Divine Homosexuality in the Ancient Egyptian Myth of Horus and Seth

“...how beautiful your buttocks are, how strong! Spread your legs,” Seth said to Horus.

- Editorial team

One of the earliest Egyptian myths describes a confrontation between the god Seth and his nephew Horus. In one episode, Seth seeks to assert superiority and humiliate Horus by forcing him into sexual intercourse. Horus responds with deliberate restraint: he catches Seth’s semen in his hand and discards it.

This plot may appear unexpected. Why would ancient priests include, within a religious narrative, a scene of male divine homosexuality? To address this question, it is necessary to clarify who these gods were, what their conflict concerned, and what symbolic meaning Egyptians attributed to actions of this kind.

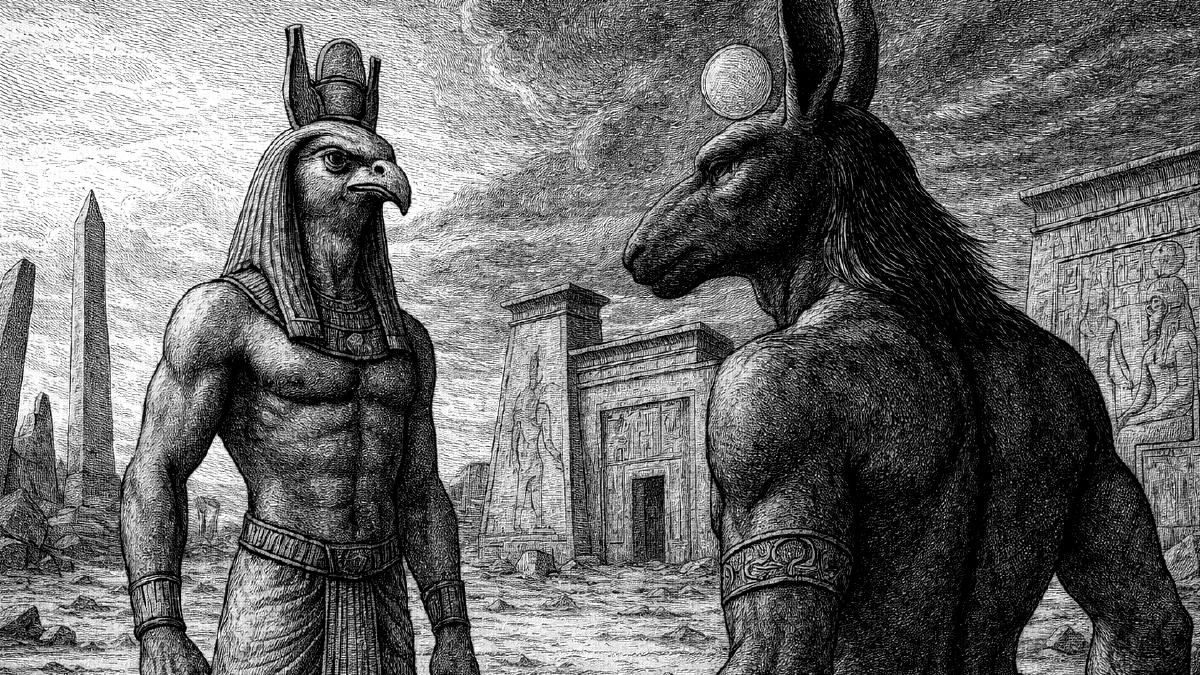

Who Horus and Seth Are

In ancient Egyptian tradition, Horus was depicted either as a falcon or as a man with the head of that bird. His name is commonly translated as “the exalted one” or “the distant one,” a sense linked to the falcon’s ability to rise high into the sky and, therefore, to Horus’s divine character. From early periods, his cult was closely associated with royal authority: pharaohs regarded Horus as their celestial patron.

According to myth, Horus was the son of Osiris and the nephew of Seth. His central aim became revenge for his father’s death. In the decisive contest, he defeated Seth and affirmed his right to the throne of Egypt.

