Andrey Avinoff: A Russian Émigré Artist, Gay Man, and Scientist

How Orthodox Christianity, butterflies, a scientific career, and male eroticism came together.

- Editorial team

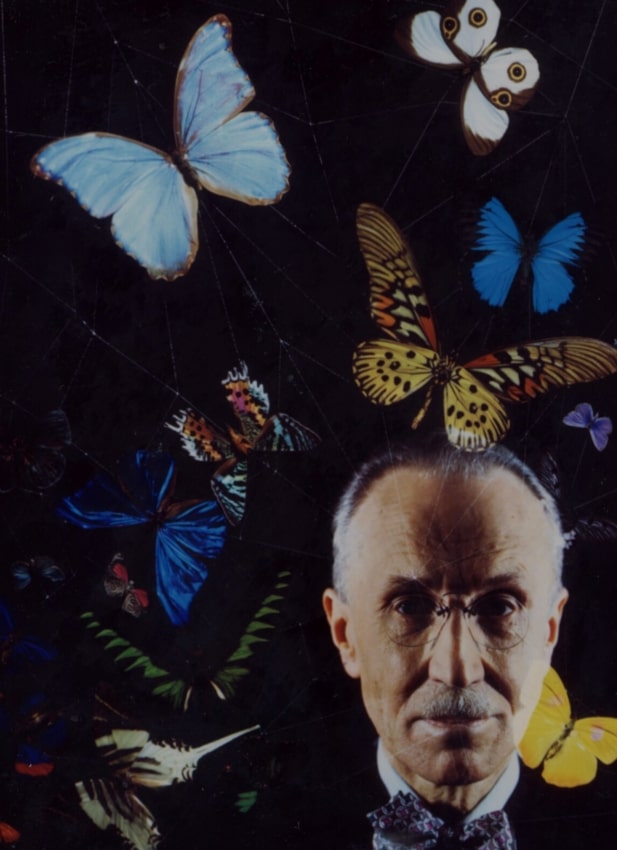

Andrey Avinoff was a Russian entomologist and artist, and a friend of Alfred Kinsey. He was a collector, a connoisseur of beauty, and a gay man, yet he never made his sexuality public. After the Revolution in 1917, Avinoff left Russia for the United States. His homoerotic watercolors were published only in the 21st century.

A posthumous exhibition of his paintings in Pittsburgh in 1953 made no mention of this side of his life. In the homophobic United States of that era, the organizers deliberately concealed Avinoff’s identity as a gay Russian artist.

That makes his legacy all the more significant - both the breadth of his interests and his complex, layered identity. Avinoff was a gay Russian artist and, at the same time, an Orthodox traditionalist who managed to achieve success in the intensely heteronormative world of American science and education.

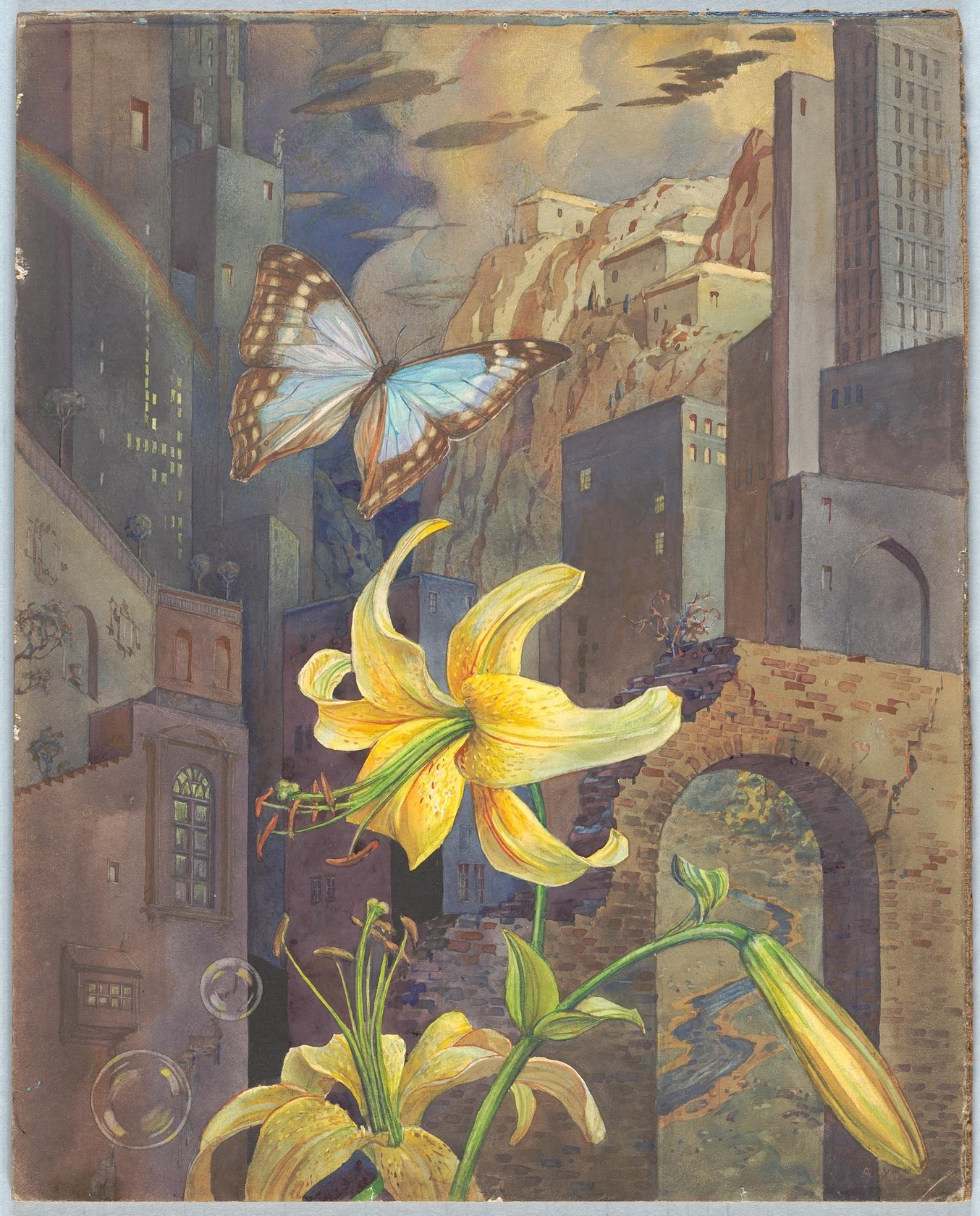

In this article, we will examine the biography of the Russian émigré and painter of butterflies, ballet, orchids, rainbows, soap bubbles, and beautiful young men.

Origins, Childhood, and Early Interests

Andrey Nikolaievich Avinoff was born in 1884 in Tulchyn (now in Ukraine) into an aristocratic family. Family acquaintances later remembered him as a child with an unusually developed command of language, long golden curls, and delicate facial features.

He grew up surrounded by noble relatives who traced their lineage to an ancient family of Novgorod boyars. His grandfather fought against Napoleon and rose to the rank of admiral, and his father was a lieutenant general. His older brother Nicholas (“Nika”) later became a committed liberal reformer, while his sister Elizaveta (Elizabeth) became a successful artist - she painted portraits of American millionaires and even Franklin Roosevelt.

“In a fine, elegant hand - his own calligraphy - he drew long charts, aligning his past with the period before the birth of Christ. He was absolutely certain that he was related to Cleopatra by indirect kinship…”

- Alex Shoumatoff, Andrey Avinoff’s grandnephew. Family Recollections

According to a family legend, at the age of five Andrey caught his first butterfly, and by seven he was already reading the books of the American entomologist William J. Holland. From then on, butterflies remained with him for the rest of his life.

Avinoff’s father was a gentle man - the children were loved, hardly forbidden anything, and encouraged in whatever passions they developed. He taught Elizaveta to embroider in cross-stitch. From him Andrey inherited a passion for collecting, a subtle sense of humor, and the habit of welcoming guests with attentive generosity.

In 1893, his father was appointed a commanding officer in Tashkent. Nine-year-old Andrey traveled there with his family via Vladikavkaz, Tbilisi, Baku, and the Caspian Sea. In Tashkent, the Avinoffs befriended the Kerensky family and escaped the heat in the Chimgan Mountains, living in a yurt.

“That summer they suffered terribly from the heat. My father remembers how, as a child, he heard his grandmother and grandfather sitting in barrels of water in Tashkent and playing cards.”

