Was Atatürk Gay or Bisexual?

What memoirs, biographies, and British intelligence reports say about the sexuality of Turkey’s founder.

- Editorial team

In this article, we first provide a brief overview of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s biography, his personality, and his short family life. Then, drawing on memoirs, diplomatic documents, and historians’ works, we analyze the origins and evolution of the claim that he may have been homosexual or bisexual.

Atatürk’s Life Path and Political Career

Atatürk went by several names, but here we will use the form “Mustafa Kemal Atatürk.” Mustafa in Arabic means “the chosen one,” and the name Kemal means “perfection” — he received it at military school for diligence. He received the surname Atatürk, “Father of the Turks,” in 1934 after the Surname Law was adopted, making surnames mandatory for all residents of Turkey.

He was born during the Belle Époque — a period associated with relative peace and economic prosperity from the late 19th century up to World War I — when the Ottoman Empire was trying to modernize. At the same time, nationalism was rising worldwide, and ethnic and racial prejudices were growing stronger. The exact date of his birth is unknown because different calendars were used. Later, he himself set his birthdate as May 19, 1881, linking it to the start of the national liberation struggle in 1919.

In Ottoman censuses, people were recorded by religion rather than ethnicity. Mustafa Kemal’s family was registered as Muslim and spoke Turkish. His father was from Salonika (today Thessaloniki), and his mother came from nomadic Turks. Some historians suggest that his father may have had Slavic or Albanian origins, but most consider him Turkish.

His father wanted to send Mustafa to a new school with a modern curriculum, while his mother wanted a traditional Muslim school. In the end, he studied in both. In 1888, his father died when Mustafa was 7 years old. Later, his mother married a man with four children, and, having lost his position as the senior male in the household, Mustafa was able to leave the family in order to pursue his education.

From a young age, he admired Western military uniforms. In 1896, he entered the military school in Monastir (today Bitola), and three years later continued his studies at the Ottoman Military Academy in Constantinople (today Istanbul). At the academy, it was forbidden to read anything except textbooks. After graduating in 1902, he entered the Imperial Staff College — the highest institution for training staff officers — and successfully completed it as well. By the time he joined the army, he had about 13 years of military education behind him.

He served on different fronts: in 1911–1912 he fought in Tripolitania (a historical name for a region in today’s Libya) against Italy, and in 1912–1913 he fought in the Balkans during the Balkan Wars. In World War I he became one of the key commanders: in 1915, at Gallipoli, he thwarted an amphibious landing by Entente troops (the Entente — the coalition opposing the Central Powers in World War I). He then served on the Caucasus Front against the Russian Empire and on the Syrian front against British forces. After the 1918 armistice, which meant the Ottoman Empire’s de facto surrender and the beginning of its occupation by the victorious powers, Mustafa Kemal opposed the partition of the country and foreign occupation and decided to act.

In May 1919 he arrived at the port of Samsun as an inspector of the Ottoman army: formally he was supposed to oversee order and the disarmament of troops, but in practice he began organizing the independence movement. A year later, in Ankara, he created the Grand National Assembly — an alternative to the government in occupied Constantinople. In 1920–1922 he led the War of Independence against Greece and other intervening forces. Victory led to the 1923 treaty recognizing Turkey’s independence. On October 29, 1923, the republic was proclaimed, and Mustafa Kemal became its first president.

As head of state, Atatürk carried out large-scale reforms. In 1924 the caliphate was abolished, and the country moved to secular legislation based on European legal systems. In 1928 the Latin alphabet was introduced. He reformed education and expanded women’s rights, granting them legal equality and voting rights earlier than many European countries. At the same time, he pursued industrialization and strengthened the separation of religion and state. The reforms met resistance, especially in conservative regions, and uprisings were suppressed by the army. In foreign policy, he sought neutrality.

In the last years of his life, Atatürk suffered severely from liver cirrhosis. On November 10, 1938, he died in Istanbul, at Dolmabahçe Palace, which at the time served as the presidential residence.