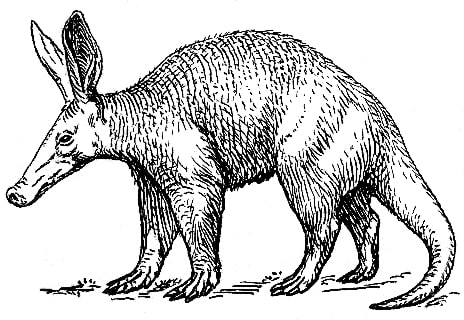

Seth likewise belonged to the oldest generation of Egyptian gods. He was depicted as a strange animal with an elongated snout and short ears. Scholars have suggested that the model for this creature may have been the aardvark.

In myth, Seth appears as an aggressive and cruel deity. He embodied chaos, destruction, the desert, and foreign lands — that is, everything beyond the fertile banks of the Nile.

Across different stories, Seth harasses goddesses and also attempts to subdue Horus in a homosexual sense — that is, as an act of domination and humiliation rather than mutual desire. For Egyptians, this behavior could be understood as a coherent expression of his nature: Seth personified a hostile element and an untamed force. At the same time, chaos was not treated as absolute evil; it was understood as a necessary component of the world order, without which balance is impossible.

In early texts, Seth is presented not as pure evil, but as a dangerous and cunning trickster. Over time, his image became darker: in later periods he was associated with foreigners and Egypt’s external enemies, and eventually he became a symbol of turmoil and destruction.

It is significant that ancient sources often present Horus and Seth together as a pair. They were called “the Two Lords,” “the Two Gods,” “the Two Men,” as well as “the Two Rivals” or “the Two Opponents.” These formulas express a central idea of Egyptian mythology: the world depends on the ongoing struggle between order and chaos, and it is precisely this tension that sustains equilibrium.

The History of the Myth “The Contendings of Horus and Seth”

The earliest versions of the myth describing the hostility between these gods date to Egypt’s Predynastic period — a time before the emergence of pharaohs or a unified state. In this early form, the legend includes only two figures, Horus and Seth. They are portrayed as irreconcilable rivals who repeatedly clash and inflict serious injuries on one another.

By the end of the Old Kingdom, the narrative gradually shifted. Priests introduced a new figure — Osiris. In the revised account, Osiris became Seth’s brother and was killed by Seth. After murdering Osiris, Seth also attempted to eliminate Osiris’s son, Horus, in order to claim supreme authority among the gods. This cycle of stories is commonly known as “The Contendings of Horus and Seth.” In other sources, it appears under several titles, including “The Dispute of Horus and Seth,” “The Duel,” and “The Lawsuit.”

The earliest written evidence of conflict between these deities appears in the Pyramid Texts — a collection of magical formulas and religious hymns carved on the walls of royal burial chambers at the very end of the Old Kingdom. Related motifs later occur in the Coffin Texts and in the Book of the Dead — a major corpus of spells intended to guide the deceased on the journey to the afterlife.

More developed versions of the myth took shape in the Middle Kingdom, beginning around 2040 BCE. The best-known redaction belongs to the end of the New Kingdom and is usually dated to about 1160 BCE. It is preserved in Chester Beatty Papyrus I, written in hieratic, a simplified and faster form of hieroglyphic writing used in everyday practice.

The papyrus was discovered in the village of Deir el-Medina, near ancient Thebes. The settlement was inhabited by artisans who produced tombs and paintings for pharaohs in the Valley of the Kings.

The translation and first publication of Chester Beatty Papyrus I were produced in 1931 by the British Egyptologist Alan Henderson Gardiner. The name of the ancient Egyptian author has not survived.

The Myth in Outline

The Greek writer Plutarch, who lived in the 2nd century CE, provides a detailed retelling of this story.

Osiris originally ruled Egypt as king. His brother Seth envied his power and devised a murder to seize the throne. He arranged a plot and invited Osiris to a banquet. There, Seth proposed that his brother lie down in an ornate chest made precisely to his measurements. As soon as Osiris lay inside, Seth slammed the lid shut and threw the chest into the waters of the Nile. In this way, Osiris perished.

