only within the army. In theory, the church could also punish him — for example, by imposing an epitimia. In practice, however, the church in the empire depended on the state and could not act freely against a high-ranking official unless state power supported such a punishment.

As a result, Teplov suffered no punishment at all. More than that — a few years later he was promoted to Privy Councillor and awarded new orders. Over time he repaired his relationship with his wife, and she bore him three children.

This case shows how rightless serfs were in the Russian Empire: even under “enlightened” rule, real mechanisms for protecting rights worked only in the interests of the aristocracy and the nobility. Serfs were seen first and foremost as labour and as their owner’s property — and in their legal status, they could be closer to furniture than to people.

Teplov’s Life After the Investigation

In the years that followed the episode with the serfs’ complaint, Grigory Nikolayevich Teplov began building his inner circle not out of serfs, but out of young noble secretaries — among them, gay men.

In his memoirs, Giacomo Casanova mentions one of Teplov’s lovers — a young lieutenant from the Lunins. Casanova describes him as so handsome that he himself almost “gave in to temptation”. Casanova does not give this Lunin’s first name. We know the Lunin family had five brothers, so it could have been Ivan, Nikolai, or Alexander.

“… I found the travelling couple there, as well as two of the Lunin brothers. […] The younger was a pretty blond with an entirely girlish appearance. He was among the favourites of Teplov, the cabinet secretary, and being a resolute fellow, he not only placed himself above all prejudices but did not hesitate to take pride in the fact that with his caresses he could enthral every man he kept company with. […] Not suspecting such tastes in me, he decided to embarrass me. With that in mind, he sat down beside me at table and pestered me so persistently throughout dinner that I honestly took him for a girl in disguise. After dinner, sitting by the fire beside him and a daring Frenchwoman, I told him of my suspicions. Lunin, who prized his belonging to the stronger sex, immediately displayed convincing proof of my mistake. Wanting to see whether I could remain indifferent at the sight of such perfection, he moved closer and, once he was sure he had delighted me, took up the position necessary — as he said — for our mutual bliss. I confess, to my shame, that sin would have happened if not for [the Frenchwoman].”

— Giacomo Casanova

When the scandal around the serfs’ complaint died down, Teplov continued his career in the highest ranks of government service. He prepared a large number of reports for Empress Catherine the Great on how to reform administration and the economy.

Beyond that, he worked on establishing secondary schools (gymnasiums), funded orphanages, and was among the first to introduce tobacco brought from the Americas into agriculture — teaching peasants how to grow it.

“Teplov — immoral, bold, intelligent, deft, able to speak and write well.”

— the Russian historian Sergey Mikhaylovich Solovyov

Grigory Nikolayevich Teplov died in 1779, at the age of 68, of a fever. He was buried at the Alexander Nevsky Lavra monastery in Saint Petersburg.

Teplov’s Legacy

Like many educated people of the 18th century, Teplov was an “encyclopedist” — a polymath with broad interests, active in several fields of knowledge and creativity at once.

First, Teplov is known as an artist — as mentioned above. Second, he proved himself as a musician and compiled the first collection of Russian romances (urban art songs), titled Mezhdu delom bezdel’ye — roughly, “Idleness Between Tasks”. The songs are steeped in melancholy and focus on themes of unrequited love, betrayal, and suffering — plots that fit the era’s fashion for “sensitive” culture. You can still listen to these romances today.

▶️ Grigory Teplov — “V otradu grusti” (A Solace in Sadness), romance (YouTube)

“Not only did he sing himself in a fine Italian manner, but he also played the violin very well.”

— Jakob Stählin, academician and director of court fireworks

Third, Teplov is known as a philosopher and translator. He translated into Russian the works of the German thinker Christian Wolff. Teplov also wrote philosophical texts of his own. The best-known is Instruction to a Son, where he gives life advice and reflects on morality, kindness, and generosity. In this work, he tried to instil moral values — even if he did not always live by them himself.

“Love, or amorous passion, is the most pleasant and the most mad of passions. […] Though love is blind, it always dwells in the eyes, and even the proudest hearts submit to it. Everything that lives with a soul owes its very existence to it. It has no regard for sex, nor for age.”

— Grigory Teplov, from “Instruction to a Son”

🇷🇺 This piece is part of the article series “LGBT History of Russia”:

- Homosexuality in Ancient and Medieval Russia

- A Cross-Dressing Epic Hero: the Russian Folk Epic of Mikhaylo Potyk, Where He Disguises Himself as a Woman

- The Homosexuality of Russian Tsars: Vasily III and Ivan IV “the Terrible

- Uncensored Russian Folklore: Highlights from Afanasyev’s “Russian Secret Tales

- Homosexuality in the 18th-Century Russian Empire — Europe-Imported Homophobic Laws and How They Were Enforced

- Peter the Great’s Sexuality: Wives, Mistresses, Men, and His Connection to Menshikov

- Russian Empress Anna Leopoldovna and the Maid of Honour Juliana: Possibly the First Documented Lesbian Relationship in Russian History

- Grigory Teplov and the Sodomy Case in 18th-Century Russia

- Russian Poet Ivan Dmitriev, Boy Favourites, and Same-Sex Desire His the Fables ‘The Two Doves’ and ‘The Two Friends’

- The Diary of the Moscow Bisexual Merchant Pyotr Medvedev in the 1860s

- Maslenitsa Effigy: The “Man in Women’s Clothes” of Russia’s Pre-Lent Carnival

- Sergei Romanov: A Homosexual Member of the Imperial Family

- Andrey Avinoff: A Russian Émigré Artist, Gay Man, and Scientist

📣 Subscribe to our Telegram channel (in Russian): Urania. With Telegram Premium, you can translate posts in-app. Without it, many posts link to our website, where you can switch languages — most new articles are published in multiple languages from the start.

References and Sources

- РГАДА. Ф. 7, оп. 2, ед. хр. 2126. [RGADA – Russian State Archive of Ancient Documents, Fond 7, Inventory 2, File 2126]

- Кочеткова Н. Д. Теплов Григорий Николаевич // Словарь русских писателей XVIII века, вып. 3. [Kochetkova N. D. – Teplov Grigory Nikolaevich]

- Теплов Г. Н. Наставление сыну. 1768. [Teplov G. N. – Instruction to a Son]

- Гусев Д. В. «Обманка» Г. Н. Теплова и неизвестные факты его биографии. [Gusev D. V. – “Decoy” by G. N. Teplov and Unknown Facts of His Biography]

- Лаврентьев А. В. К биографии «живописца» Г. Н. Теплова. [Lavrentiev A. V. – On the Biography of the “Painter” G. N. Teplov]

- Смирнов А. В. Григорий Николаевич Теплов – живописец и музыкант. [Smirnov A. V. – Grigory Nikolaevich Teplov as Painter and Musician]

- Теплов Г. Н. // Русский биографический словарь, в 25 т. [Teplov G. N. – Russian Biographical Dictionary]

- Осокин М. «Между делом сквернодействия» Григория Теплова. [Osokin M. – “Between Deeds of Debauchery” of Grigory Teplov]

- Alexander J. T. Review of Catherine the Great: Art, Sex, Politics by Herbert T.

- Tags:

- Russia

- Queerography