— Alex Shoumatoff, Andrey Avinoff’s grandnephew. Family Recollections

While collecting rare butterflies in Uzbekistan, Avinoff also painted them in watercolor. Because of congenital nearsightedness, he could discern the tiniest details of their anatomy without any instruments.

His mother could not endure the Tashkent heat - a year later, she returned to the family estate in Shideyevo, taking Andrey and his younger sister with her. Andrey settled in a church outbuilding. There, he flitted from one pursuit to another and quickly cluttered up the room - including with sunflower-seed shells, which he ate constantly. By then his collection had grown noticeably and kept expanding, including rare specimens.

He had a warm relationship with his younger sister, Elizaveta: he taught her to draw and always helped her. In the winter of 1905, Elizaveta sculpted a snow statue of Marie Antoinette in the garden, and Andrey, then 21, made Voltaire beside it. Their older brother Nicholas managed to photograph them, but at night the watchman smashed the “snowmen” with a shovel, mistaking them for burglars.

Education, Service, and Expeditions

In 1905, Avinoff graduated from Moscow University with a degree in law and took a position in the Senate as an assistant to the secretary general, where he reviewed the correspondence of suspected revolutionaries. In 1911, he was appointed chamberlain at the court of Nicholas II; within the Diplomatic Corps, he served as master of ceremonies. During his leaves, he devoted himself to butterflies.

An inheritance from his uncle enabled him to leave government service and organize two butterfly-collecting expeditions. The first took place in 1908. On the second, in 1912, he crossed the western slopes of the Himalayas - from India to Turkestan.

His best-known discovery in lepidopterology was a new butterfly species, which he named Parnassius autocrator (“the Autocrat Apollo”) for its majestic appearance.

Avinoff returned with a collection of 80,000 specimens, including around 90% of all butterfly species known at the time from Central Asia. In his Saint Petersburg apartment, cabinets filled with the collection were part of the interior. After the Revolution, the collection was confiscated by the communists and transferred to the Zoological Museum in Saint Petersburg.

In 1913, Avinoff presented the collection and his work at a meeting of the Entomological Society of London, speaking in impeccable English. He later wrote a series of books on Central Asian butterflies and received a gold medal from the Imperial Russian Geographical Society for them.

Two exhibitions of his work were held in Moscow alongside other artists. Avinoff showed both butterflies and mystical landscapes with a “Tibetan” mood; nearby hung abstractions by Malevich and Kandinsky. That same year, he met Sergei Diaghilev.

Before the First World War, he helped finance a further 42 expeditions of the same kind. By the age of 30, Avinoff had assembled one of Europe’s largest butterfly collections and published seven articles on his discoveries in three languages.

World War I and Emigration

With the outbreak of World War I, he was exempted from military service because of poor eyesight. He then worked for the Zemstvo Union - an equivalent of the Red Cross - and tended to the wounded in Łódź.

In 1915-1916, the Zemstvo Union sent him to New York to purchase ammunition and medical supplies. There, Avinoff attended a performance by Vaslav Nijinsky, met him backstage after the show, and later painted his portrait.

Avinoff spent 1916 and most of 1917 in Russia, but in September 1917 he was again dispatched to the United States. He traveled east along the recently completed Trans-Siberian Railway, via Japan, and disembarked in San Francisco. He used this trip as an opportunity to emigrate: formally, he arrived as a representative of the new Provisional Government, in which his brother Nicholas held a ministerial post.

That same winter, Avinoff’s sister Elizaveta left for the United States on one of the last trains - together with her husband, Leo Shoumatoff, and their family. Nicholas remained in Russia. In 1919, their estate was destroyed.

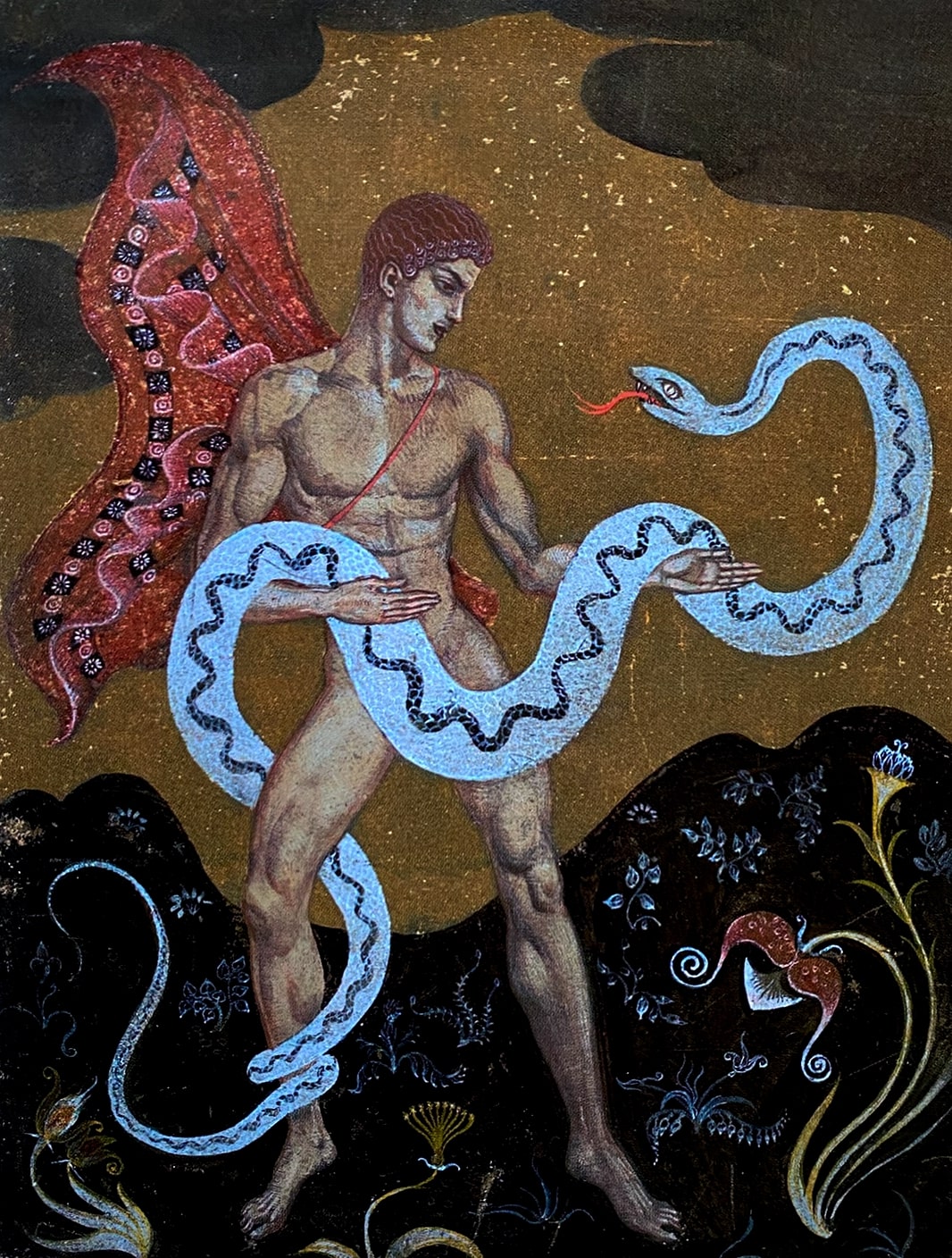

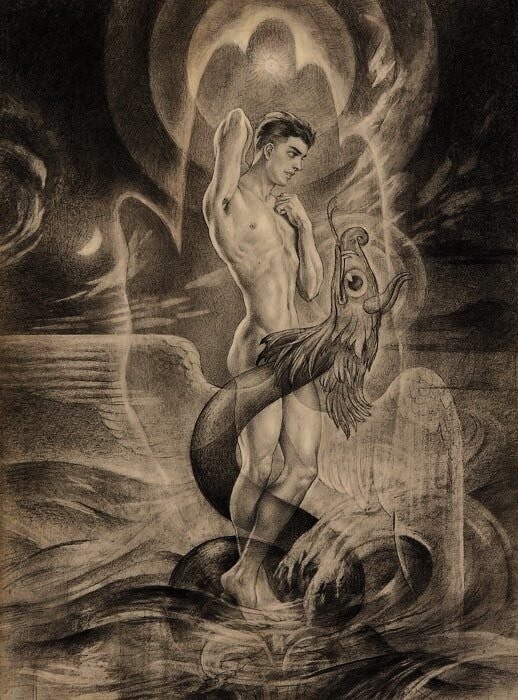

Avinoff managed to save only a few of his most cherished butterfly specimens, a bundle of watercolors from his second expedition, and several paintings, including Cretan Motif. It depicts a supple, muscular nude man grappling with a giant snake; his cloak, in silhouette, resembles the wing of an enormous butterfly. The mention of Crete as a “gay paradise” in fin-de-siècle (late-19th-century) imagination further reinforces this symbolism.