His wife Isis set out to search for the body. When she found it and attempted to restore her husband to life, Seth intervened again: he stole the corpse, cut it into fourteen pieces, and scattered them across different parts of Egypt. Isis resumed her search and recovered nearly everything — except one part. According to Plutarch, the sexual organ could not be found, because fish had supposedly swallowed it. In Egyptian myths, however, another version is also attested: Isis managed to find all the parts. With the help of spells, she revived Osiris for a short time, and that was enough to conceive a son, Horus.

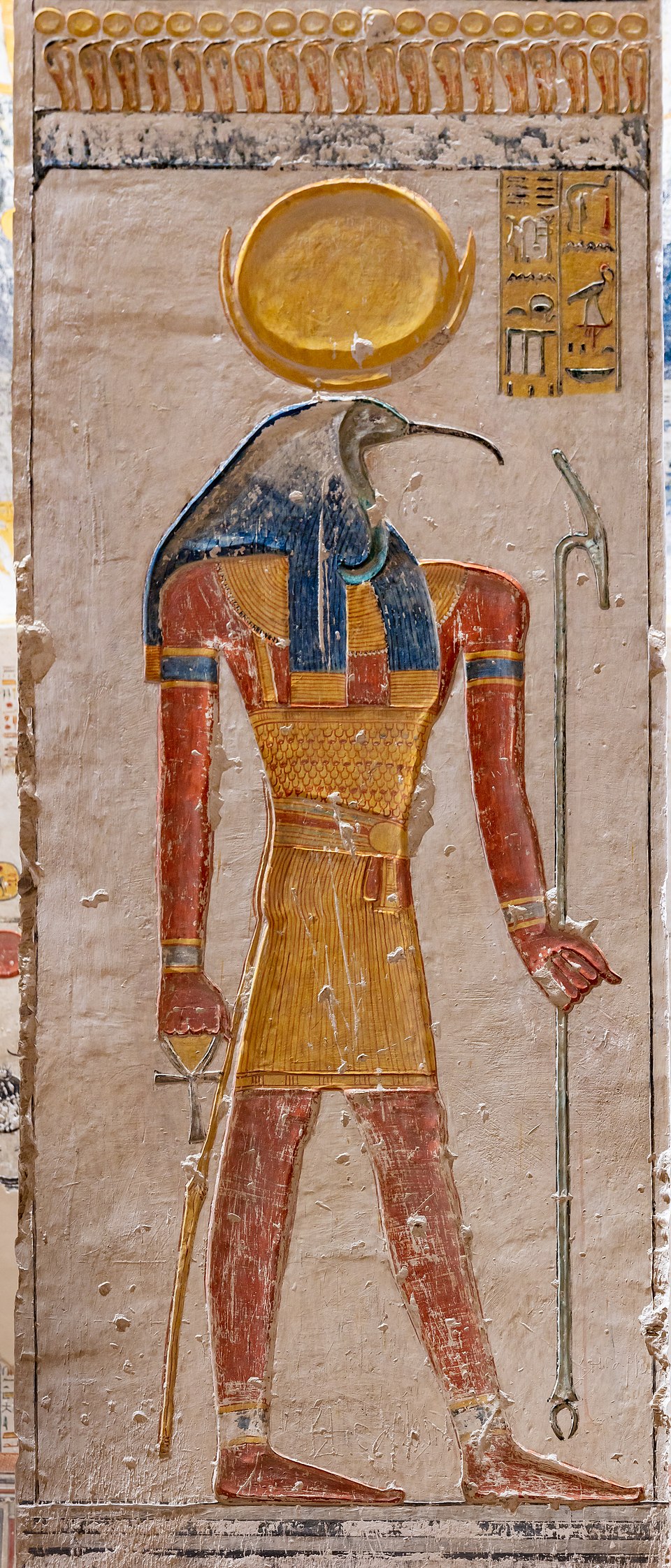

Horus was born weak, a premature child; tradition also says that his legs were sickly. From his earliest years, Seth tried to eliminate his nephew. In one tale, Horus nearly died from a scorpion sting, but the gods Ra, who personified the sun, and Thoth, regarded as the god of wisdom, saved him.

