A Queer Lexicon of Ancient Egypt

Exploring Ancient Egyptian terms for same-sex practices.

- Editorial team

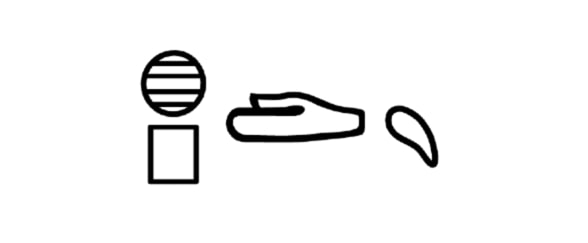

How to Read the Ancient Egyptian Language

We do not know what Ancient Egyptian truly sounded like. The main reason is simple: writing almost never recorded vowels.

Egyptians wrote in hieroglyphs, and later used two more cursive scripts — hieratic and demotic. In all three systems, what was written down was mostly consonants, along with a set of auxiliary signs. But the writing did not show which vowels stood between the consonants, whether they were long or short, or where the stress fell. What remains for us is only the word’s “skeleton”: a sequence of consonants.

For example, the spelling kȝ nḫt twt mswt (one of Tutankhamun’s names) contains no vowels, and we cannot confidently say which “a,” “e,” or “u” sounds were actually there. It is easy to imagine something similar in English if we wrote only consonants: “ct” could be read as “cat,” “cut,” “coat,” and in many other ways. Without context, reading becomes nearly impossible.

Sometimes we can narrow down pronunciation when Egyptian words and names appear in texts written in other languages — as loanwords, or spelled with a different script. Such cases help, but they are rare. And even then the original sound is usually distorted: foreign phonetics and spelling conventions “reshape” the word to fit what that language can represent. So even in good examples we are dealing not with an exact match, but with an approximate reconstruction.

To make Egyptian texts readable aloud, Egyptologists agreed on a conventional, scholarly pronunciation. Consonants are “voiced” by inserting vowels, most often e or a. Thus the spelling nfr is commonly read as “nefer,” although we do not know whether the word actually sounded like that.

This is also why names look different across traditions. In Russian usage “Tutankhamun” is often rendered as “Tutankhamon,” while English-language scholarship more commonly uses Tutanhamun.

A Queer Lexicon of Ancient Egypt

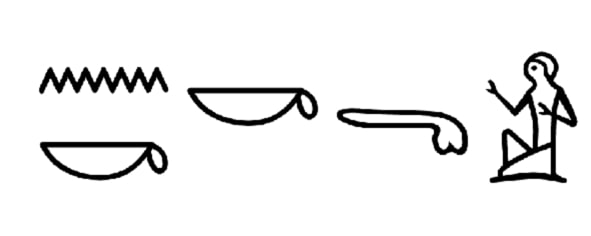

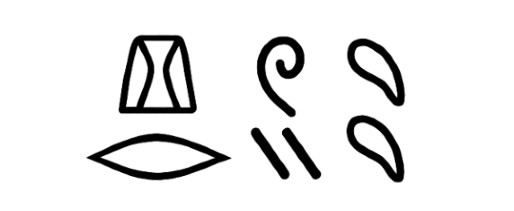

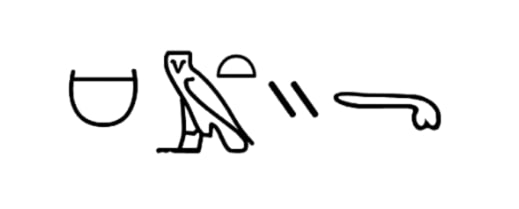

nk [nek] — to perform a penetrative sexual act

This is a basic, generally neutral verb for sex. By itself it is not marked as “sin” or “perversion”: it is simply an action word.

In funerary literature, for example in the Coffin Texts, sexuality and semen can appear as part of imagery of life-force and rebirth after death. In many formulas, a heterosexual context is clearly implied, yet there are also variants that speak of “doing nk in the anus.”

nkk(w) [nekk(u)] — a man in the receptive role in an anal penetrative act

The form nkk(w) is participial; it names the participant in a situation or the bearer of a characteristic — literally, “the one to whom nk is done.” In this sense it describes a man upon whom a penetrative act is performed.

In the Book of the Dead, chapter 125, one version of the so-called Negative Confession includes the formula: “I have not nk in nkk(w).” In other words, this means: “I did not penetrate a passive man.” The deceased declares before the gods that he did not do this.

