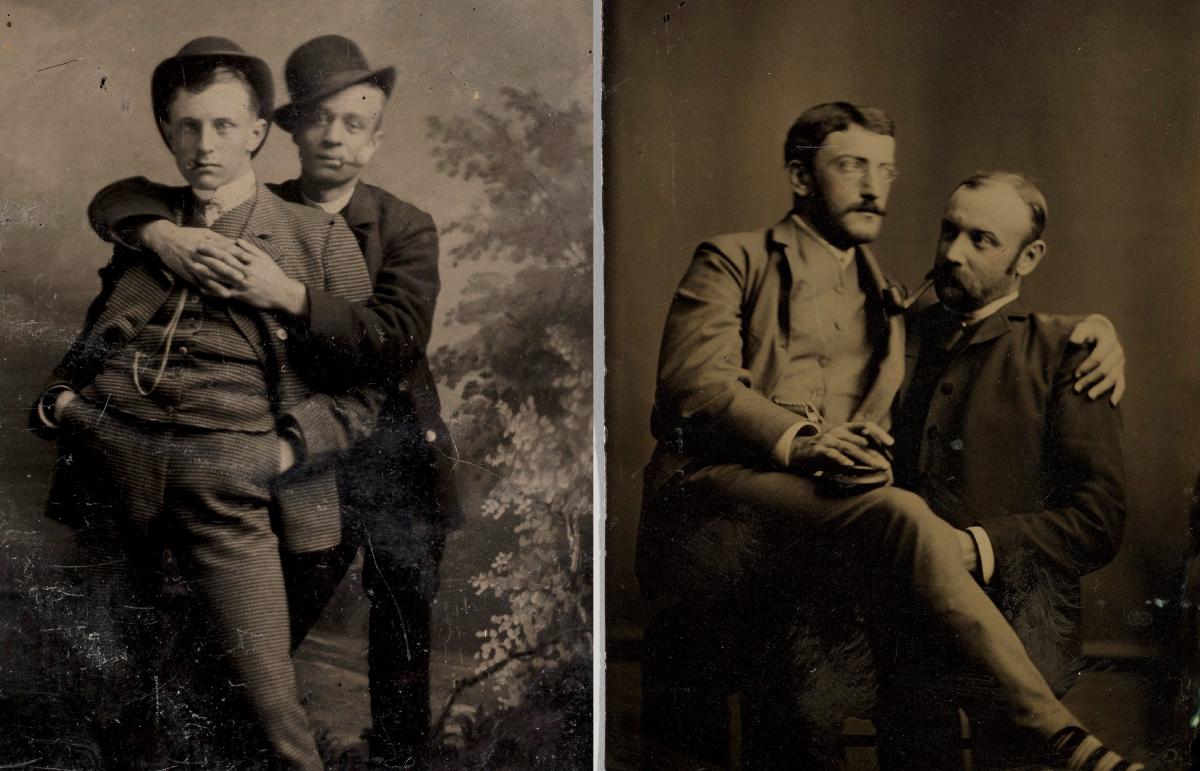

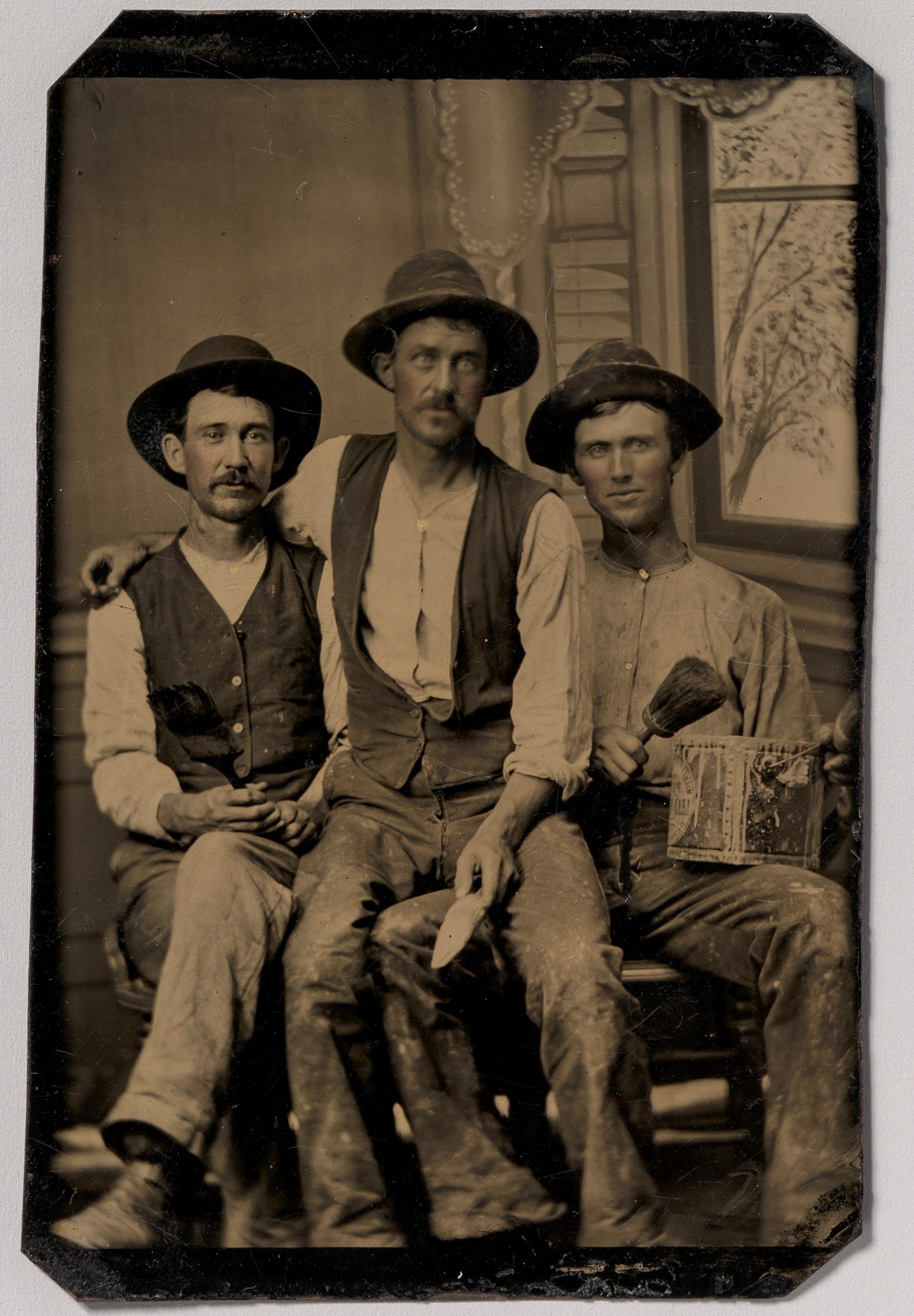

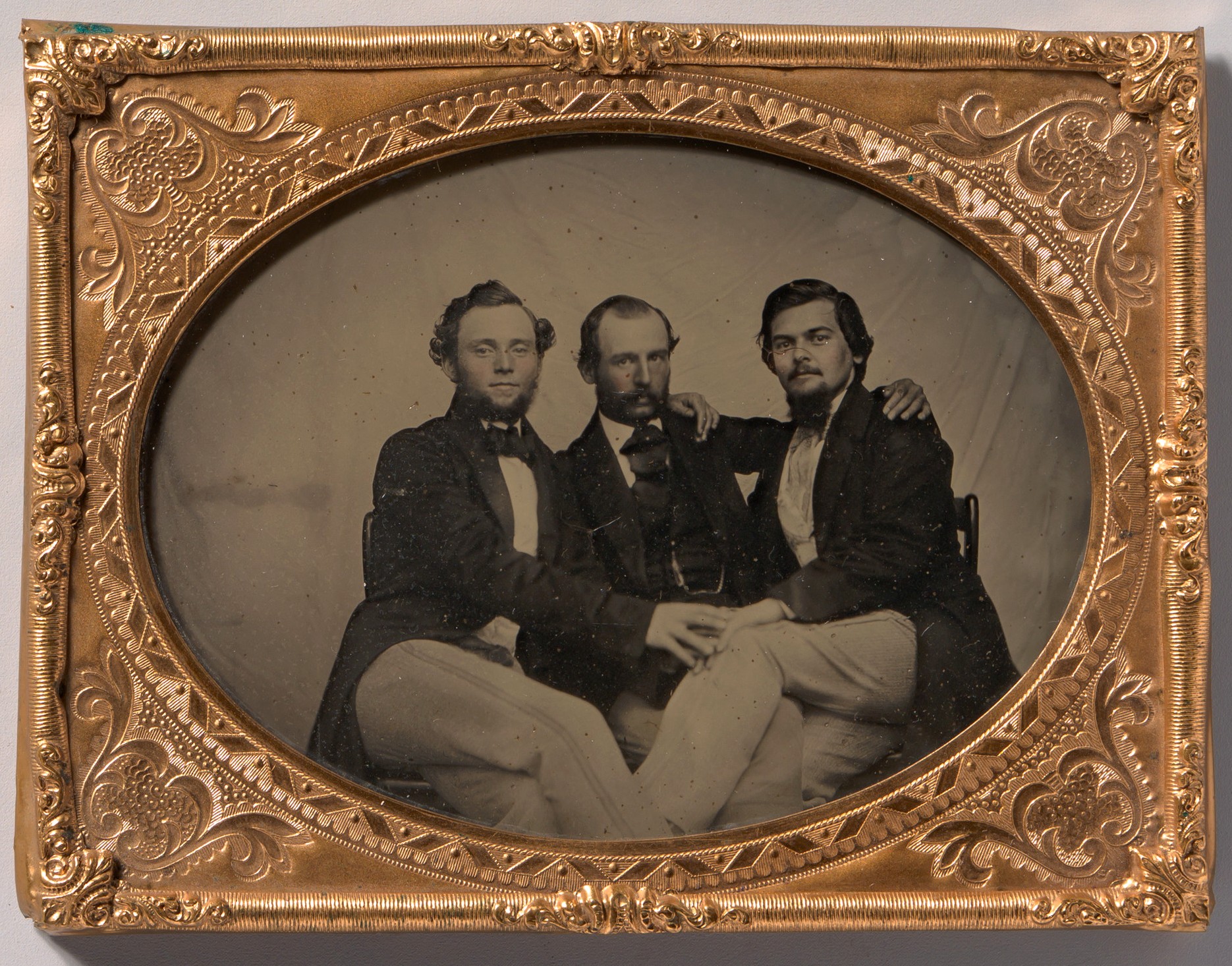