Early Years in the United States

After the end of the First World War, Andrey and Elizaveta found themselves in the United States: he was 33, and she was 29. With their remaining funds, they bought a dairy farm near New York City. The farm became a temporary refuge for new émigrés from Russia: a ground-floor room with four beds nearly turned into a dormitory. During the day, the newcomers worked in the vegetable garden; in the evenings, they gathered to talk.

The dairy business did not work out. Elizaveta began earning money by painting portraits. Her husband, Leo, worked for Sikorsky’s aircraft company and died in 1928 - he accidentally drowned.

Avinoff’s cultural inheritance, Orthodox faith, and homosexuality were as important to him as his love of butterflies and his artistic talent. Yet none of this fit easily into the scientific, Protestant, and capitalist values of his new country. As a result, expressions of his Russian identity had to be translated into forms that could function within an American environment.

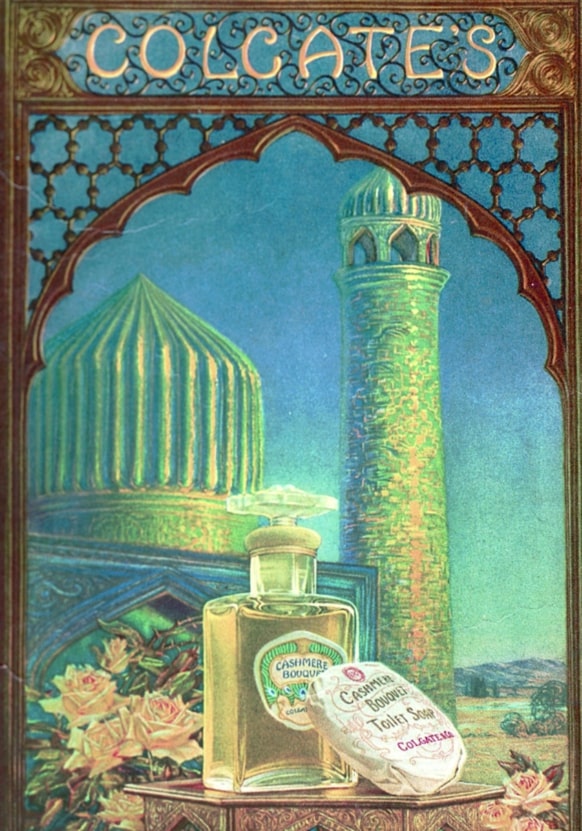

By that time, New York already valued Russian music and theater and was familiar with Russian artists, including Bakst, Anisfeld, and Roerich. Avinoff began to earn good money creating advertisements for American companies. He painted a bottle of Florient by Colgate against the backdrop of Himalayan snow-capped peaks - landscapes from his past - and won a prize at the Third Annual Exhibition of Advertising Art in 1924.

He held steady work with Johns-Manville, a manufacturer of asbestos roofing shingles and building materials, and had a brief affair with Chevrolet. In 1930, he designed the Winged-S logo for Sikorsky helicopters, which is still in use today.

“He is probably the only man who ever established - or tried to establish - a connection between butterflies and the Russian Revolution.”

— Geoffrey T. Hellman, The New Yorker, 1948

In 1921, Avinoff held his first notable art exhibition.

Return to Entomology and Museum Work

“At present, I have all but abandoned any hope of recovering this collection [of butterflies], and I have neither the courage nor the means to start a new one.”

— Andrey Avinoff

At first, trying to survive and earn a living, Avinoff devoted little time to butterflies. His colleague Charles Oberthür, a French specialist in hawk moths, persuaded him to begin collecting butterflies again, calling it a duty to science.

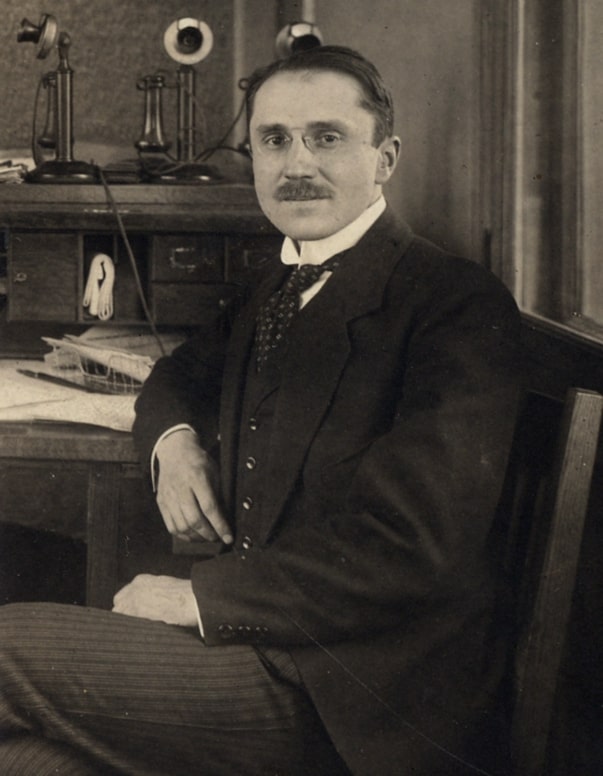

Avinoff’s reputation as an entomologist, together with his connections to the collector B. Preston Clark, worked in his favor - he was recommended for a post in the entomology department of the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh. In 1922, he met William J. Holland, whose books he had read as a child. Holland headed the museum and the university. At the time, Carnegie generously funded efforts to broaden the horizons of Pittsburgh’s youth - archaeological excavations, scientific research, and the acquisition of fossil and insect specimens for the museum.

Holland took a liking to Avinoff and offered him a job as assistant curator of the entomology department. Avinoff accepted. In 1923, he worked on sorting the museum’s collection and identified 23 new butterfly species.

In gratitude, Holland named the butterfly Erebia avinoffi after Avinoff, and Thanaos avinoffi after his grandfather, an admiral.

“His art was the art of high culture, as it was in Russia.”

— John Walker, Director of the National Gallery of Art

Holland soon retired. The next museum director served briefly and died in 1926. After that, Avinoff was invited to take the role - he accepted and became the museum’s new director, remaining in the post for the next 20 years. One of his achievements was acquiring a complete Tyrannosaurus skeleton.

In 1927, Avinoff received an honorary Doctor of Science degree from the University of Pittsburgh, and in 1928 he became a U.S. citizen. At the university, he lectured in the departments of fine arts and biology. There, he personally designed the “Russian Room” - one of the Nationality Rooms, teaching classrooms that recreated traditional ethnic interiors.

The mass confiscations of church and aristocratic property launched by the Bolshevik government sparked a wave of Russian export sales in Europe and the United States in the 1920s and 1930s. Avinoff bought books at these sales and assembled a major collection of Russian publications on art, architecture, culture, and history. Today, the collection is housed in the library of Hillwood Estate. It includes rare small-print editions and at least one uniquely preserved item - a facsimile of an illustrated medieval Apocalypse.

“For a time I saw Dr. Avinoff at meetings and so on. I must say that he made a profound impression on me. […] I have never met anyone with such universal knowledge as he had. At every party I tried to figure him out, but I never could, because he really knew everything. Each time he would come out with an extraordinarily learned fact, or something you did not expect. He always did it respectfully, almost as if apologizing for his sharpness. It was very curious. Perhaps it is a Russian trait.”

- John Walker, Director of the National Gallery of Art (U.S.)

From 1925 to 1940, Andrey Avinoff traveled to Jamaica six times and collected around 14,000 butterflies. He bought a Chevrolet - he wanted to “become an American” and drive around the island - but he never learned to drive: his nephew took the wheel. Avinoff’s Jamaican collection can be seen at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

In the early 1930s, he reached an agreement with the Soviet authorities to catalog his Russian collection, which had been nationalized after the Revolution. Shipments of insects were sent to him from Leningrad; he studied them while also acquiring comparable specimens and entire collections for Pittsburgh.

During this period, his brother Nicholas, after his seventh - and final - arrest in November 1937, disappeared during the Stalinist purges. A cousin died in a penal colony on the Yenisei in 1942.