Because of this wording, some researchers translate nkk(w) as “gay,” but that is unlikely to be a precise or appropriate equivalence.

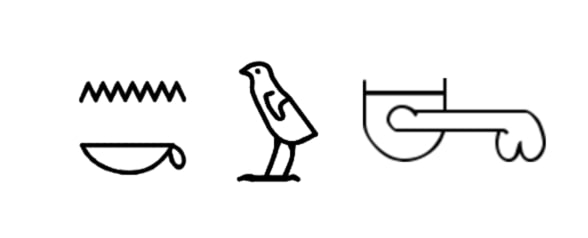

nkw [neku] — a man in the active role in a penetrative sexual act; also: a fornicator

This word is built from the same root nk, but with a different derivational suffix. In meaning nkw is the active partner — “the one who does” the penetrative act, literally “the one who copulates.”

In the sources this word can sometimes function as an insult — labeling someone regarded as sexually loose.

ḥnn [henen] — phallus; penis

The word ḥnn means “phallus” or “penis” and occurs both in ritual-religious and in medical texts. It is a masculine noun belonging to basic anatomical vocabulary.

In the Pyramid Texts (Pyramid of Unas, PT 317) it says:

“With his mouth Unas eats; with his phallus Unas urinates and copulates.”

Here ḥnn is not merely a body part but a symbol of vitality and creative power: the deceased king retains bodily and sexual functions even in the afterlife.

In medical papyri — for example, the Edwin Smith Papyrus (X,13) — the word is used in its literal sense:

“His penis became rigid as a result (i.e., it became erect).”

Here ḥnn refers to the organ’s physiological state and is used without mythological or symbolic overtones.

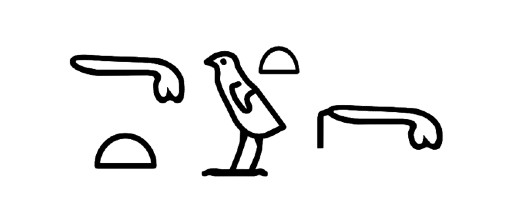

ẖr.wj [kherui] — testicles; testes

This is a masculine noun in the dual form (literally “the two”). The root is connected with ẖr “under / below,” so the expression can be understood as “the two that are below” — that is, “the lower two.”

In the Pyramid Texts (version from the Pyramid of Pepi I, PT 359) the following formula occurs:

“Horus cried out/groaned because of his eye, and Seth because of his testicles.”

This line alludes to the mythological conflict between the gods Horus and Seth: Horus suffers in his eye, while Seth suffers in his genitals.

mtw.t [metut] — seed (semen)

The word mtw.t is a feminine noun which in its literal sense means “seed, semen.” In some contexts it can also be used figuratively as “son,” i.e., “offspring/fruit.”

The expression also appears in funerary texts, where bodily “vital fluids” and functions are described as signs of strength and of the deceased person’s preserved vitality.

For example, in the Pyramid Texts (Pyramid of Pepi I, PT 493) it says:

“Air is in my nostril; seed is in my penis, like the ‘Mysterious Form’ that is among the radiance of light.”

ꜥr.t [aret] — buttocks; rear; sometimes: anus

The word denotes the back part of the body — “the rear/buttocks,” more rarely “the anus.”

In the Pyramid Texts, within the tradition about the conflict of Horus and Seth, one finds the formulation:

“Horus put his semen in Seth’s rear;

Seth put his semen in Horus’s rear.”

We have a separate article on this episode; all explanations are given there.

👉 Divine Homosexuality in the Ancient Egyptian Myth of Horus and Seth

pḥ.wyt [pekhuït] — anus

The word means “anus” and can also be used in the sense of “rectum.” In tone it often feels more “medical,” though it is not limited strictly to medical texts.

For example, it appears in the Hearst Papyrus (a medical collection), with passages such as “Remedy for the anus when it hurts” and “Remedy for cooling the anus.”

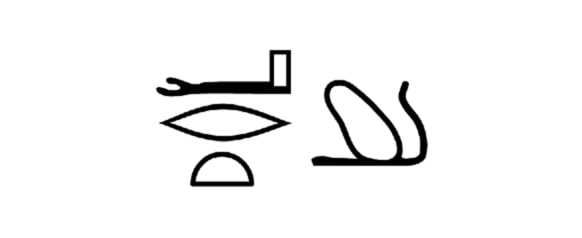

ḫpd [kheped] — buttocks

Another word meaning “buttocks,” “rear,” “the back part of the body.”