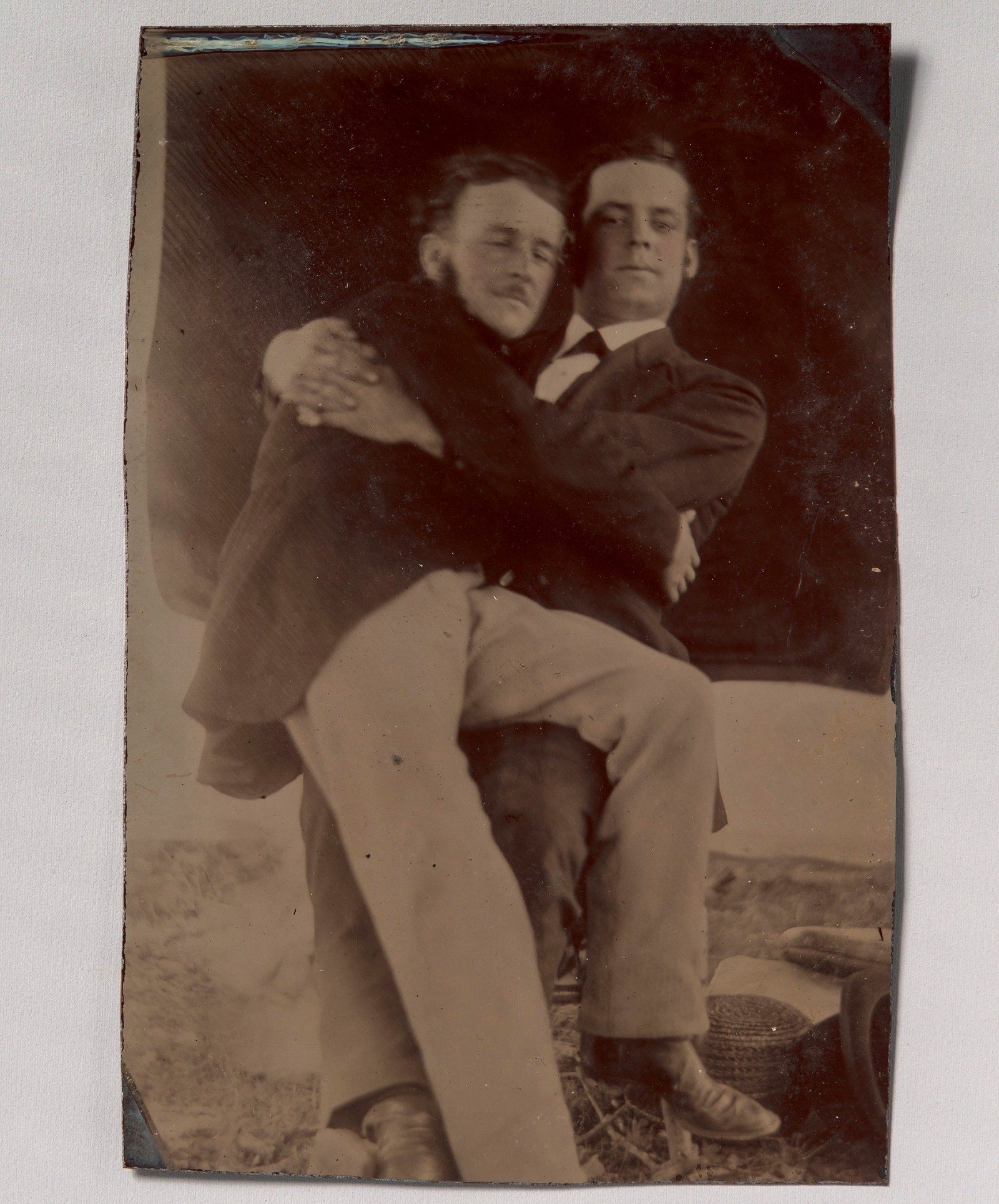

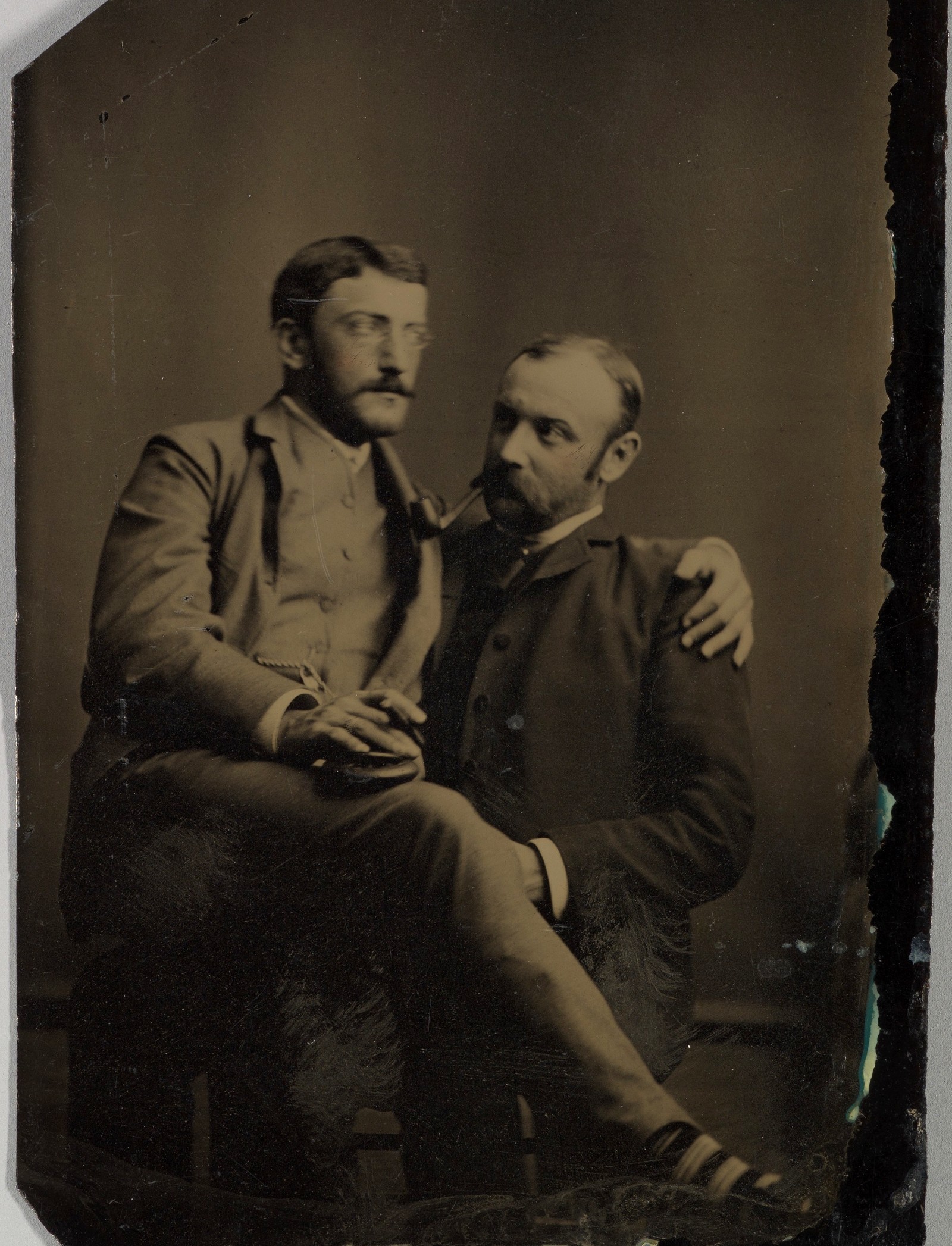

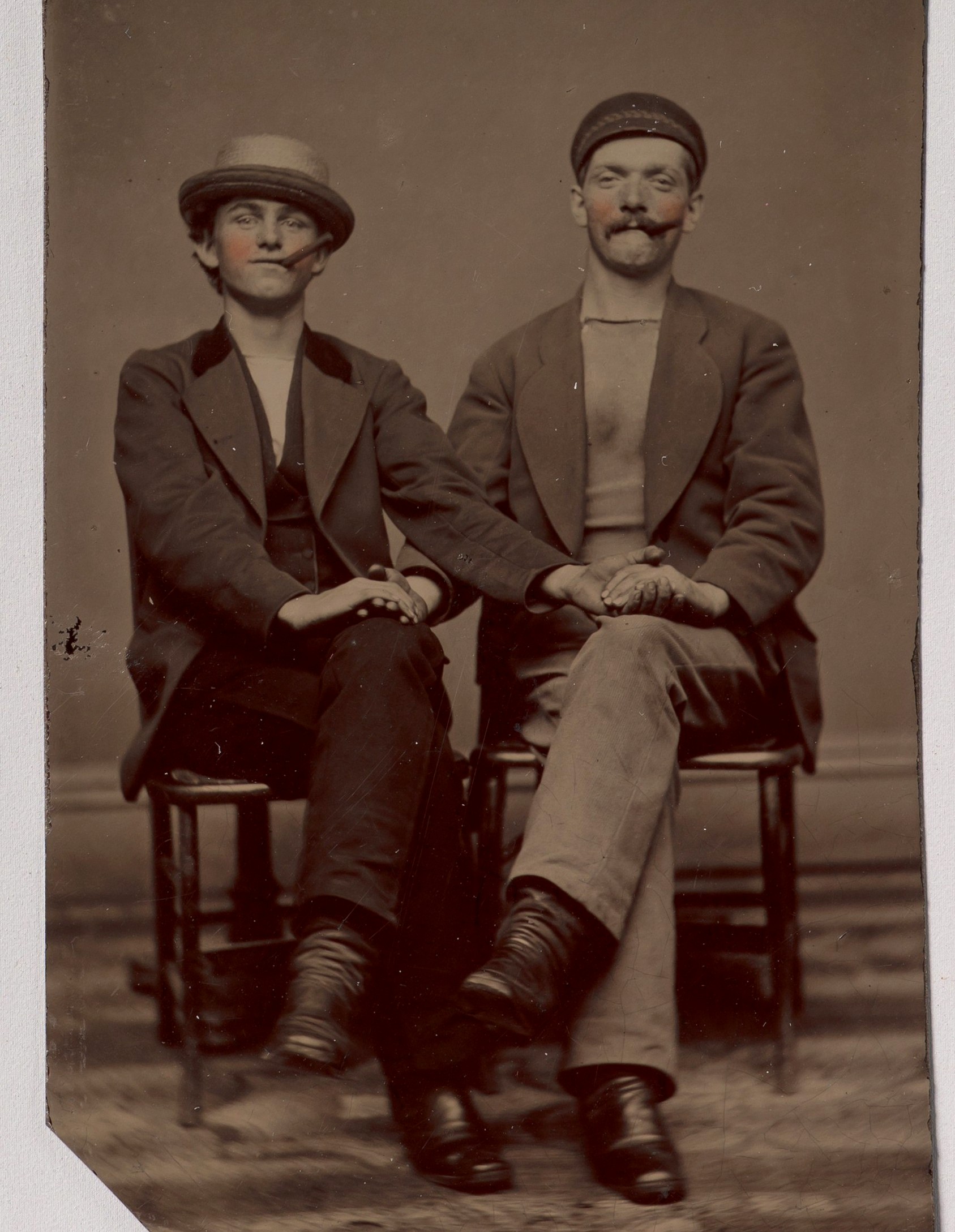