After Osiris’s death, the throne should have passed to Horus. Seth, however, insisted that the young god was too inexperienced to rule and demanded that he himself be recognized as king. At Isis’s request, the gods convened a court. Ra took the role of chief judge, and Thoth kept the record of the proceedings.

The dispute continued for eighty years: some supported Horus, others leaned toward Seth, and Ra himself most often sided with Seth. To settle the matter, they turned to the goddess of wisdom Neith. She issued the final verdict: by right, the throne belonged to Horus. At the same time, she attempted to appease Seth by promising him the goddesses Anat and Astarte as wives.

Even so, Ra continued to waver, and the sessions were postponed again and again. Seth demanded that Isis no longer take part in the process, and Ra agreed. Isis did not submit. She changed her appearance, bribed the ferryman Anty, and slipped into the courtroom. There, taking the form of a young woman, she seduced Seth, and he acknowledged her son’s right to the kingdom. When Isis revealed her true name, Seth was disgraced. The gods ruled that Horus should be crowned, and the guard Anti was punished for his betrayal.

Seth still had no intention of yielding. He proposed a new ordeal: both gods were to turn into hippopotamuses and hold their breath underwater in the Nile for three months. The victor would be the one who lasted longer. Horus and Seth dove in.

Isis, fearing for her son’s life, fashioned a magical spear and hurled it. She first struck Horus by accident, and then Seth. When Seth began to beg her for mercy, she took pity and pulled the spear out. Horus, outraged by his mother’s leniency, flew into a rage and beheaded her. In the same instant, Isis turned into a headless stone statue. The god Thoth restored her by attaching a cow’s head to her body.

Insulted, Horus left the assembly of the gods and withdrew into the desert. There, Seth caught up with him, tore out his eyes (in other versions — only the left one), and buried them in the ground. But the goddess Hathor took pity on Horus: she prepared a healing potion from antelope’s milk, and his sight returned, although the eyes themselves were never found.

Weary of the unending hostility, Ra demanded that Horus and Seth at least sit at the same banquet table. Seth, however, did not stop.

The Homosexual Episode of the Myth

Seth continued to prevent any reconciliation and made a new attempt to disgrace his nephew. He invited Horus to spend the night at his house, and Horus agreed. During the night, Seth attempted to rape him. In Egyptian culture, a scene of this kind was understood as an effort to humiliate a rival and deprive him of his right to rule.

Horus avoided the assault: he caught his uncle’s semen in his hands and brought it to his mother.

When Isis learned what had happened, she was horrified. To “purify” her son, she cut off his hands and threw them into the Nile, then restored them through magic. She then masturbated her son, collected his semen, and deceived Seth into “eating” it: she smeared it onto lettuce — the salad green he especially liked. Unaware of the trick, Seth ate the dish and became “pregnant” by Horus.

Later, a shining disk appeared on Seth’s forehead, like the moon. He tried to get rid of it, but Thoth, the god of wisdom, seized the disk and made it a symbol of the night luminary — the Moon.

Here Is How the Sources Describe It. In the Kahun Papyrus, written in the Middle Kingdom, Seth persuades Horus to spend the night with him and praises his backside. The historian Parkinson treats this passage as one of the earliest examples of flirtation:

“The Majesty of Seth said to the Majesty of Horus: how beautiful your buttocks are, how firm! … Spread your legs….

And the divine Horus said: ‘Be careful — I will tell about this!’”— Kahun Papyrus, dialogue of Seth and Horus

After this exchange, Horus complained to his mother about Seth’s advances, and Isis advised him on how to avoid violence while also preserving Seth’s semen.

“And she said to him: ‘Watch out! Do not raise this matter with him! When he speaks of it again, then say to him: “It is too painful for me, because you are heavier than I am. My strength — my backside — cannot endure your strength — your erection….” When he gives you his strength, place your fingers between your buttocks. … Then he will feel great pleasure. Keep the semen that comes out, and do not let the sun see it…’”

— Kahun Papyrus, dialogue of Seth and Horus

She then smeared Horus’s semen onto Seth’s favorite lettuce (a kind of salad greens). When Seth, confident of his success, began boasting before the gods that he had taken his nephew, the gods decided to test both of them.