Character Traits and Everyday Habits

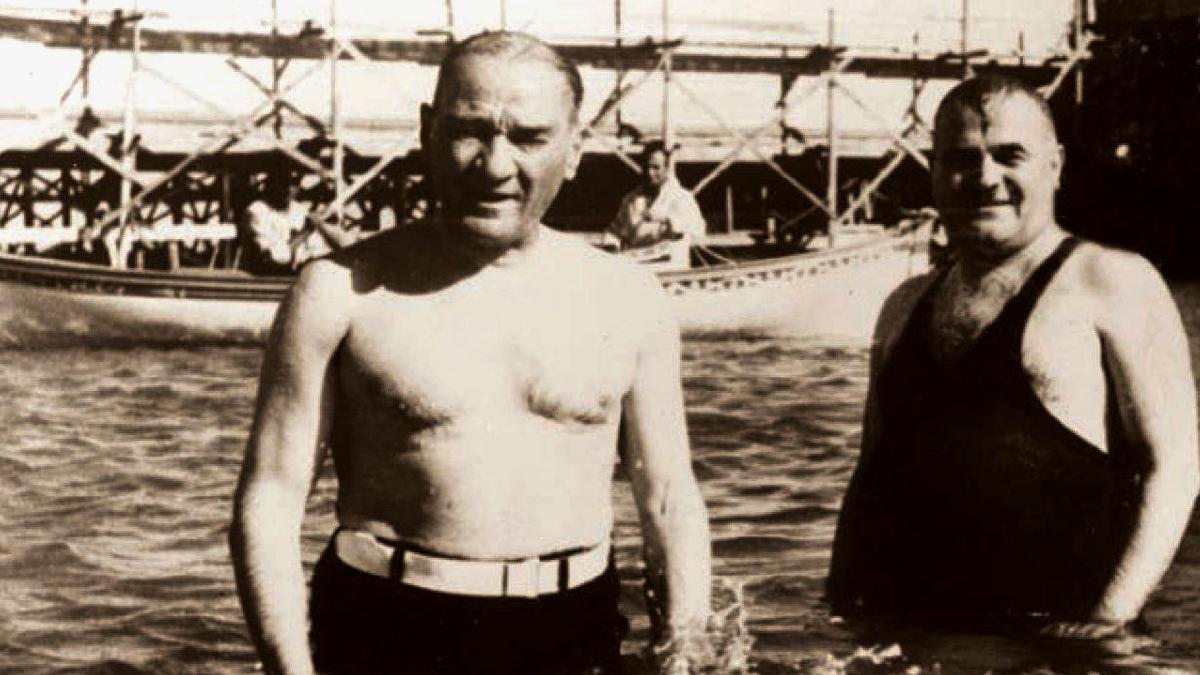

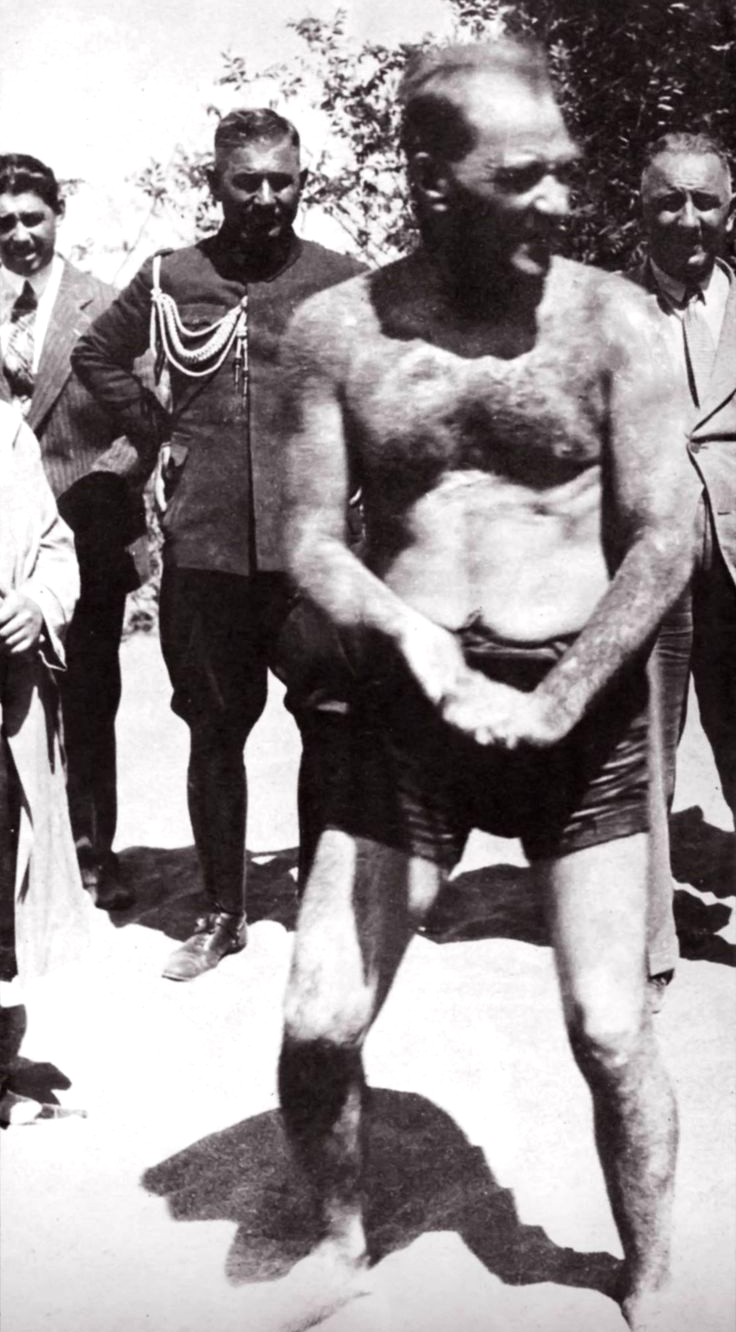

Contemporaries remembered Atatürk as a fit, medium-height man — about 174 cm (5 ft 8.5 in) tall and around 75 kg (165 lb). He had light-blue eyes, broad shoulders, a well-developed chest, and an always neat appearance. He wore European suits and deliberately shaped the image of a “new Turk.” People noted his decisiveness, his readiness to take unpopular steps, his charisma, and his intolerance for sloppiness and incompetence. In conversation, he often cut interlocutors off sharply and gestured actively.

Those close to him described him as someone with a nocturnal routine. He preferred to work and discuss affairs late into the night, slept little, and could sit at the table for many hours, going through future reforms and laws.

In an interview, he said about himself:

“There is one trait I have had since childhood — in the house where I lived. I never liked spending time with my sister or with a friend. From early childhood I always preferred to be alone and independent — and that is how I have always lived. I have another trait as well: I never had patience for any advice or instruction that my mother — my father died very early — my sister, or any of my closest relatives gave me, as they saw fit. People who live with their families know that there is always no shortage of innocent and sincere advice coming from the left and the right. There are only two ways to deal with it. Either to ignore it, or to submit to it. I believe that neither of these ways is wrong.”

- Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

In everyday life, Atatürk regularly drank alcohol. Typically, he drank about half a liter of rakı (a strong Turkish anise-flavored spirit). He smoked a lot as well — mostly cigarettes.