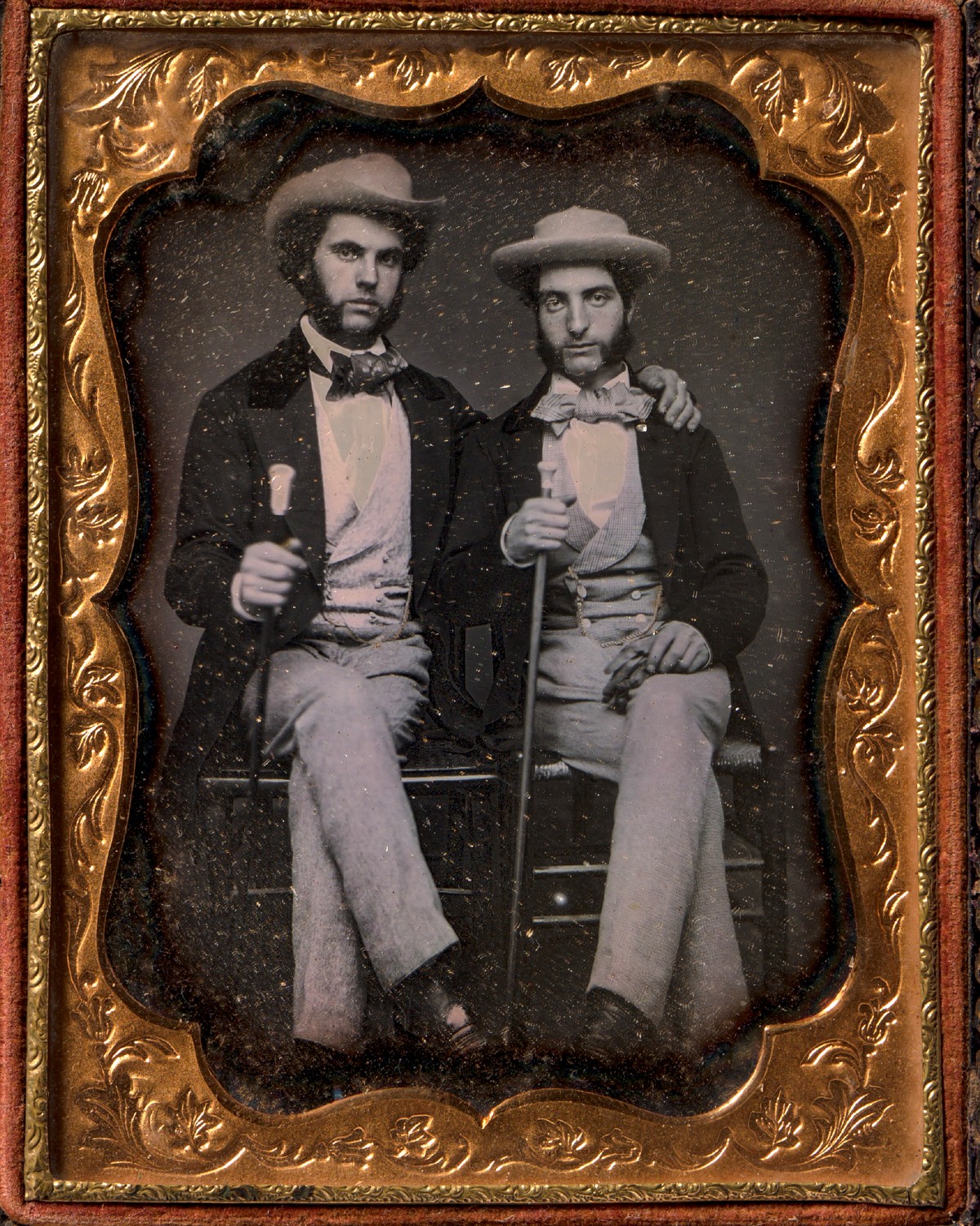

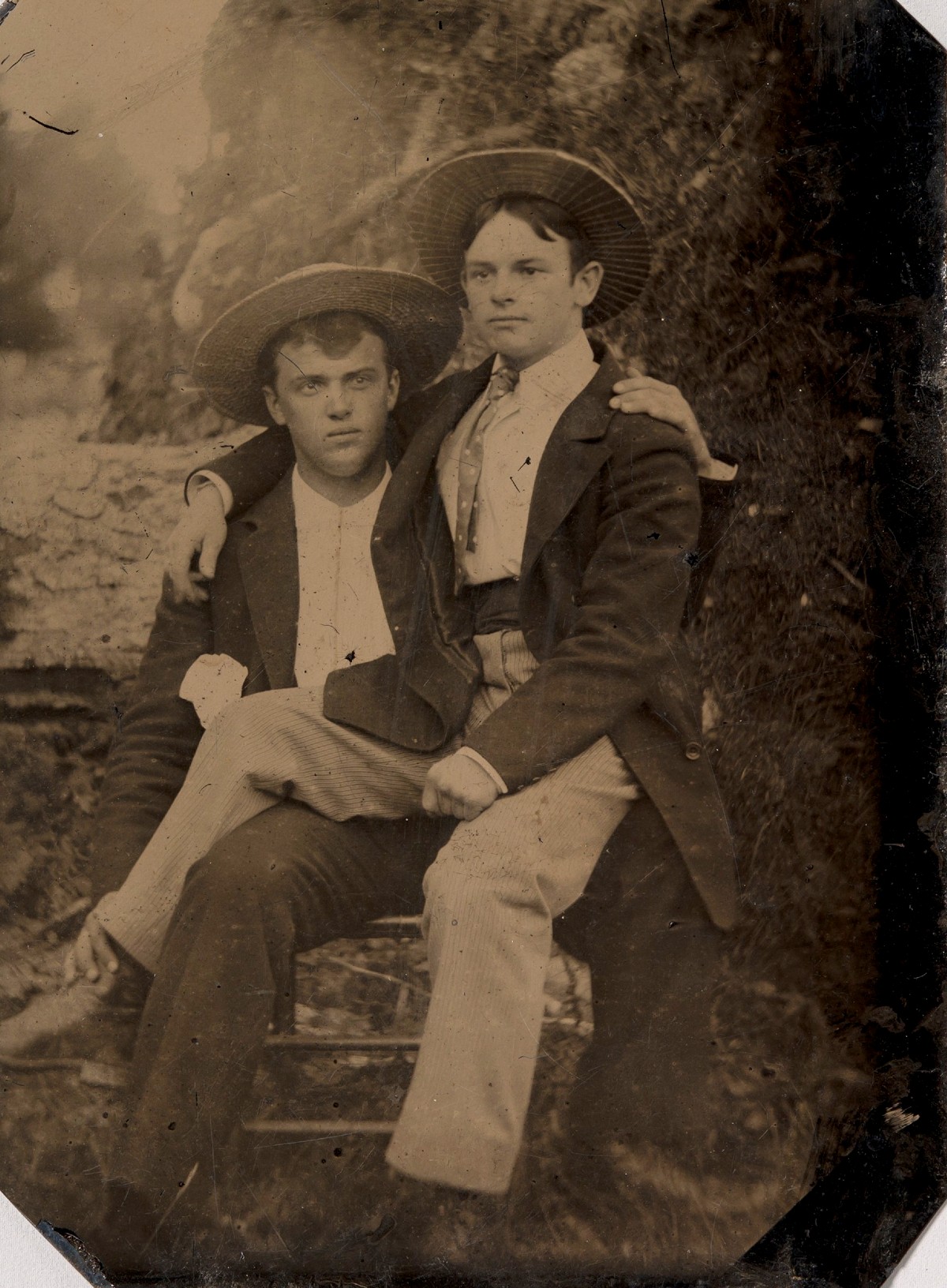

Homoeroticism of the Victorian Era: Male Intimacy in Photographs from the 1850s–1890s from the Herbert Mitchell Collection

A gallery of portraits in which men embrace and hold hands.