At their summons, Seth’s seed responded from the water, while Horus’s seed appeared on Seth’s forehead as a golden disk. Thoth took this sign for himself and made it a symbol of the moon.

Another source is the Pyramid Texts, dating from the end of the Fifth Dynasty and throughout the Sixth Dynasty. This passage was published only in 2001, after it was discovered in the pyramid of Pharaoh Pepi I. There, Seth and Horus are presented as equal partners in a sexual act, with both taking an active role:

“If Horus put his seed into Seth’s anus, that is because Seth put his seed into Horus’s anus!”

— Pyramid Texts, Fifth Dynasty

A later version of the myth dates to the New Kingdom, to the end of the Twentieth Dynasty, around 1160 BCE. In this account, the events unfold somewhat differently:

“Seth said to Horus, ‘Come, let us spend a pleasant hour in my house.’

Horus replied, ‘With pleasure, with pleasure.’

When evening came, a bed was made for them, and they lay down. In the night Seth stiffened his penis and placed it between Horus’s thighs. Horus put his hands between his thighs and caught Seth’s semen.”— Later version of the myth, New Kingdom (end of the Twentieth Dynasty)

After this, Horus went to his mother and showed her the semen:

“Help me! Come — look at what Seth has done to me.” And he opened his palm and showed her Seth’s semen. With a cry, she took a weapon, cut off his hand, and threw it into the water; then, with the help of a spell, she made him a new hand in its place. Next Isis helped Horus expel the semen and smeared it onto lettuce — Seth’s favorite vegetable — and then gave it to him to eat.

— A later version of the myth, the New Kingdom (late Twentieth Dynasty)

When Seth appeared before the council of the nine supreme gods — the Ennead (a group of nine principal deities) — he claimed that he had taken Horus and performed “the deed of a man [a warrior]” (that is, an act of sexual domination intended to humiliate). The gods reacted with outrage: they shouted, spat in Horus’s face, and openly condemned what they had heard.

Soon, however, the scene repeated itself. The gods again summoned the semen — and the deception became clear.

At the end of the myth, Osiris intervened, having remained silent until that point. He accused the gods of weakness and threatened to send famine and disease upon Egypt from the underworld unless they recognized Horus’s rights. Alarmed by this threat, the gods ruled in Horus’s favor and acknowledged him as the legitimate heir to royal authority.

At the same time, Seth was not rejected. He was placed beside the sun god Ra and called “he who roars in the sky.” From that moment, Seth was assigned a stable role as a god of storm and thunder — feared, yet revered.

Interpretations of Homosexuality in the Myth

For a long time, academic scholarship treated the episode of Seth’s homosexual assault on Horus as comic and even obscene. The Egyptologist and translator Alan Henderson Gardiner described it as an instance of “frivolous literature.” His strict, puritan outlook prevented him from taking narratives of violence and eroticism seriously: the beheading of Isis, Horus’s mutilations, injuries to the eyes, and Seth’s homoerotic behavior were, in his view, relegated to texts of doubtful value, supposedly read to peasants at memorial rites.

Later, alternative interpretations emerged. Henri Frankfort and Adriaan de Buck understood the myth as an expression of the dualism at the core of the Egyptian worldview. For Egyptians, reality consisted of complementary opposites: male and female, sky and earth, order and chaos. Horus and Seth embodied these forces, and their struggle represented an eternal clash in which order ultimately prevailed and Horus affirmed his dominance.

In 1967, Herman te Velde, in his monograph Seth, God of Confusion, proposed a more complex account. He traced the myth to deep antiquity, when religious concepts and rituals were taking shape. In his view, Horus personified royal order, while Seth represented instability, rage, and madness. Seth’s sexual desires shifted between men and women, and his testicles (sexual energy) signified destructive cosmic forces and social upheaval. Horus’s victory did not eliminate Seth permanently: their union expressed the harmony of opposites, and the pharaoh was understood as a figure who contained and unified them.