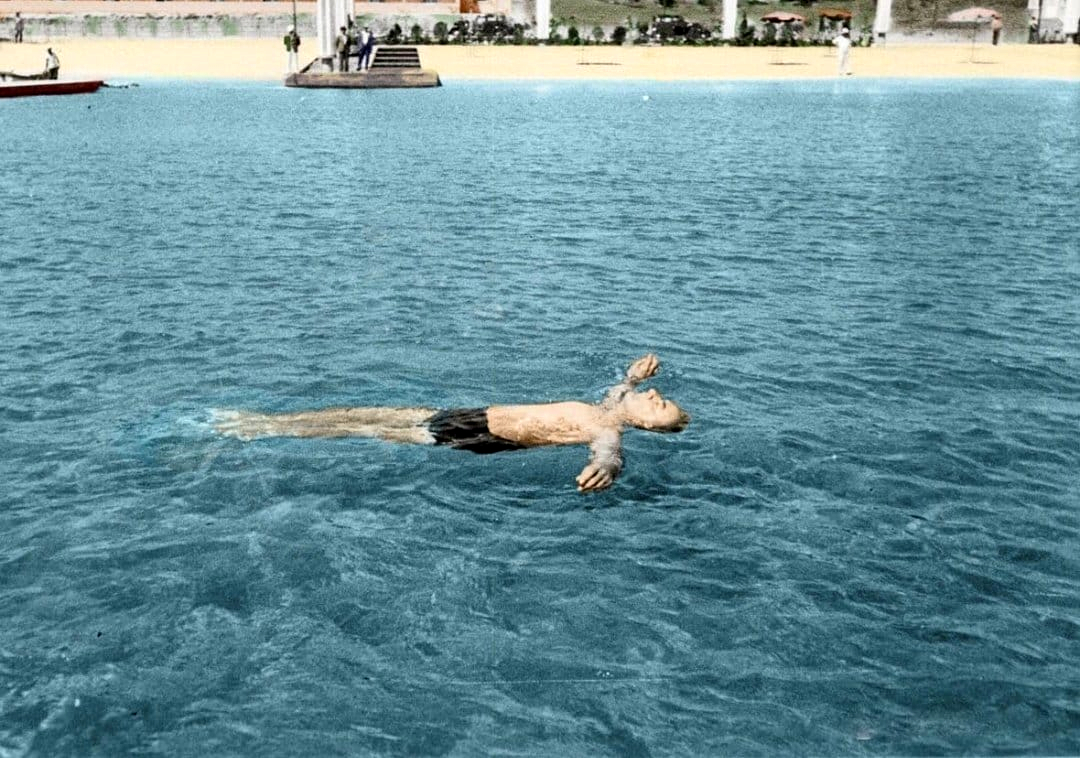

At the same time, he loved music and dancing, rode horses, swam, played backgammon, and played billiards. He was especially interested in the folk dance zeybek (a traditional dance where the performer displays strength and courage), traditional Turkish oil wrestling, and Rumelian songs — that is, songs associated with people from the Balkans (Rumelia was the Ottoman term for its Balkan lands). In his free time, he most often read history books. Atatürk appreciated sharp — sometimes harsh — humor, but he could also laugh at himself. He was deeply affectionate toward animals, especially his horse named Sakarya and his dog named Fox.

In military schools, he studied Arabic, Persian, and French. He spoke French fluently. He knew Arabic at a level that allowed him to read and interpret the Qur’an on his own. At the Military Academy, he chose German as his second foreign language. He understood English, but read English slowly.

There is no consensus on his religious views. Some researchers considered him a skeptic, an agnostic, a deist, or even an atheist. Most authors, by contrast, described Atatürk as a devout Muslim. His adopted daughter recalled that he prayed before battles. In the early 1920s, he publicly said “our religion,” emphasizing the unity and greatness of Allah. In a 1933 interview, he rejected agnosticism and declared faith in a single Creator. At the same time, he sharply criticized the fact that people did not understand the Qur’an, and believed that thoughtful reading could lead Turks to abandon Islam.

Marriage, Divorce, and an Adoptive Family

Atatürk was married only once. His only wife was Latife Uşaklıgil. She came from a well-known and wealthy family of shipowners from the city of Smyrna (today İzmir). Latife received a European-style education, read widely, knew how to hold a conversation, and was interested in many areas of life. They met on September 8, 1922, when the Turkish army recaptured Smyrna from Greek forces. When Atatürk was about to leave, he made it clear to Latife that she mattered to him and said: “Don’t go anywhere. Wait for me.”

On January 29, 1923, Atatürk secured Latife’s family’s consent to the marriage. During the wedding ceremony, Latife did not cover her face, even though at the time brides customarily did so. Her gesture became a noticeable step against old traditions.

After the wedding, the newlyweds did not go on a traditional honeymoon because parliamentary elections were approaching. Atatürk immediately returned to state work. Later, they did take a trip together, but it had political significance. During their travels, Atatürk openly presented his wife to the public. He wanted Turkish women to see a living example of a new model of behavior.