In academia, Avinoff taught scientific illustration and biology at the University of Pittsburgh, served on the board of the American Association of Museums, chaired the League of Nations Committee on Scientific Museums, was elected a Fellow of the Entomological Society of America, and was appointed a trustee of the American Museum of Natural History. From 1937 until his death, Avinoff corresponded with Vladimir Nabokov and almost certainly advised and assisted him in his scholarly work at Harvard University.

Outside his primary post, Avinoff lectured on art history. He joined the committee responsible for staging avant-garde projects for the League of Composers in New York, served on the board of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, worked on behalf of the Ballet Society of America in New York, and held solo exhibitions of his work.

Around 1935, his friend George Hann - a wealthy man and a pioneer of commercial air transport in the United States - acquired a major collection of Russian icons. For nearly four decades, the Hann collection was regarded as one of the finest groups of icons outside the Soviet Union, and Avinoff became the leading authority on icons in the United States. In July 1943, President Roosevelt thanked Avinoff for information about icons presented to him by U.S. ambassadors to the Soviet Union.

After Hann’s death, the collection was dispersed at auction, but the Soviet émigré restorer Vladimir Teteriatnikov declared almost all of it to be modern forgeries and copies. This struck a blow to the international market for Russian icons - and to Avinoff’s reputation as an expert. At the same time, Teteriatnikov noted that Avinoff was a capable specialist but made mistakes because he relied on comparisons with book illustrations, mostly from editions published before 1900 - and those publications did not reflect the 20th-century icon industry.

Avinoff’s hopes for collaboration among museums worldwide, including Soviet institutions, collapsed with the outbreak of World War II. He was also among the prominent signatories of a protest statement against the Soviet invasion of Finland on November 30, 1939.

“I consider Avinoff one of the greatest people in the world. He and his sister arrived in this country with nothing and became two of its most outstanding citizens. I am proud of America because this happened. And I am proud of them.”

- Archibald Roosevelt, son of President Theodore Roosevelt and a friend of the Avinoffs

Later Years: New York, Intensive Painting, and Death

In 1945, after a heart attack, Avinoff retired from the museum and moved into his sister’s mansion in Locust Valley on Long Island. In 1948, he persuaded his sister to relocate with him to Manhattan - they rented neighboring luxury apartments on Fifth Avenue.

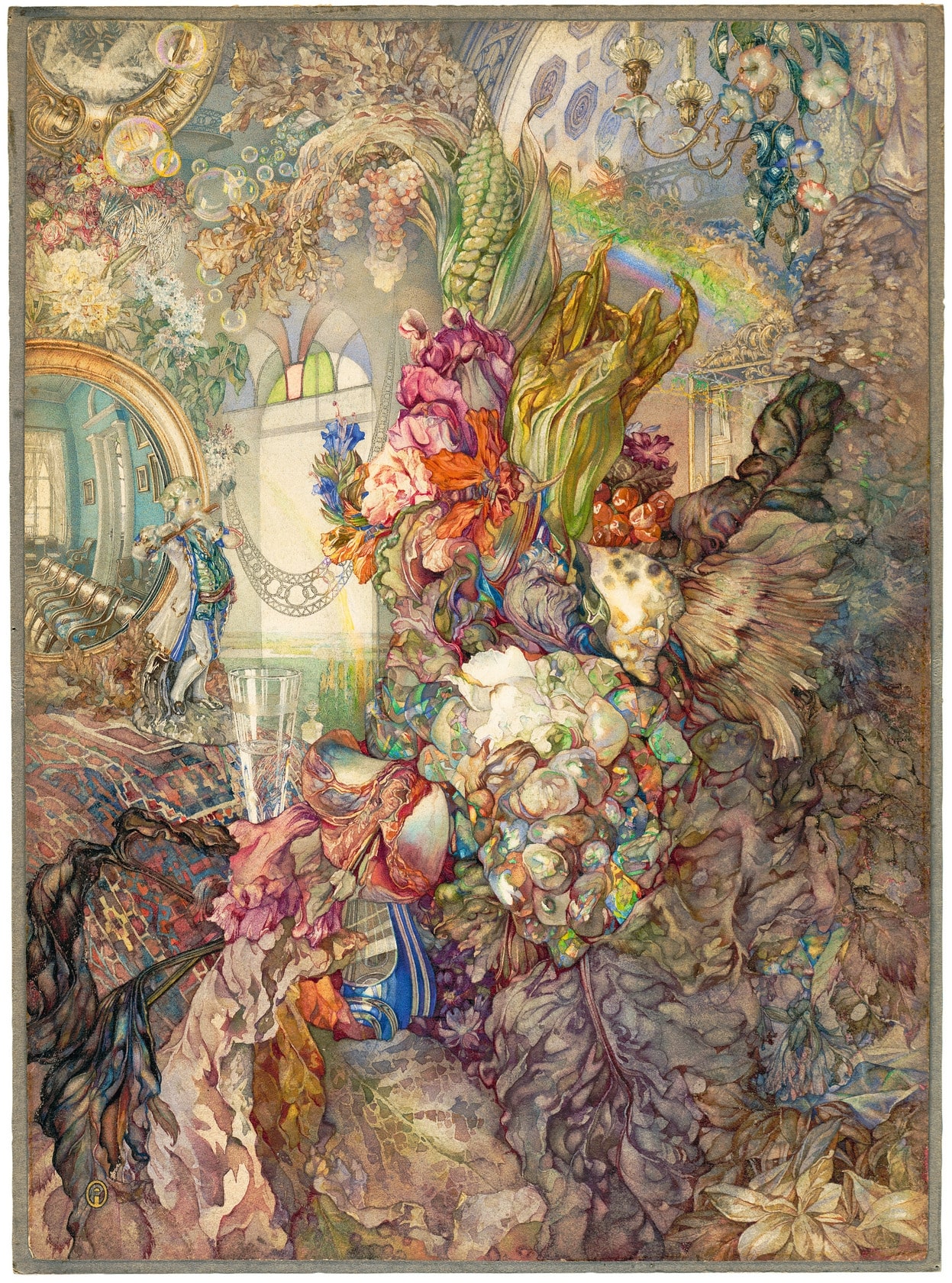

In New York, he devoted himself to painting full-time. He produced still lifes, surrealist landscapes, and botanical illustrations. Over four years, despite frail health, he created more than 200 compositions and became the subject of 11 solo exhibitions. Life magazine planned to feature him on the cover of its fall 1949 issue.

“The best way to understand the nature and soul of the Russian people is through a sympathetic study of their creative endeavors as expressed in painting, architecture, literature, and music.”

— Andrey Avinoff, “Introduction to an Exhibition of Russian Art,” 1943

By his own admission, Avinoff’s political views were right-wing. He was an antisemite - something remembered by some of his Jewish colleagues in Pittsburgh. In the Russian Empire, such views were widespread.