Wolfhart Westendorf offered a different reading. He argued that Egyptians considered semen to be poisonous if it entered the body “in an improper way.” Yet Seth, who ingested the semen with lettuce, survived. In this episode, the decisive point was to demonstrate that whoever occupies the “female” role in a sexual act cannot claim royal power.

Dominic Montserrat approached the myth from another angle and stressed the opponents’ equality: they are adult gods of the same rank. Horus accepts intimacy but avoids anal intercourse, while Seth openly displays desire. This allows the tentative conclusion that male desire for another man was not necessarily prohibited in Egypt; however, anal submission itself was treated as disgrace. Such relationships were known and could be practiced, but relative status within them was decisive.

A particular role is played by the lettuce onto which Isis poured her son’s semen. In Egyptian culture, this plant symbolized male fertility. Through the lettuce, Seth is symbolically “impregnated” and, in a sense, feminized, which ultimately deprives him of the right to supreme power.

At the same time, the myth preserves internal tensions: for Horus, the prospect of being “submissive” was shameful, yet it was precisely his semen inside Seth that produced the divine symbol of the moon.

The Symbolism of Power in the Myth

From an early period, the myth of the struggle between Horus and Seth was associated with the concept of royal authority in Egypt. The German Egyptologist Kurt Heinrich Sethe argued that the legend reflected a conflict between Upper and Lower Egypt. More recent scholarship, however, tends to interpret it not as a confrontation between the two halves of the country, but as an older rivalry between the cities of Nekhen and Nubt.

Archaeological evidence suggests that by around 3500 BCE the inhabitants of these centers revered Horus and Seth as their principal patrons. Nekhen’s victory shifted the political balance: its rulers brought Egypt under their control and presented the country as being under Horus’s protection. The earliest kings began to incorporate the god’s name into their titles: rulers are attested as Hor (Horus), Ni-Hor, Hat-Hor, Pe-Hor, and others.