Once in Erzurum, a city in eastern Turkey, a serious conflict broke out between the spouses, and their relationship came close to breaking. On August 5, 1925, they officially divorced. Exactly why their union collapsed has never become known.

Latife’s letters and diaries were closed to the public. A court imposed a ban on their publication for 25 years. Starting in 1975, her correspondence was kept by the Turkish Historical Society. When the court ban expired, Latife’s family demanded that these materials remain unopened. As a result, detailed information about their family life still remains hidden.

Atatürk had no biological children. However, he created a large adoptive family. He took in eight girls and one boy.

Political and Media Discourses About Atatürk’s Sexuality

At the official level, Turkish authorities firmly deny any claims about Atatürk’s alleged homosexuality. Attitudes toward Atatürk’s figure are part of the foundation of state ideology in Turkey. The country has a special law that prohibits insulting Atatürk. For such words, a person can receive a real criminal sentence.

Within Turkey, the topic of Atatürk’s homosexuality is sometimes turned into a tool of political struggle. Conservative religious circles, hinting at Atatürk’s “homosexuality,” try to undermine the authority of the secular republican project. In this rhetoric, homosexuality itself is described as a “deviation from the norm” and as something alien to Turkish culture.

Outside Turkey, such accusations more often serve as a form of anti-Turkish rhetoric and a way to humiliate Turks as a people. In Greece and some Balkan countries, negative stereotypes sometimes manifest precisely through insulting statements about Atatürk. In the spring of 2007, a Greek video on YouTube captioned “Atatürk and the Turks are gay” triggered an online conflict: by a decision of a Turkish court, access to YouTube within Turkey was blocked. Later the block was lifted, and the Turkish press accused the Greek side of deliberate provocation. In March 2025, AFP reported that Greek users were widely sharing an AI-generated image of “gay Atatürk,” in which he was hugging a Black man.

Another scandal erupted in 2007 in Belgium. In the educational handbook “Fighting Homophobia,” published in the French-speaking region of Wallonia, Atatürk was listed among “famous gays and bisexuals.” After an official protest from Turkey, Belgian officials acknowledged they had made an error. They explained that the handbook’s compilers had relied uncritically on random open sources on the internet without verifying the information.

But what can we actually learn about this topic from memoirs, testimonies of contemporaries, and serious historical research?

Arguments for Atatürk’s Alleged Homosexuality

The debate about Atatürk’s sexuality is based primarily on documents produced by British military officers and diplomats in the 1920s — 1930s, as well as on memoirs and biographies. Even at the time, some sources contained assertions that he was homosexual.

British Intelligence Reports on Atatürk’s Sexuality

For the British administration in the early 1920s, Mustafa Kemal long remained a figure who was largely unknown. In January 1921, the headquarters of the occupation command in Constantinople prepared an extensive profile of Kemal. It was compiled from information provided by a former commander, school and college classmates, an agent in Constantinople, and other informants. The overview stated that Kemal was born into a modest family in Salonika and studied at a military school.

His service as a military attaché in Sofia in 1913 was highlighted separately. There, according to British reports, he indulged in “debauchery” and contracted a venereal disease (an older term broadly meaning a sexually transmitted infection — STI). The authors of these reports claimed that the illness instilled in Kemal “contempt and disgust for life,” became an obstacle to marriage, and pushed him toward “homosexual debauchery.” The same profiles emphasized that at the front he behaved with recklessly brave courage.

The British Prime Minister David Lloyd George went even further in private assessments. He called Kemal an “alcoholic pederast” (a slur, historically used to accuse a man of male-male sex) and claimed that on one occasion Kemal’s envoy in London had to be literally pulled out of “sodomy” in a brothel.

A special role in shaping British perceptions of Atatürk belonged to General Charles Harington, commander of the British Army of the Black Sea, which occupied parts of Turkey after World War I. Harington controlled a well-organized information source that collected relatively accurate data about Atatürk in the early 1920s. The task was practical: to understand how to persuade Kemal to negotiate.