It appears in Middle Kingdom literary texts. In the same Story of Horus and Seth, the word ḫpd is used in a concrete, physical context: “If he used force against you, you should clamp your fingers between the buttocks.” Here ḫpd clearly refers to an anatomical body part — without euphemism or metaphor.

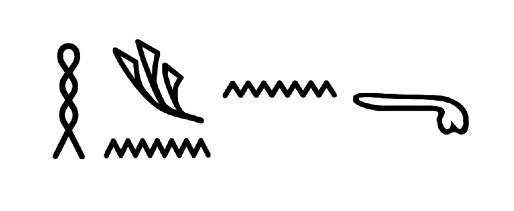

ḥm.tj [khemti] — a slur for an effeminate person or a coward

This is an insulting term that literally means “one who turns his back.” The ending -tj is a nominal suffix; it is not directly related to the word hmt “woman.” Yet a play on homonymy was apparently clear to speakers: the enemy is described both as “like a woman” and as “one who turns away/shows his back.” This layering strengthens the contemptuous tone.

The term is attested in magical texts, in particular within the corpus often called the “Magical Papyri.” One line reads, word for word: “You have unlawfully defiled an effeminate one on the fiery hill of Hetepet.”

ḥm.t-ẖrd [khemet-khered] — “woman-boy”

This is said of a youth described as effeminate and as someone who takes a “female” social-gender role in sex.

The expression appears in the 32nd maxim of Ptahhotep, part of his teachings — an Ancient Egyptian “school of wisdom,” where advice is given in short admonitions.

In this maxim the teacher warns: “Do not enter into nk (intercourse) with a ḥm.t-ẖrd, for you know that what people resist will become for him like water upon the chest… Let him cool down by destroying his desire.”

Here ḥm.t-ẖrd is understood as a youth in a “female” role, and his desire is depicted as obsessive and unable to find relief.

Sexuality in Ancient Egypt

The Ancient Egyptian language had no word that precisely matches the modern concept “homosexual.” Apparently, there was also no idea of “sexuality” as a basic personal trait — something around which a stable identity is built.

Because of this, attempts to “find homosexuality” in Ancient Egypt can easily become anachronistic. We risk projecting today’s categories backward and reading into the sources what they were never meant to convey. People described themselves and others differently—not in the terms or frameworks familiar to us — though same-sex desire certainly existed.

It is more useful to reconstruct Egyptian terms and Egyptian ways of speaking about experience, social norms, and their violations. But direct statements about sex are not common in the surviving texts.

First, the subject was considered indecorous: much was said indirectly — through euphemism, hints, jokes, and deliberate avoidance of explicit naming. Second, writing was the business of a minority. Many of the texts that reached us reflect an “official discourse” — what educated and powerful circles considered acceptable and worthwhile to put into writing.

Even so, vocabulary connected to same-sex practices did exist. Most often it clusters around penetrative acts and describes, above all, the act itself and the judgment attached to it. Such words frequently belong to a language of ethics, power, and humiliation: they surface in contexts of control and social hierarchy, rather than in a vocabulary of “love” as private feeling.

𓂸𓂸𓂸

🏺 This piece is part of the article series “LGBT History of Ancient Egypt”:

- A Queer Lexicon of Ancient Egypt

- Divine Homosexuality in the Ancient Egyptian Myth of Horus and Seth

- Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum: The First Same-Sex Couple in History

- A Homoerotic Plot in Ancient Egyptian Literature: Pharaoh Pepi II Neferkare and General Sasenet

- Idet and Ruiu: Lesbian Lovers in Ancient Egypt?

- A Possible Scene of Same-Sex Intercourse from Ancient Egypt — The Love Ostracon

- Goddess Nephthys — a lesbian?

𓂸𓂸𓂸

📣 Subscribe to our Telegram channel (in Russian): Urania. With Telegram Premium, you can translate posts in-app. Without it, many posts link to our website, where you can switch languages — most new articles are published in multiple languages from the start.

References and Sources

- Richard Parkinson: Homosexual Desire and Middle Kingdom Literature. In: The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology (JEA), vol. 81, 1995.

- Tags:

- Ancient-Egypt