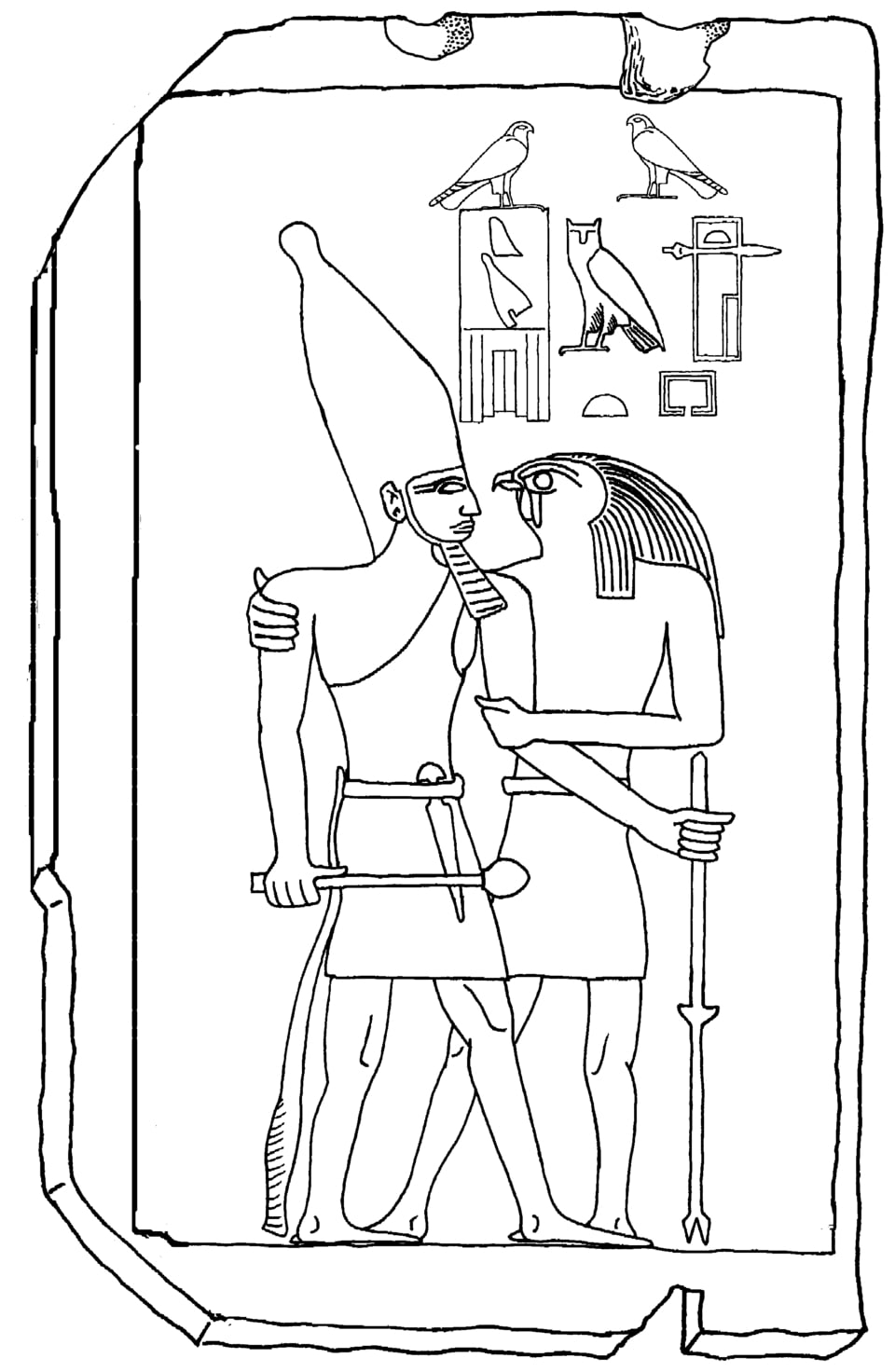

Over time, Egyptians came to understand the country as a single entity composed of the “Two Lands” — Upper and Lower Egypt. The emblem of this unification was the pharaoh’s crown, the Pschent (the double crown; from Egyptian pꜣ-sḫm.ty (Pa-sekhemty), “the Two Powerful Ones”), which joined the white and red crowns. Within this framework, the king could be represented as the embodiment of the “Two Fighters” — Horus of Nekhen and Seth of Nubt.

This pairing expressed a ritual unity of opposing forces. As early as the First Dynasty, the title “Horus – Seth” appeared. In this duo, Horus represented order and harmony, while Seth represented destructive energy directed against Egypt’s enemies.

The Symbolism of the Eye of Horus and the Testicles of Seth

In ancient Egyptian myth, light and sexuality were often framed as opposing forces. This polarity appears in early sources through two emblematic images: the Eye of Horus and the Testicles of Seth. When one of these symbols was emphasized, the other, in a certain sense, was pushed into the background.

The Eye of Horus was associated with the moon and its changing phases. Within priestly tradition, it signified light, restoration, and continuous renewal. In contrast, Seth’s testicles were understood as a marker of chaotic and unrestrained sexuality, and more broadly of human passions and desires. This energy was considered beneficial only when strictly controlled and subordinated to order.

More generally, Seth’s image remained ambivalent and unstable. Mythic narratives attribute to him desire for both women and men. His testicles were linked to destructive natural forces — thunder, hurricanes, and storms. They also functioned as a metaphor for social disruption: eruptions of rage, violence, and collective crisis.

Several of these motifs appear in the Pyramid Texts:

“When no fury had yet arisen.

When no cry had yet arisen.

When no quarrel had yet arisen.

When no turmoil had yet arisen.

When the Eye of Horus had not yet turned yellow.

When the testicles of Seth had not yet become powerless.”— The Pyramid Texts

“Horus fell because of his eye; Seth suffered because of his testicles.”

— The Pyramid Texts

“Horus fell because of his eye; the Bull disappeared because of his testicles.”