- Editorial team

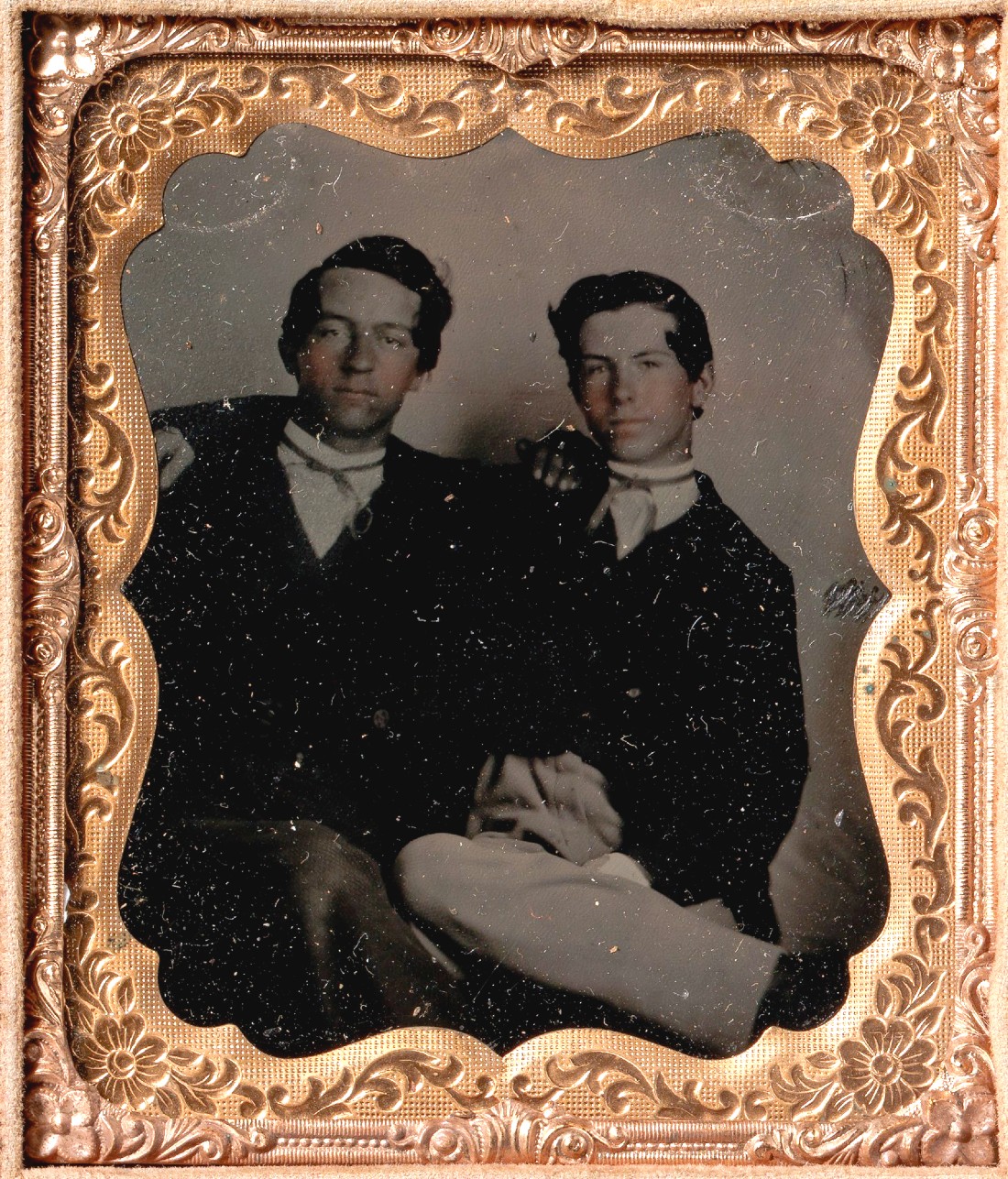

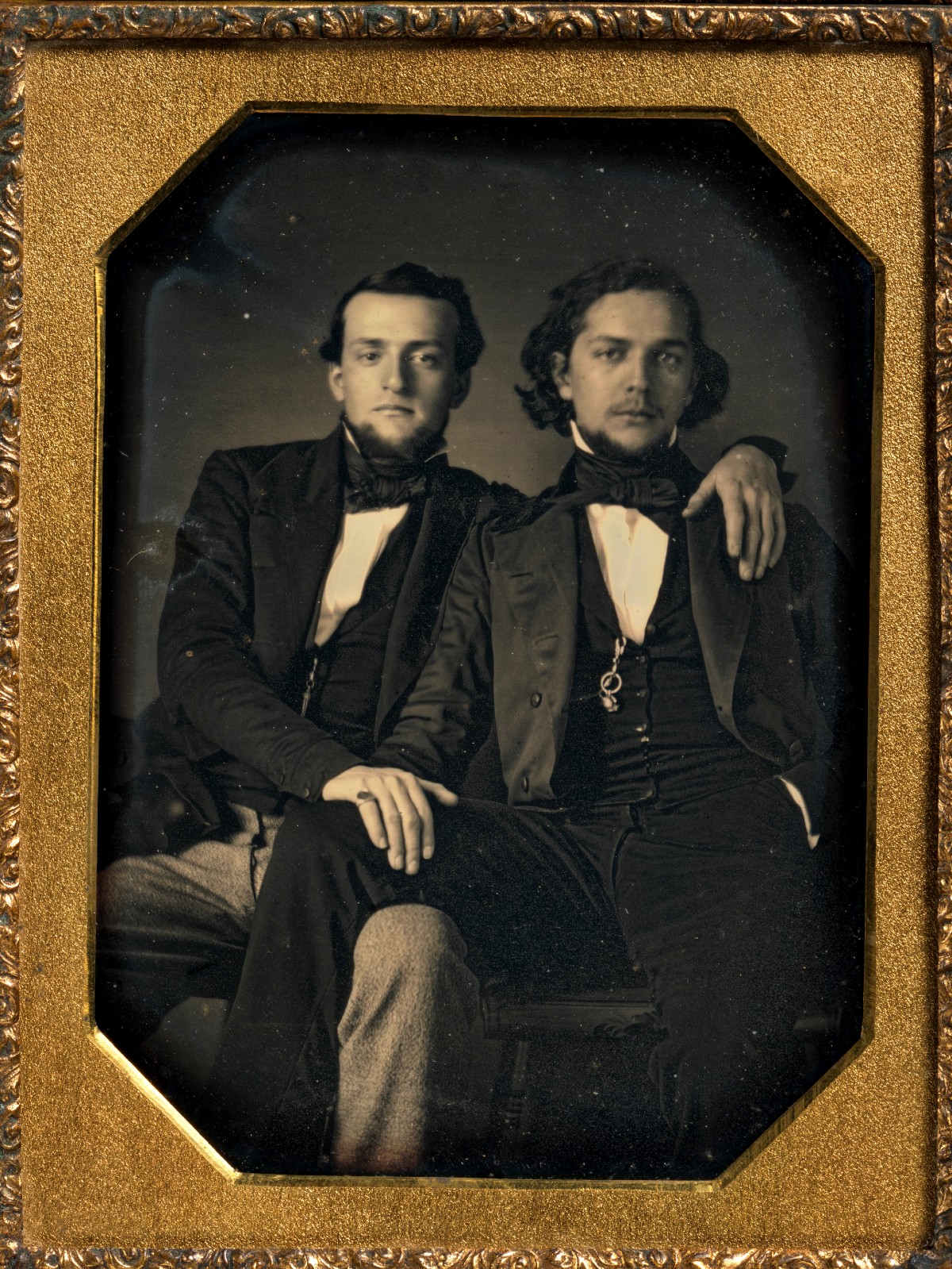

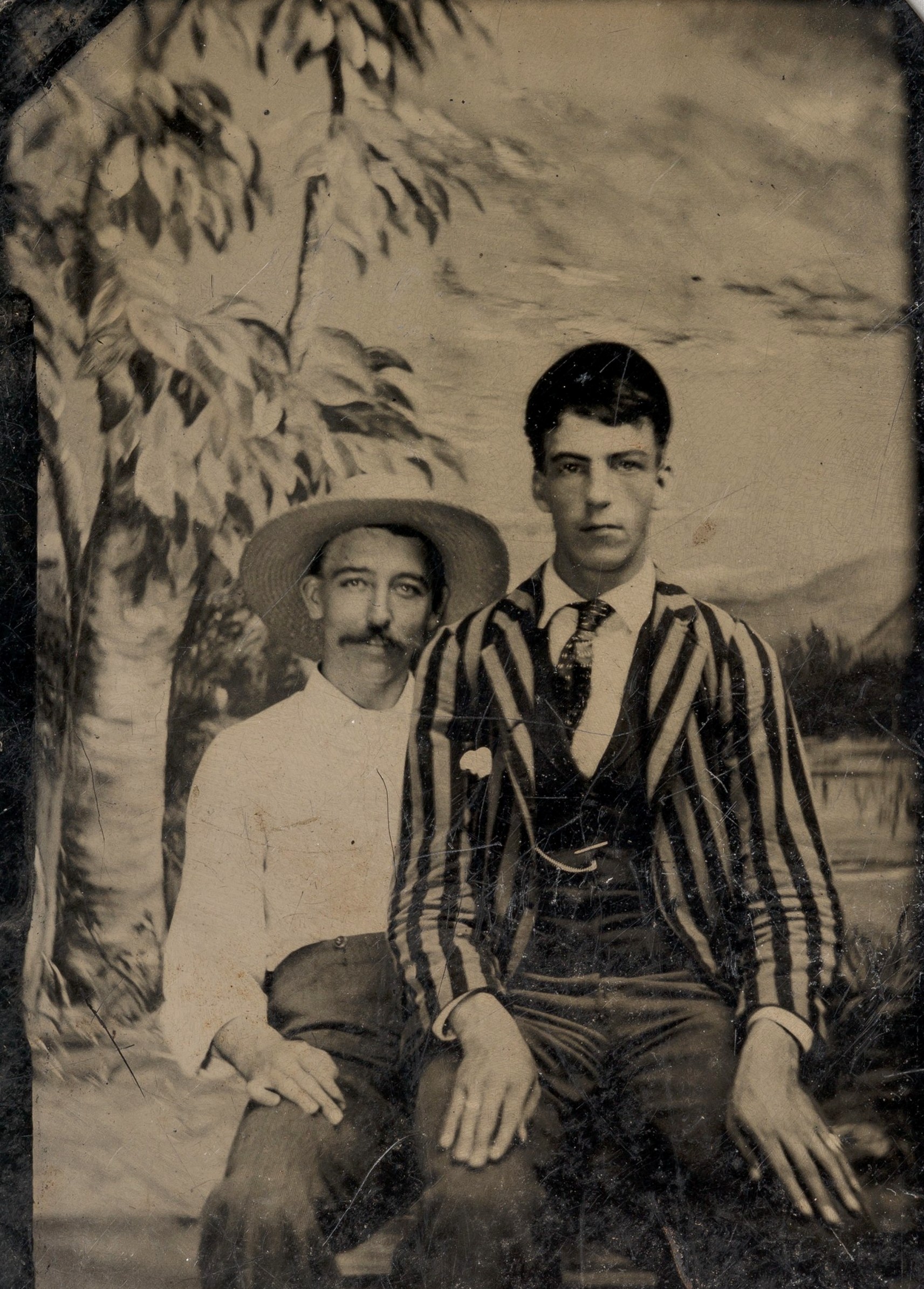

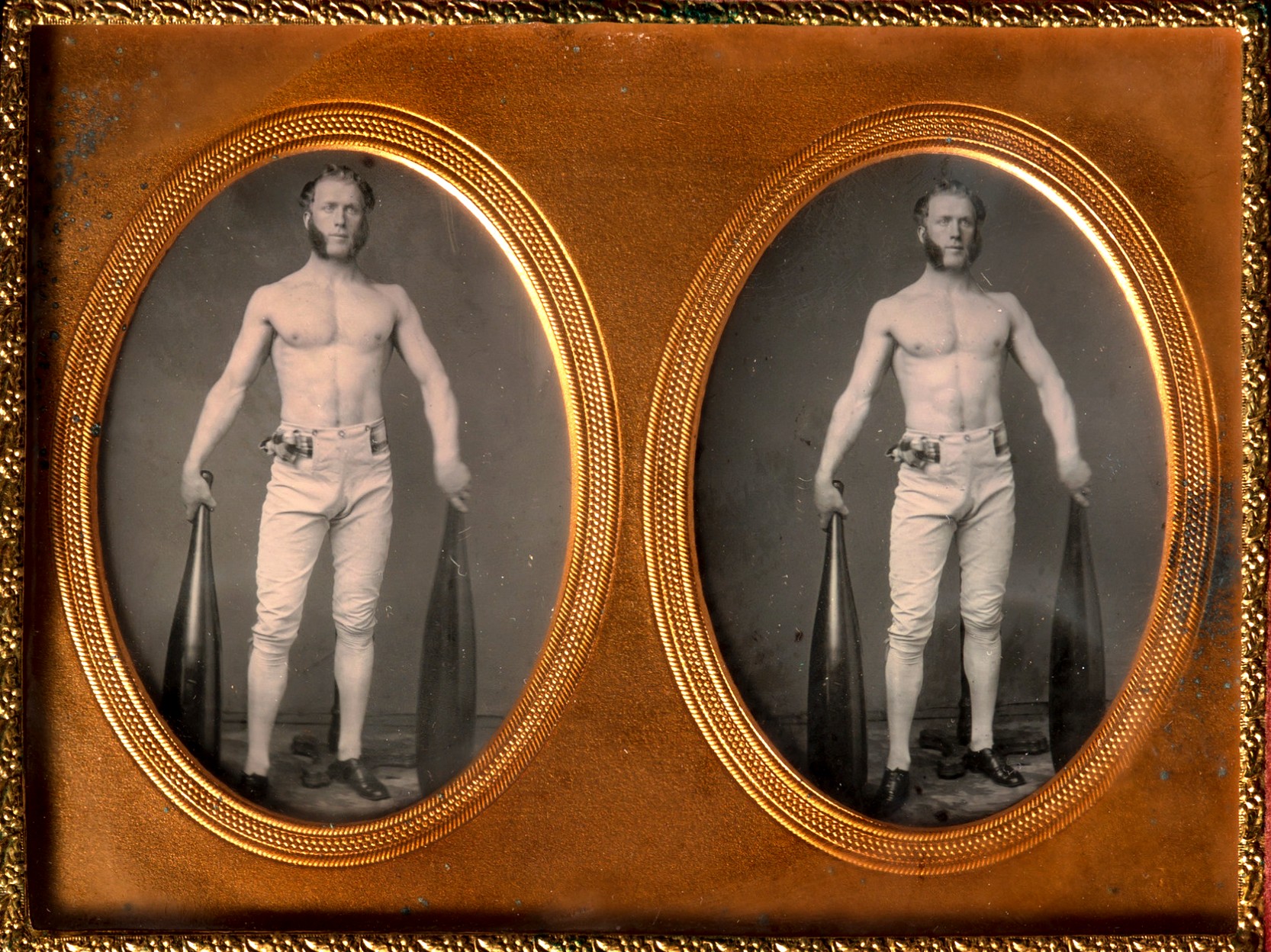