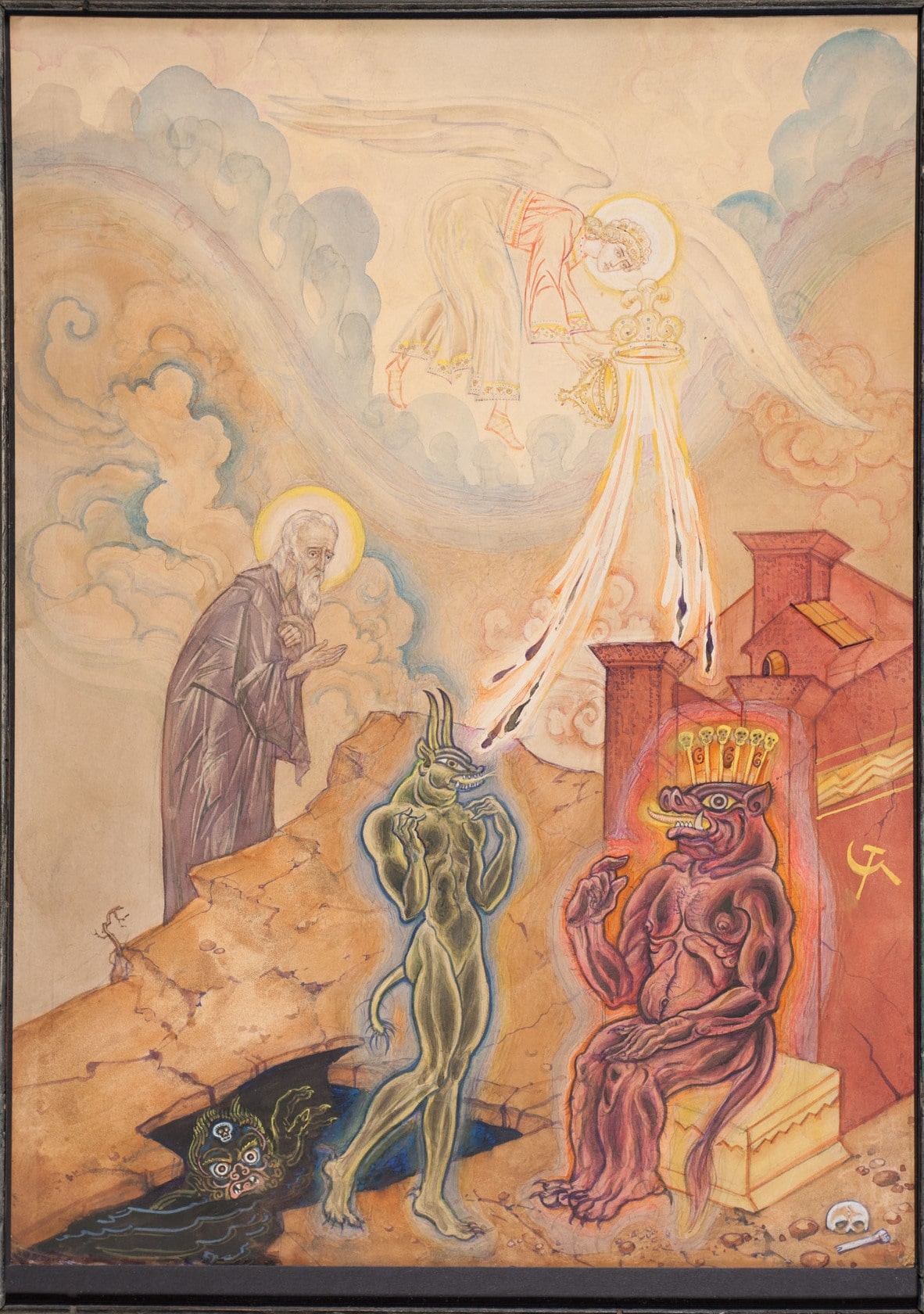

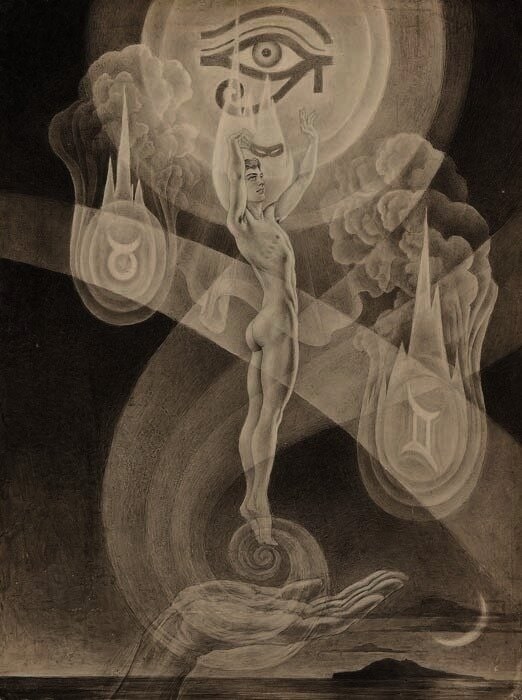

Avinoff was deeply religious. Throughout his life, he remained firmly committed to Russian Orthodoxy and acknowledged a mystical bent in himself - it shaped his highest ideals and led him toward themes laden with symbolism.

For all his outward traditionalism, in other respects he proved thoroughly modern. He readily embraced capitalism and democratic citizenship, and thanks to a cosmopolitan upbringing and his command of languages, he knew how to operate effectively in an American environment. Unlike many Russian émigrés, he took little part in futile campaigns to overthrow the Bolshevik or Soviet regimes. Instead, he tried to preserve and root in his new homeland the best that Russian culture could offer Western civilization.

Andrey Avinoff died on July 16, 1949. His last words were: “The air - how pure it is.” Two days later, he was buried in a Russian Orthodox church. The epitaph on his gravestone at Locust Valley Cemetery on Long Island reads: “BEAUTY WILL SAVE THE WORLD”.

“It seemed as if the scent of a rose came from the tip of my brush as I painted. I became the rose.”

- Andrey Avinoff

▶️ A Former Student’s Recollections of Avinoff (in English) (YouTube)

Homosexuality, Homoerotic Art, and Kinsey

A key figure in Avinoff’s sexual and intellectual evolution was the Viennese writer Otto Weininger. His book Geschlecht und Charakter (Sex and Character) was published in German in 1903 and, like Kuzmin’s Wings, became a scandalous bestseller. Andrey’s brother Nicholas was familiar with it - his wife Maria referred to Weininger and quoted his idea that every person possesses, to some degree, both male and female genes.

Avinoff, it seems, regularly visited Russian bathhouses and described to Kinsey bathhouses with private rooms and young masseurs aged 16-20 who were “always available” - one or two at a time - and who willingly attended to clients. He also idolized the ballet dancer Nijinsky.

In the United States, Avinoff had to adapt to a more homophobic cultural environment than in his native St. Petersburg. For instance, publishers rejected his cover sketch for the magazine The Machinist because it struck them as “too much of a display of male charms.”

At the Carnegie Museum, Director Holland was known for his homophobia. Another of Avinoff’s scientific patrons, B. Preston Clark, had endured the suicide of his gay son, who took his own life in 1930. In the 1930s-1940s, homophobia and intolerance in the United States intensified and were reflected in legislation.

Avinoff never flaunted his homosexuality and was forced to be extremely cautious. The Pittsburgh establishment knew him and accepted him as a lifelong bachelor. Only within a close circle of friends was his homosexuality treated as one facet of his charm - everyone knew, and no one was bothered by it.

“For him, art was a reflection of nature. Dr. Avinoff’s genius [encompasses] the full spectrum of human experience. […] Like the masters of the Renaissance, he was, in many ways, a consummate and outstanding scientist, artist, museum professional, mystic, and friend to many.”

— Walter Read Hovey, Chair of the Department of Fine Arts, University of Pittsburgh