Unlike many diplomats and ministers, Harington did not react with hostility toward the Turks because of their victories. He developed a strategy of bluff and deterrence: to signal readiness to use force, but not allow another catastrophic war. His decisions were based on a certain understanding — and even respect — for the opponent, whereas a significant part of the British leadership saw the Turks as an “insignificant and evil race” and was furious at Kemal’s goals and successes. Because of this, his reports could not simply have been written out of personal animosity.

In one report in January 1921, Harington repeated motifs that had already appeared in other military accounts: in his words, the venereal disease “apparently instilled in Atatürk contempt and disgust for life, forbade marriage and pushed him into homosexual debauchery, and he became somewhat excessively fond of alcohol — but he was still charismatic and capable, the only incorruptible leader in Turkey, a patriot.”

Later, the British historian A. L. Macfie, analyzing these and other sources, wrote that Mustafa Kemal in his youth really was sexually promiscuous and openly bragged about his affairs. When asked what quality he valued most in a woman, he allegedly replied: “availability.” Macfie repeats the version that Kemal may have contracted a venereal disease while serving as a military attaché in Bulgaria in 1913. That experience, he writes, for a time instilled in Kemal contempt for life and led him to indulge more often in what a British military-intelligence report called “the homosexual vice.” At the same time, Macfie himself notes that such information could well have come from Atatürk’s political enemies and served as an attempt to discredit him.

Rıza Nur’s Memoirs: Atatürk “Caught” With His Wife’s Nephew

Alongside British sources, stories about Atatürk’s homosexuality also began spreading through Turkish memoir literature. In 1929, the memoirs of the former minister Rıza Nur were published in Paris. In the early years of the Turkish Republic, he served as Minister of National Education and later as Minister of Health. He later entered into a sharp conflict with the government and left Turkey in 1926. Many contemporaries considered him mentally ill. In his own books, Nur himself writes about his psychological difficulties and calls himself a neurasthenic (a historical diagnosis once used for chronic fatigue, anxiety, and irritability — not a modern clinical category).

In his memoirs, Nur says that at one point he himself fell in love with a young man. Then, in Volume 4, he claims that Mustafa Kemal had sexual relations with Halil Vedat Uşaklıgil (often referred to as Vedat), the nephew of his wife Latife Hanım. In his version, Latife Hanım caught them during sex, after which a scandal broke out that led to the divorce, and Vedat’s aunt allegedly ultimately drove him to his death.

Here is how he describes the episode:

“As it turned out, two or three days before the divorce affair, Latife, her brother İsmail, and Melahat, the daughter of Süreyya Pasha, went to Ankara. They were guests in Çankaya. At that time, Mustafa Kemal’s secretary was Halit Ziya’s son, Vedat. A handsome, moustacheless young man. One evening, when dusk was already falling, İsmail and Melahat went out onto the balcony. They saw Vedat doing this with Mustafa Kemal under a tree. They called Latife. She saw it too. A terrible scandal erupted. Latife said to Mustafa Kemal: ‘I saw everything, I endured everything. I can’t endure this anymore.’ The Gazi [i.e., Atatürk — “Gazi” was an honorific meaning a victorious warrior] slipped away and went to İsmet’s house. ‘I will divorce this woman at once,’ he said. İsmet convened the Council of Ministers early in the morning. They made the decision on the divorce.”

- Rıza Nur, about Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

Nur then gives another story in which Atatürk supposedly shifted his attention to his wife’s younger sister:

“According to Latife’s words, in those days, once her younger sister was visiting her. Mustafa Kemal made an advance on the girl. She tore herself free from his hands and ran away, ran into her sister’s room. Mustafa Kemal entered the room with a revolver in his hand. The sister, hugging the girl, shielded her with her own body. Mustafa Kemal fired, but, fortunately, the servant Bekir — who had been close to Mustafa Kemal for a long time and knew everything — grabbed his hand, and the bullets went harmlessly; they say he fired three times…”

- Rıza Nur, about Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

Turkish historians generally treat these stories with extreme skepticism. For example, İ. Ortaylı called Rıza Nur’s memoirs “gossip with no historical value.” Nevertheless, these texts continue to circulate online. In 2013, the Turkish blogger Tunçay Tokat posted a photograph of Atatürk on Facebook with the caption “Was Atatürk gay?” He explained that he had learned “this version” from Volume 4 of Rıza Nur’s book. The post led to a court case.