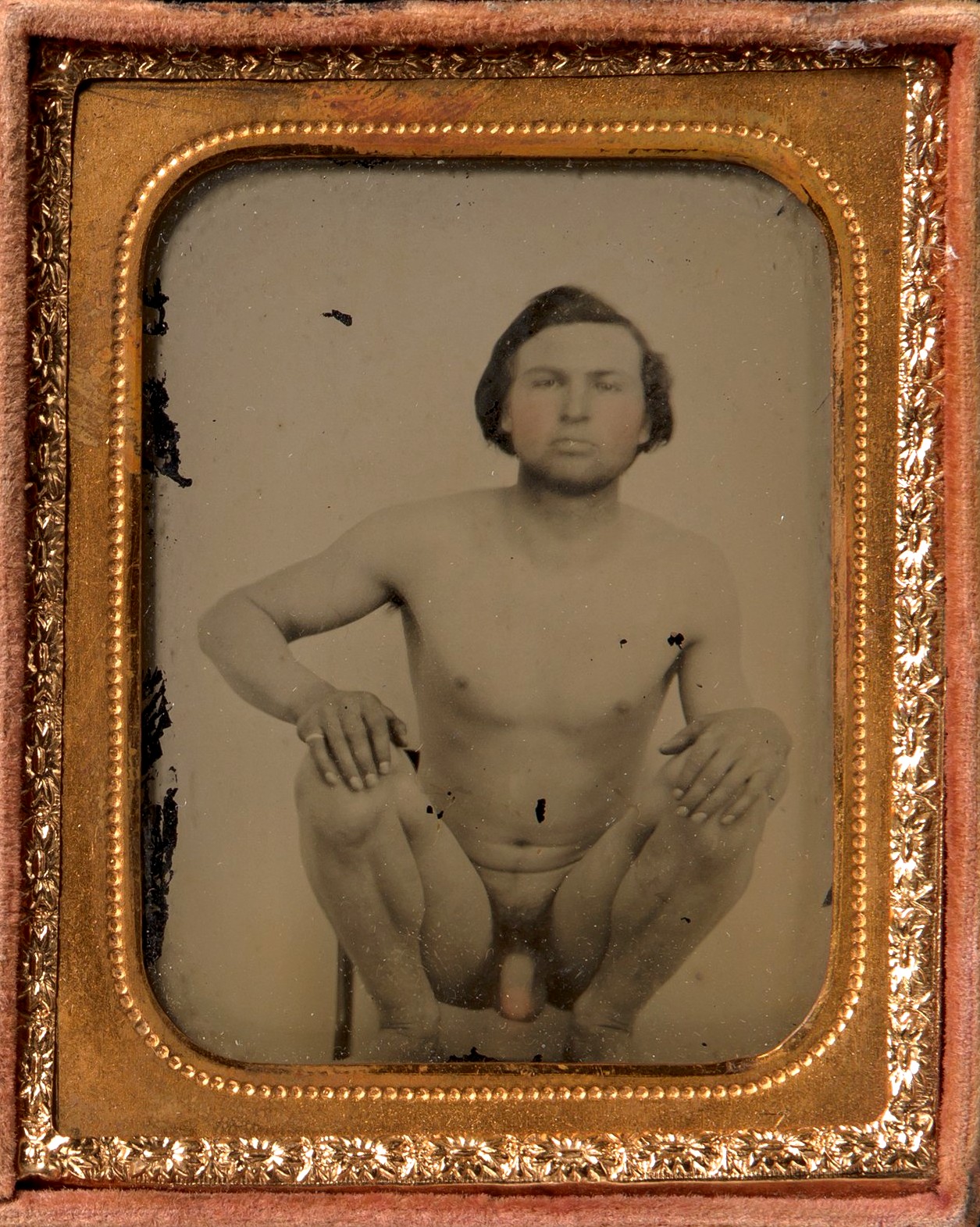

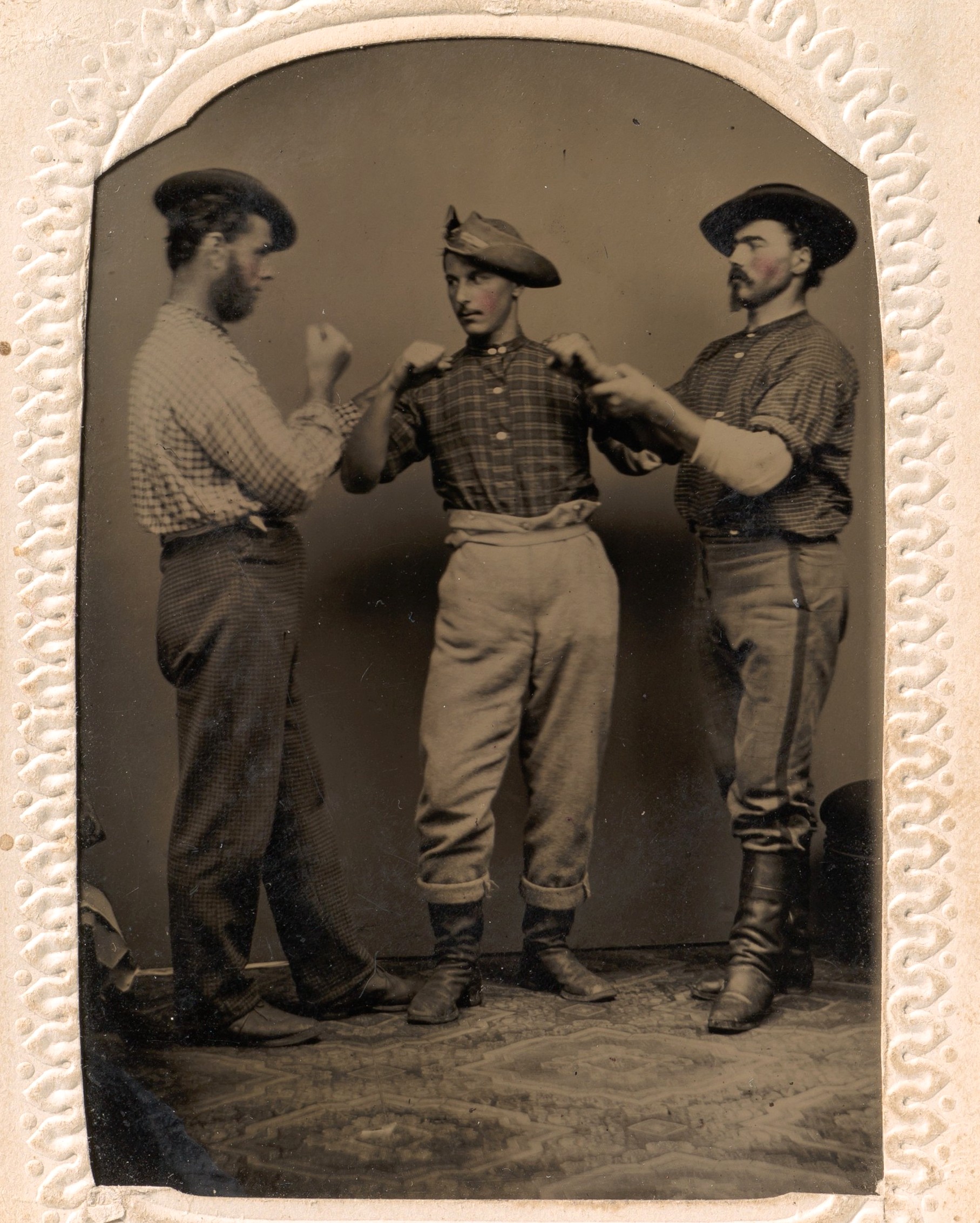

The photographs below are mostly amateur studio portraits from the second half of the 19th century (approximately from the 1850s to the 1890s), in which men pose in a very intimate manner — embracing, holding hands, placing a hand on a shoulder or on a knee.