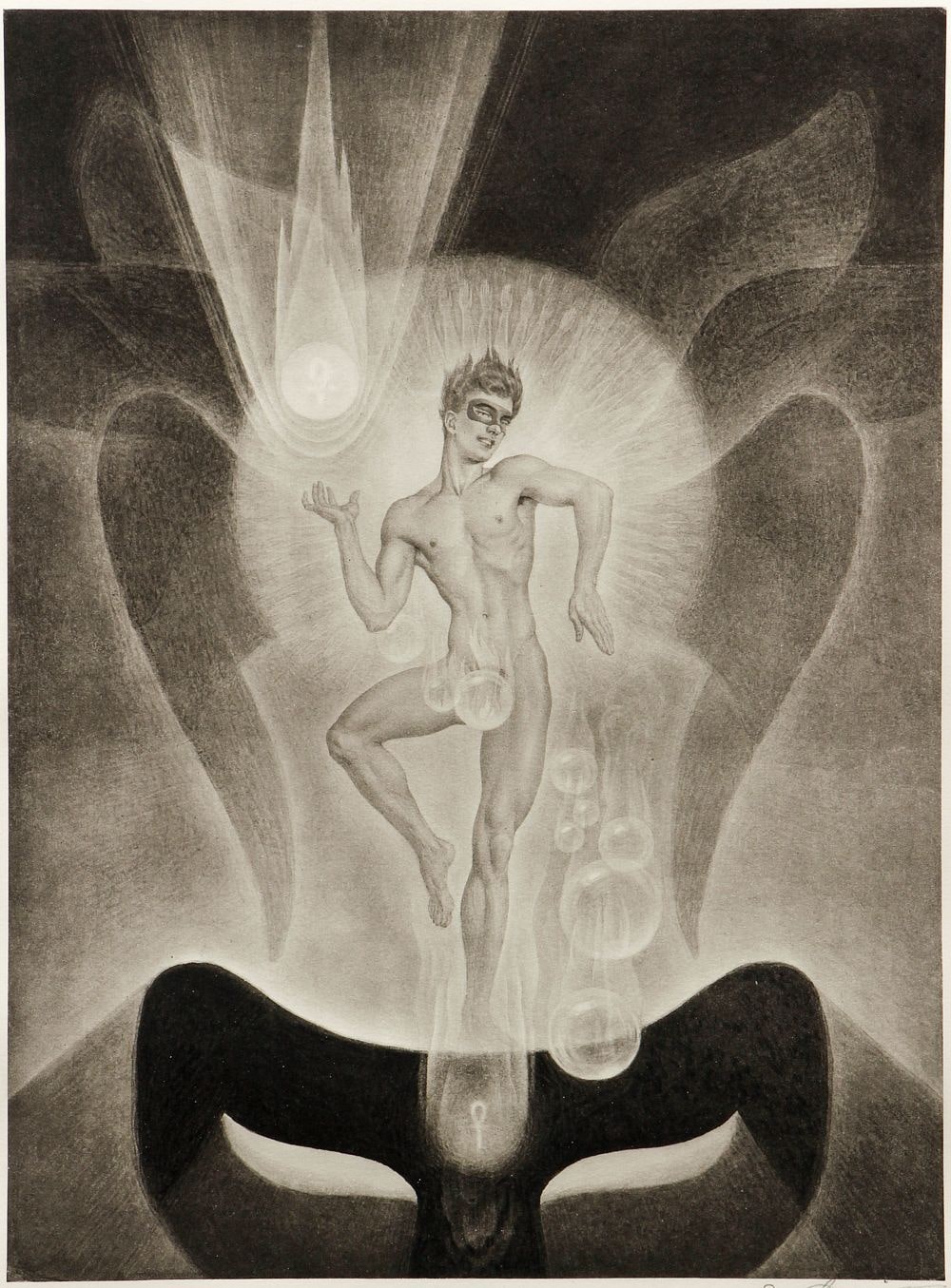

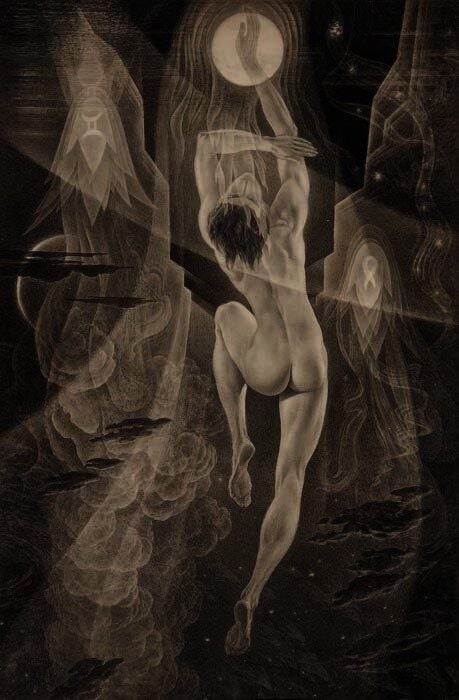

Avinoff led an active but discreet gay life and produced a substantial body of homoerotic art. In addition to butterflies and flowers, he depicted nude young men, angels, demons, and ghosts. After a heart attack in 1945, he destroyed most of these works - he “did not want to leave such things” to his sister. Later, he referred to what happened as his “holocaust.”

His romantic relationships, apparently, were unstable, unequal, and short-lived. In this, he may have resembled his older brother Nicholas - Nicholas’s wife complained that their life together could not compete with her husband’s “high calling.”