— The Pyramid Texts

“… so that Horus may be purified of what his brother Seth did to him,

and so that Seth may be purified of what his brother Horus did to him.”— The Pyramid Texts

The God Thoth – Son of Horus and Seth

In ancient Egyptian ideas, the appearance of the Moon was linked to myths about Horus, Seth, and Thoth. According to one version, the lunar disk arose from Seth’s forehead. This happened after he swallowed lettuce soaked with Horus’s semen. The semen flared up and turned into a golden disk shining on his head. Enraged, Seth tried to tear the disk off, but Thoth, the god of wisdom, took it and placed it on his own head as a crown.

A similar motif already appears in the Pyramid Texts. There it was claimed that Thoth came from Seth, or that the Moon was taken directly from this god’s forehead. Later, in the Coffin Texts, Thoth addresses Osiris and calls himself “the son of his son, the seed of his seed.” This formula emphasized Thoth’s origin from Horus and made him Osiris’s grandson.

In other sources, Thoth is called “the son of the Two Rivals” or “the son of the Two Lords, who came forth from the forehead.” This unusual birth was understood as a sign of reconciliation: Thoth turned out to be the son of two gods at once and was therefore seen as a mediator capable of ending their eternal feud.

There was also another version of the myth. In it, during the duel Seth tears out both of Horus’s eyes, or only the left one. The eye thrown to the ground shatters into six pieces. Thoth gathers them, heals them, and returns them to Horus. This episode had a sacred meaning: it restored the cosmic order disrupted by the struggle. Harmony returned only when Horus regained his eye and Seth made up for his lost strength. The Pyramid Texts put it like this:

“The bearers of Horus, who loved Teti, for he brought him his Eye! The bearer of Seth, who loved Teti, for he brought him his testicles! The bearer of Thoth, who loves Teti! Because of them the Double Ennead trembled! But the bearers whom Teti loves — they are the bearers to the offering table!”

— The Pyramid Texts

Horus and Seth in the Tomb of an Ancient Egyptian Same-Sex Couple

The story of the confrontation between Horus and Seth is found not only in papyri, but also in the wall paintings of Egyptian burials. One revealing example survives in the tomb of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep. These men lived in the time of Ancient Egypt and entered history as the first known same-sex couple.

👉 Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum: the first same-sex couple in history.

On one wall of the tomb, Khnumhotep is shown holding a lotus; nearby there is a scene with musicians. The choir leader turns to three singers and two harpists and says: “Play the one about ‘the Two Divine Brothers.’”

Researchers suggest that, at a banquet held in honor of these men, a song connected with the myth of the struggle between Horus and Seth was performed. Such texts were often strikingly blunt — and sometimes outright coarse — so it is likely that this piece functioned as an entertaining number at the festive gatherings of the elite.

🏺 This piece is part of the article series “LGBT History of Ancient Egypt”:

- A Queer Lexicon of Ancient Egypt

- Divine Homosexuality in the Ancient Egyptian Myth of Horus and Seth

- Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum: The First Same-Sex Couple in History

- A Homoerotic Plot in Ancient Egyptian Literature: Pharaoh Pepi II Neferkare and General Sasenet

- Idet and Ruiu: Lesbian Lovers in Ancient Egypt?

- A Possible Scene of Same-Sex Intercourse from Ancient Egypt — The Love Ostracon

- Goddess Nephthys — a lesbian?

📣 Subscribe to our Telegram channel (in Russian): Urania. With Telegram Premium, you can translate posts in-app. Without it, many posts link to our website, where you can switch languages — most new articles are published in multiple languages from the start.

References and Sources

- Assmann J. Mort et au-delà dans l’Égypte ancienne, 2003. [Assmann J. - Death and the Afterlife in Ancient Egypt]

- Broze M. Mythe et roman en Égypte ancienne. Les aventures d’Horus et Seth dans le Papyrus Chester Beatty I, 1996. [Broze, M. - Myth and Novel in Ancient Egypt: The Adventures of Horus and Seth in Papyrus Chester Beatty I]

- Gerig B. L. Homosexuality and the Bible.

- Reeder G. Same-Sex Desire, Conjugal Constructs, and the Tomb of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep, World Archaeology, 2000.

- Tags:

- Ancient-Egypt