These images are part of the collection of Reeves Herbert Mitchell (1924–2008) — an American librarian and collector who worked for many years at the Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library at Columbia University. In 2007, a large portion of his photographic collection entered the Department of Photographs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and after Mitchell’s death in 2008, the museum received many additional items from his collection through his bequest.

Gallery

A tintype is a form of early inexpensive photography. The image was produced on a thin metal plate (usually iron) coated with black lacquer.

The images in this selection depict men from a wide range of social backgrounds and occupations — from laborers and soldiers to teachers, craftsmen, and members of the professional classes. Yet we know almost nothing about most of the individuals shown: their names have not been preserved, their biographies cannot be traced, and the circumstances of the photographs have been lost. As a result, their relationships inevitably remain open to interpretation.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art proposes reading these photographs primarily as traces of a “natural and unselfconscious intimacy and physical contact” that were common among men in the pre-Freudian era, rather than as straightforward “portraits of lovers in each other’s arms.” Victorian men could indeed embrace, hold hands, and pose in very close proximity — and this was not necessarily perceived as a sexual signal.

A daguerreotype is one of the earliest forms of photography, producing an image on a silver-plated metal plate.

Contemporary viewers sometimes automatically conclude that these images reveal hidden homosexuality breaking through into the frame. This interpretation may be plausible in some cases, but it is far from the only possible explanation. More often, the men pictured may have been close friends, brothers, or fellow soldiers. The social organization of the 19th century also played an important role: men and women largely inhabited separate, homosocial worlds and typically began close cross-gender interaction mainly after marriage.

In the 20th century, norms of male friendship changed significantly. Cultural ideals gradually shifted away from open sentimentality — affectionate language, embraces, and physical closeness — toward restraint. Men increasingly avoided overt emotional expressiveness and any gestures that might be read as “too intimate.”

A backdrop was a painted cloth or panel used in a photo studio — depicting a “window,” a “street,” “columns,” or a “garden.” It served as a prop to make the portrait appear more elaborate or more “romantic.”

A stereograph consists of two nearly identical photographs of the same scene, taken from slightly different angles. When viewed through a special device (a stereoscope), they create an illusion of depth.

An ambrotype is a photograph on glass. The negative was made on a glass plate in such a way that, when placed against a dark background, it appeared as a “positive” (that is, a normal photograph). These images were usually mounted in protective cases to prevent the glass from breaking.

About Herbert Mitchell

Reeves Herbert Mitchell was an American librarian, bibliographer, and collector who lived from 1924 to 2008.

Mitchell was born on November 18, 1924, in Bangor, Maine, in the United States. He died in late October 2008 in Manhattan, New York. His attorney reported that the cause of death was complications of Parkinson’s disease. He was 83 at the time of his death. Among his closest relatives, documents and publications most often mention his sister, Dorothy Mitchell, who lived in Seattle.

Mitchell’s education was in the humanities and library science. In 1946, he graduated from the University of Maine with a bachelor’s degree. Then, in 1949, he completed Columbia University’s School of Library Service, receiving a Bachelor of Library Science degree. After finishing his studies, he worked for a time at the Art Institute of Chicago and at Cornell University. These positions gave him experience with art and scholarly collections, after which he returned to Columbia University, where his main professional career was based.

From 1960 to 1991, Reeves Herbert Mitchell worked at the Avery Library, the architecture and fine arts library at Columbia University. Within the library, he was primarily a bibliographer. For many years, he was responsible for developing the collections. University publications also describe him as the chief indexer of the Avery Index to Architectural Periodicals. This index is a reference system that helps researchers find architecture articles in journals and collected volumes, and his work was highly important for architectural scholarship.

Mitchell’s approach to building the library’s holdings was extraordinarily proactive. Early in his career, he realized that the library often missed unique materials that did not look rare or prestigious, yet had enormous historical value. A turning point was the sale of the estate of theatrical artist and designer Randolph Gunther. It became clear that materials of this kind could disappear from the scholarly record forever. After that, Mitchell began to search deliberately and persistently for rare publications through used-book sellers and antiquarian dealers.

He regularly traveled to book markets and fairs in various European cities, including London, Paris, Milan, and Rome, as well as across the United States, visiting fairs in New York, Boston, and other cities. As a result, thanks to his efforts, Avery Library assembled — according to university sources — one of the world’s most comprehensive bodies of printed and photographic evidence of the American built (urban) environment. Here, the built environment means everything connected with cities, buildings, streets, and interiors, from the late 19th century to the present.

Mitchell became especially well known among librarians and researchers for his attitude toward so-called ephemera. Ephemera are printed materials not originally intended to be kept for long-term preservation — for example, advertising brochures, prospectuses, and catalogs. Mitchell collected not only classic architectural rarities, such as old treatises and drawings, but also trade catalogs of building materials, decorative elements, paints, wallpapers, and plumbing fixtures. These seemingly ordinary publications became an indispensable foundation for researchers of historic interiors and for restorers. Thanks to Mitchell, Avery assembled the world’s largest collection of catalogs from American building-related industries.

Important exhibition projects are also associated with his name. In 1990, as part of Avery Library’s centennial, he and architectural historian Adolf Placzek curated the exhibition “Avery’s Choice: Five Centuries of Architectural Books.” In 1991, upon his retirement, an exhibition titled “Mitchell’s Choice” was organized in the rotunda of the Low Memorial Library. It presented about fifty items he had acquired for Avery over the years — from early architectural treatises to builders’ catalogs and so-called “city view books,” illustrated publications featuring city panoramas.

During his thirty-year career, Mitchell also built a collection of American view booklets and albums known as the “American View Book Collection.” He deliberately sought out such publications at yard sales, flea markets, and through used-book sellers. As a result, the collection grew to about 4,800 illustrated publications devoted to U.S. cities and regions.

As a private collector, Mitchell gathered a wide range of objects. His personal holdings included stereographs, daguerreotypes (early photographs on metal plates), majolica ceramics, porcelain figurines made of so-called Parian ware, cabinets of 19th-century architectural books, and a large amount of small-format printed ephemera. Colleagues also noted his openness: when a research topic overlapped with his interests, he readily made his materials available for books and exhibitions.

A special place in his legacy is his connection with the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. In 2007, the museum’s Department of Photographs received a major “Herbert Mitchell Collection,” which included 3,885 stereographs dating roughly from 1850 to 1920. This collection was processed as a distinct acquisition and clearly shows the scale of his holdings. After his death in 2008, the museum received, through his bequest, an enormous number of objects across multiple departments: photographs in various processes, architectural drawings, albums, scrapbooks, and cut-paper works. Judging by the inventory numbers, these items number in the hundreds and thousands.

- Tags:

- Usa