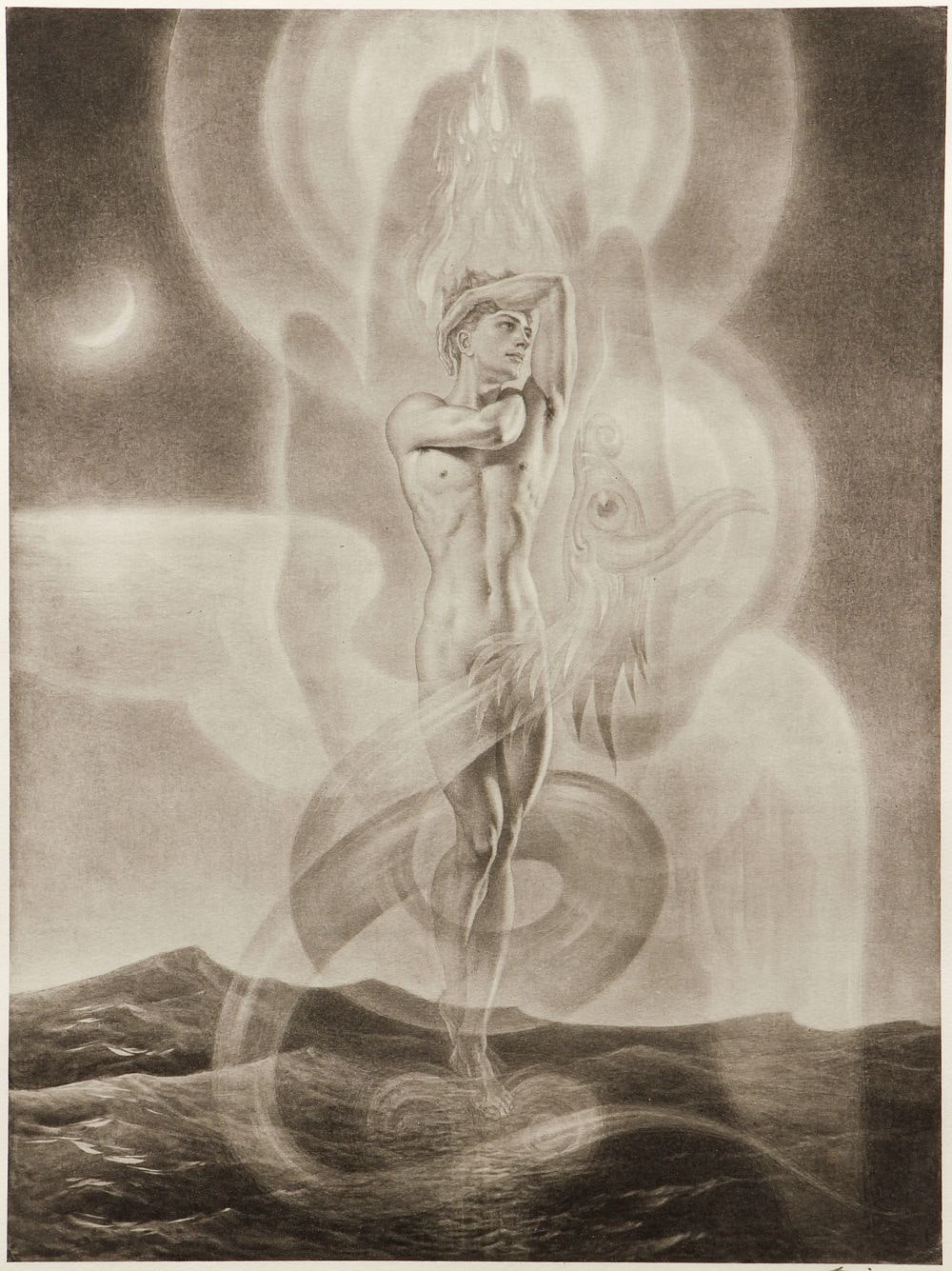

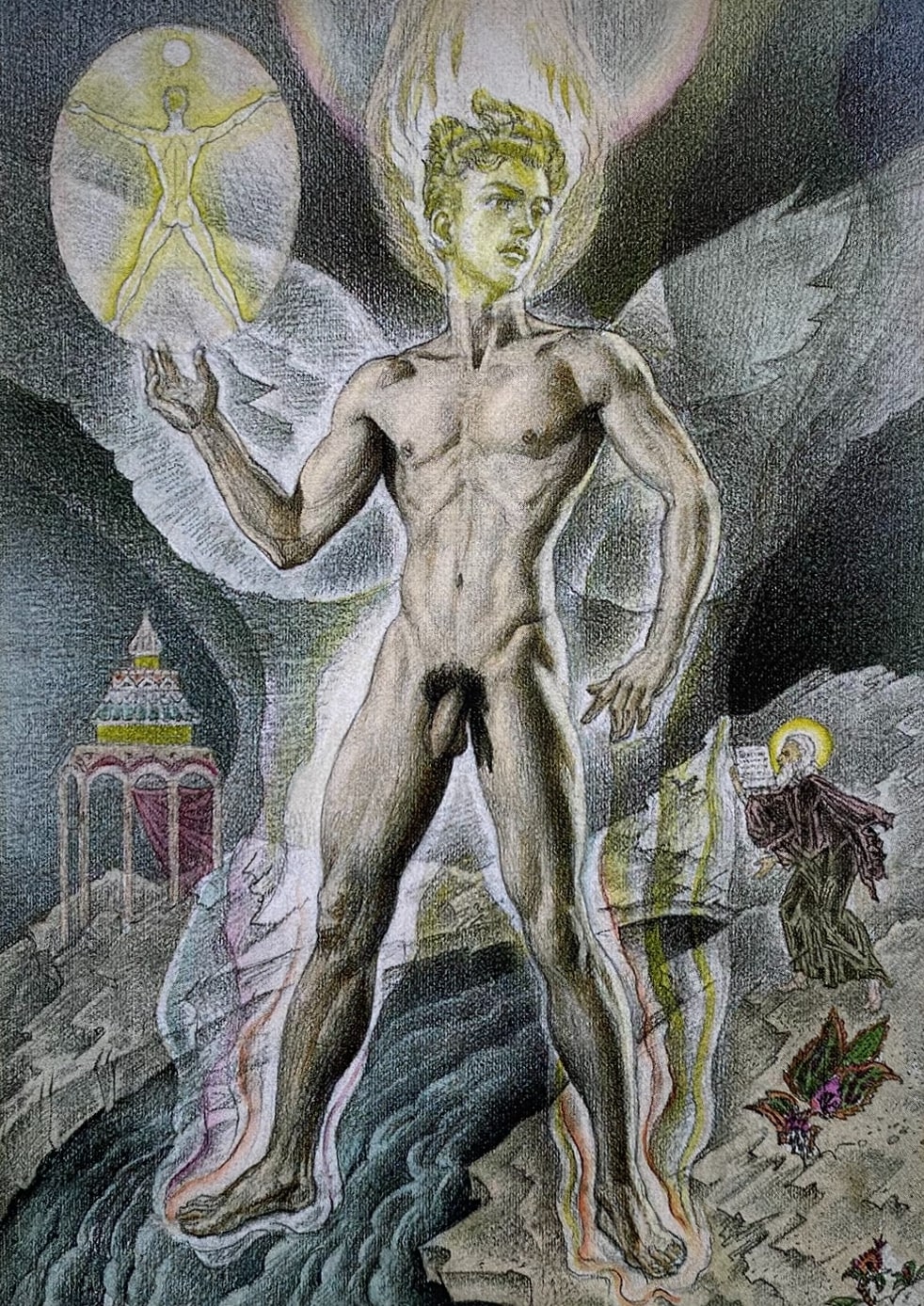

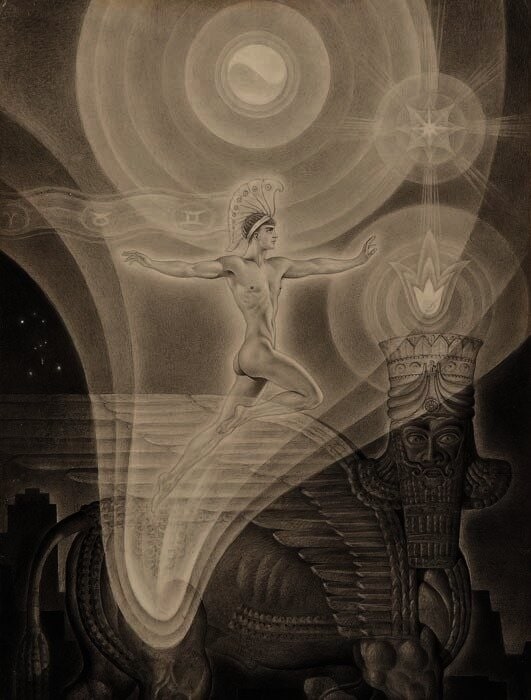

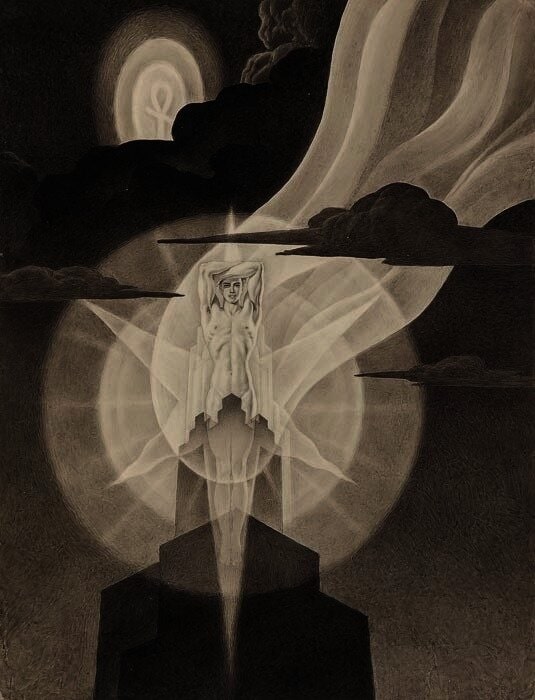

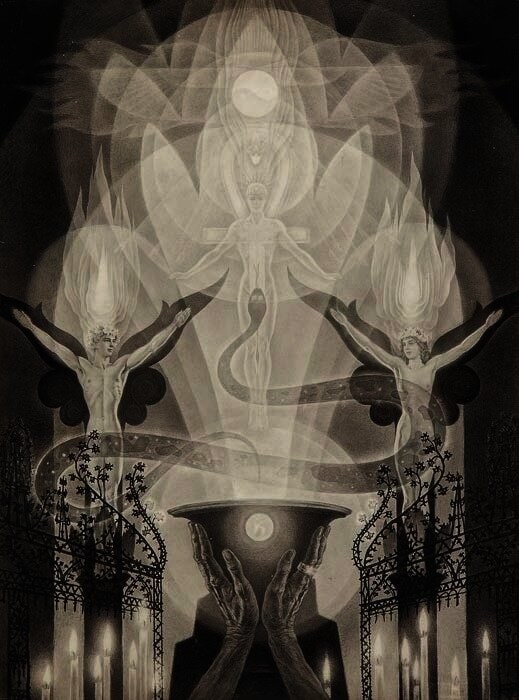

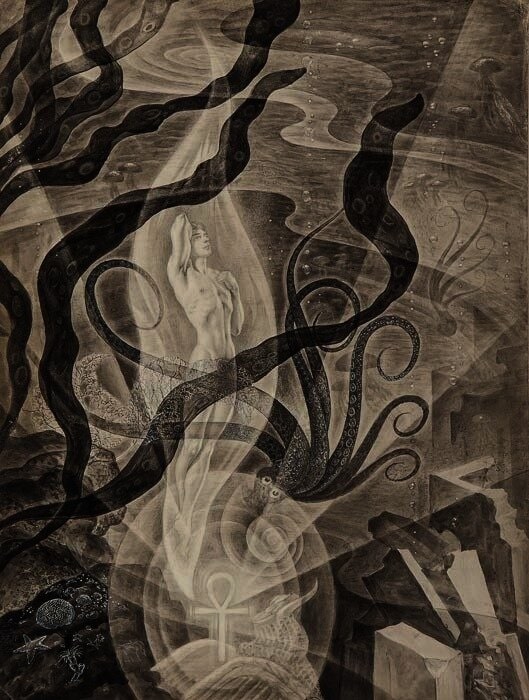

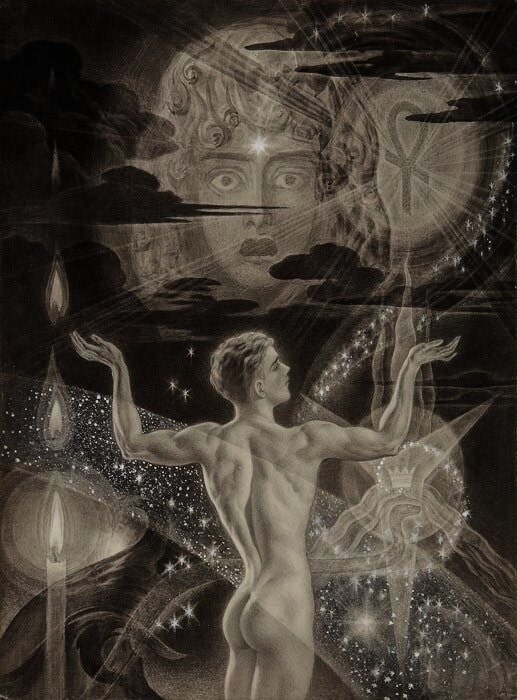

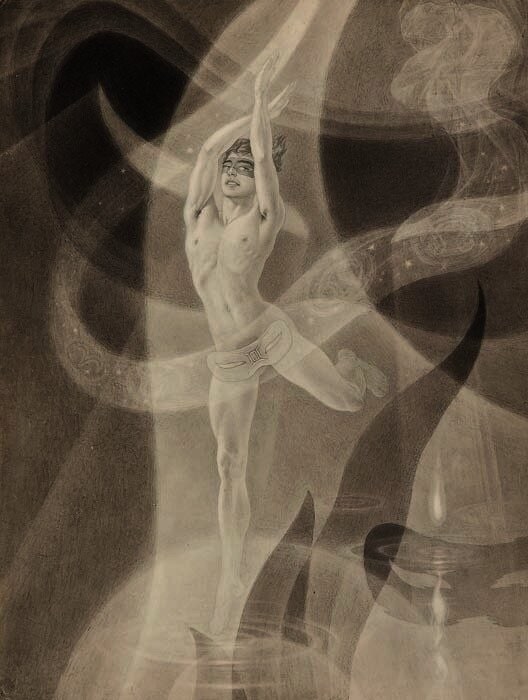

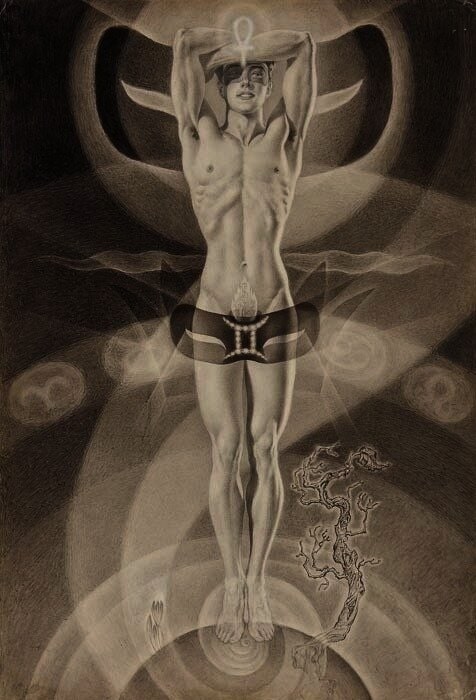

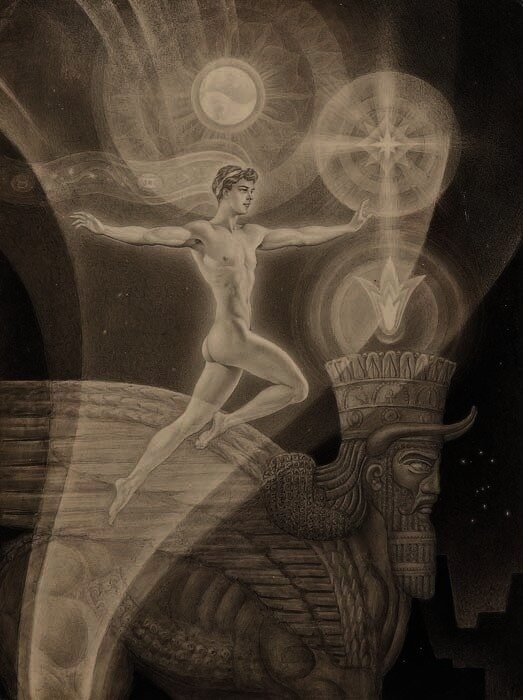

One of Avinoff’s best-known series of illustrations was created around 1935 - 1938 for The Fall of Atlantis (1938) - a long Russian-language poem published in the United States by George V. Golokhvastoff. In 1944, Avinoff issued these illustrations, originally executed in charcoal, chalk, brush, pen, spattering, and scratching on paper, as a separate limited-edition portfolio of photogravures.

Reproduced as photogravures, Avinoff’s drawings are symbolically multi-layered - meditations on the rise and fall of civilizations, spirituality, ambition, and desire. They are inhabited by magnificent winged male “spirits.”

An interest in sexuality led Avinoff to a friendship with Alfred Kinsey - a sex researcher who also studied butterflies. In January 1948, Kinsey published the groundbreaking study Sexual Behavior in the Human Male. Having learned in late 1947 that the book was forthcoming, Avinoff broke his long silence about his own homosexuality: he wrote the author a congratulatory letter and, in effect, came out.

“Allow me to introduce myself. I am a fellow entomologist… I read about your forthcoming book in the latest issue for ’47, and I am very interested to know when it will appear… My observations of the artistic and theatrical world of Old Russia - including poets and writers - have led me to wonder whether there may be certain parallels with conditions in this country. I hope you will excuse this letter from a stranger.”

- Andrey Avinoff. Letter to Alfred Kinsey. December 14, 1947

A close friendship developed between the two men. Avinoff became an active participant in the work of the newly established Institute for Sex Research. He supplied it with materials about his sexual biography, as well as samples of his own creative work.

Avinoff introduced Kinsey to New York’s milieu of gay artists, dancers, musicians, and designers. He also spoke of his dream “in time to create some sort of fund or scholarship” that could bring together kindred spirits - people with a similar emotional temperament and a shared aesthetic philosophy.

He put some of these plans in writing; the documents are held at the Kinsey Institute. Avinoff envisioned an elite male club with private rooms decorated with frescoes of beautiful young men, and he produced sketches for such frescoes - which also survive at the Kinsey Institute. In his conception, the organization was to consist of senior members whose mission was to identify and “initiate” promising young candidates. Avinoff called it “APOCATL”; the origin of the name is unknown.

They also planned a joint project on the relationship between creativity and sexuality, but Avinoff managed to complete only part of the work - more than 600 pieces - before he died in 1949.