Atatürk’s alleged lover, Halil Vedat Uşaklıgil, was born in 1904 in Istanbul into a writer’s family. After the wars, Vedat traveled a great deal with his family across European cities, especially often living in Bern and Paris. On Atatürk’s order, he transferred from the Ottoman Bank into the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Latife Hanım was his cousin, and thanks to his talent for playing the piano, Vedat was able to get to know Atatürk closely. Later, he was sent to London for diplomatic service. On December 3, 1937, while serving as first secretary of the embassy in the capital of Albania, he took his own life by ingesting medication. According to one version, he was murdered.

Atatürk’s Biographers on “Losing Faith in Women” and an Attraction to Young Men

Texts describing Atatürk as a man with troubled or “deviant” sexuality also appear in Western biographies. The British biographer H. C. Armstrong wrote:

“As a result of the reaction he lost all faith in women and for a time became enamoured of his own sex. […] He had a number of open liaisons with women and with men. He was attracted to young men.”

- H. C. Armstrong, about Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

Armstrong’s book became the first biography of Atatürk in English. It was published while Mustafa Kemal was still alive and immediately caused controversy. Reviewers split: some considered it a realistic biography, others a provocative fabrication.

The next major British biographer, Patrick Balfour, wrote something similar:

“Women, to Mustafa, were a means of satisfying male appetites, no more; and, in his eagerness for new sensations, he would not have been inclined to refuse fleeting adventures with youths, if the opportunity arose and if the mood, in that bisexual fin-de-siècle era of the Ottoman Empire, came over him.”

- Patrick Balfour, about Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

Similar motifs also appeared in the work of the Turkish author İrfan Orga. Orga served as a fighter pilot under Atatürk’s command, later spent three years in the United Kingdom as a military diplomat, and there fell in love with an Irishwoman. Because cohabitation with a foreign woman in Turkey was then considered a military offense, Orga resigned and moved to the UK. He published several biographical books about Atatürk and described him like this:

“He never loved a woman. He knew men and was used to commanding. He had been trained to the harsh comradeship of the Officers’ Mess, to the infatuation with a handsome youth, to fleeting encounters with prostitutes.”

- İrfan Orga, about Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

***

Supporters of the version that Atatürk was bisexual point to Mustafa Kemal’s short marriage to Latife Hanım in 1923–1925 and to the arguments of biographers and memoirists. Opponents note that there are no conclusive documents or testimony proving Atatürk’s homosexual relationships, and that many recollections by people who worked closely with him and lived alongside him contain no hints of such relationships. For that reason, cautious skepticism predominates in academic circles.

🇹🇷 This article is part of the course “LGBT History of Turkey”:

- The Homosexuality Of Sultan Mehmed II

- Homoerotic Themes in Taşlıcalı Yahya Bey’s Ottoman Poem “Shah and the Beggar”

- Was Atatürk Gay or Bisexual?

📣 Subscribe to our Telegram channel (in Russian): Urania. With Telegram Premium, you can translate posts in-app. Without it, many posts link to our website, where you can switch languages — most new articles are published in multiple languages from the start.

References and Sources

- Armstrong H. C. Grey Wolf, Mustafa Kemal: An Intimate Study of a Dictator. 1972.

- Balfour P. Ataturk: A Biography of Mustafa Kemal, Father of Modern Turkey. 1992.

- Ferris J. Far Too Dangerous a Gamble? British Intelligence and Policy During the Chanak Crisis, September - October 1922. 2010.

- Macfie A. L. British Views of the Turkish National Movement in Anatolia, 1919 - 22. 2002.

- Macfie A. L. Ataturk. 2014.

- Orga İ.; Orga M. Atatürk. 1962.

- Simsir B. N., ed. British Documents on Atatürk (BDA). 1973 - 1984.

- Nur R. Hayat ve Hatıratım, volume 4. n.d. [Nur R. - My Life and Memoirs, vol. 4]

- Tags:

- Turkey