“Fair-haired young men - who were Andre’s ideal of both spirituality and sexuality - recalled the biblical description of angels as beings both spiritual and beautiful.”

- Paul Gebhard, a Kinsey associate

In the 1930s - 1940s, Avinoff attended life-drawing classes at Carnegie Institute of Technology. Around the same time, Andy Warhol studied at these two institutions as well - he was born and raised in Pittsburgh in a family of Carpatho-Rusyn immigrants. Warhol began his career with drawings of butterflies and later became one of the first major American artists to openly declare his homosexuality.

In 2005, the Kinsey Institute mounted the exhibition “Beyond Russia: Chagall, Tchelitchew, Avinoff,” which displayed works from the institute’s collection and, for the first time, presented Avinoff’s erotic drawings.

Gallery

Impeccable manners, an aristocratic bearing, and self-deprecating humor in Andrey Avinoff went hand in hand with an enormous capacity for work. By professional label, he might easily be filed away as an illustrator, yet his illustrations were devoted to subjects he took with utmost seriousness - a mystical sense of the interconnectedness of nature, life, and spirit. In the same vein, an obsession with “super-achievement” blended with aesthetics in his work.

“Avinoff should rightly be regarded as one of the most important surviving artists of Russia’s Silver Age to have made it to the United States. He not only embodied the ideals and practices of the Silver Age in his life and work, but also passed them on to the next generation of New York artists and intellectuals, who would transform the city into the next great center of international modernist culture.”

- Louise Lippincott, Carnegie Institute

🇷🇺 LGBT History of Russia

- Homosexuality in Ancient and Medieval Russia

- A Cross-Dressing Epic Hero: the Russian Folk Epic of Mikhaylo Potyk, Where He Disguises Himself as a Woman

- The Homosexuality of Russian Tsars: Vasily III and Ivan IV "the Terrible"

- Uncensored Russian Folklore: Highlights from Afanasyev's "Russian Secret Tales"

- Homosexuality in the 18th-Century Russian Empire — Europe-Imported Homophobic Laws and How They Were Enforced

- Peter the Great's Sexuality: Wives, Mistresses, Men, and His Connection to Menshikov

- Russian Empress Anna Leopoldovna and the Maid of Honour Juliana: Possibly the First Documented Lesbian Relationship in Russian History

- Grigory Teplov and the Sodomy Case in 18th-Century Russia

- Russian Poet Ivan Dmitriev, Boy Favourites, and Same-Sex Desire in the Fables 'The Two Doves' and 'The Two Friends'

- The Diary of the Moscow Bisexual Merchant Pyotr Medvedev in the 1860s

- Maslenitsa Effigy: The "Man in Women's Clothes" of Russia's Pre-Lent Carnival

- Sergei Romanov: A Homosexual Member of the Imperial Family

- Andrey Avinoff: A Russian Émigré Artist, Gay Man, and Scientist

References and Sources

- Lippincott, Louise. Andrey Avinoff: In Pursuit of Beauty. Carnegie Museum of Art. 2011

- Shoumatoff, Alex. Russian Blood: A Family Chronicle. 1982

- Shoumatoff, Nicholas. Andrey Avinoff Remembered.

- Tags:

- Russia

- Queerography