A 4,600-Year-Old Burial of a “Third-Gender” Person: What We Know and What Is Disputed

An ancient burial discovered in Prague in which a man was buried according to a female funerary rite.

- Editorial team

In 2011, Czech archaeologists in Prague discovered an unusual burial. In the press, it was presented as “the oldest burial of a third-gender person.”

The find was dated to the Eneolithic period—roughly 2800–2500 BCE.

The skeleton belonged to a man, but the burial rite itself looked atypical for this tradition. In the culture to which the grave was assigned, people usually followed clear rules: men were buried on their right side, and women on their left. The orientation of the body and the position of the head also differed.

In the Prague case, the man was laid out “in the female manner.” Nearby were objects that more often appear in women’s burials. Because of this, researchers suggested that he may have held a special position in the community—for example, that he belonged to people whose social gender role did not match customary expectations.

Major Czech media outlets reported the story as evidence that a “third gender” existed in prehistoric society. At the same time, some archaeologists disagreed with that interpretation.

Dating and Cultural Context

The Eneolithic, or Copper Age, is a transitional period between the Neolithic and the Bronze Age. Copper was already widely used, but bronze had not yet become the standard material for tools and weapons. The Prague burial is attributed to this period and to the Corded Ware culture.

An archaeological culture is not a “people” and not a state. It is a conventional term archaeologists use to group ancient sites and finds by similarities in objects, technologies, and burial rules.

Corded Ware culture was named after a characteristic decoration on pottery. A cord was pressed into wet clay, leaving impressions on the surface that look like twisted string. The culture’s distribution was very broad: from Northern and Central Europe to areas stretching between the Rhine and the Volga.

This tradition is known for stable burial rules. People usually repeated a recognizable set of actions: how the body was placed, which direction the head faced, and what items were put into the grave. In Corded Ware burials, differences between men and women are often visible. Men are typically found lying on their right side, with the head oriented to the east. Women are typically found on their left side, with the head oriented to the west.

What the Burial Looked Like

The grave was found on Terronská Street in the Prague 6 district. Inside lay an adult. Based on the bones, the individual was identified as male: in archaeology, sex is most often determined from the shape of the pelvis and a set of features on the skull.

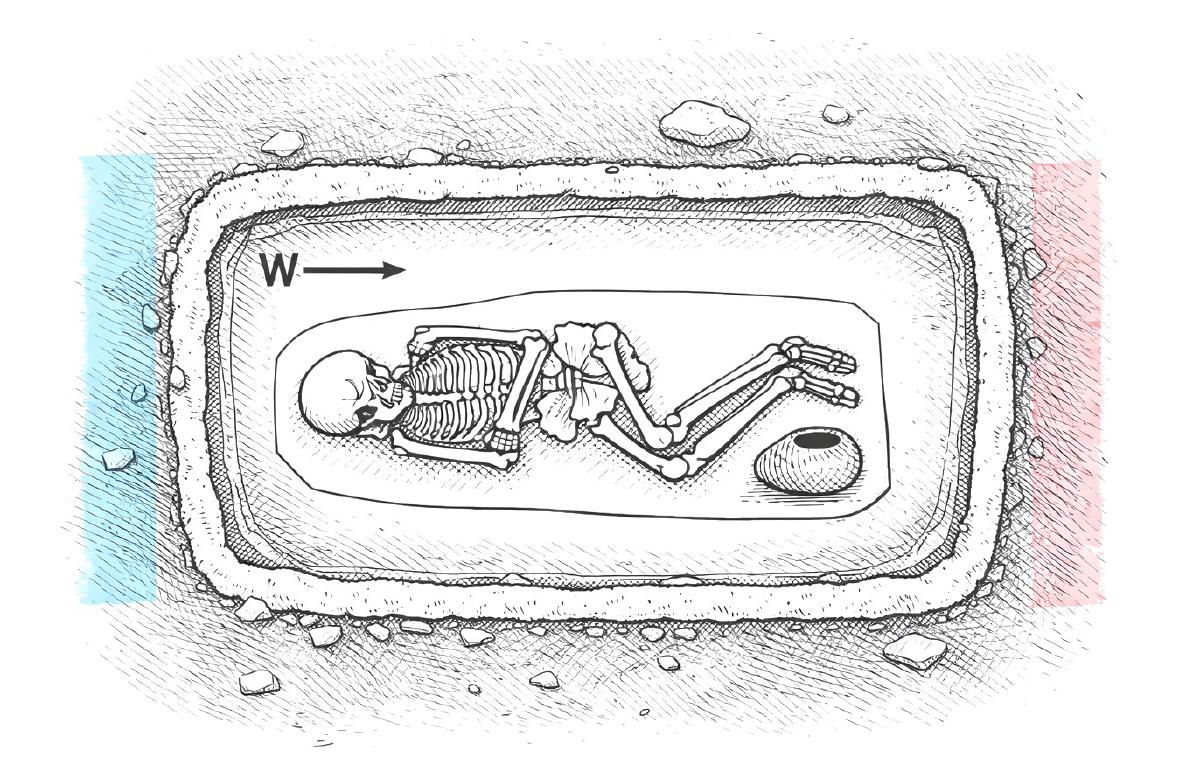

The skeleton lay on its left side, with the head facing west. Researchers classified this combination of traits as the “female” version of the rite. Near the feet stood an oval, egg-shaped vessel—forms that are also more often associated with “female” burials.

At the same time, the grave lacked items that typically accompany “male” burials: weapons, stone battle-axes, flint knives, and other objects of the same kind.

It was precisely this combination—a male skeleton together with ritual features interpreted as “female”—that became the basis for the phrase “third gender.”

The “Pro” Arguments: Why People Started Talking about a “Third Gender”

In 2011, the head of the research team, Kamila Remešová, presented the main argument at a press conference: in societies with a strictly regulated funerary ritual, such “mistakes” are usually not allowed. If the community truly followed a stable template, then the combination of a male skeleton with “female” ritual markers looks less like an accident and more like a deliberate decision by those who performed the burial.

From this comes the inference: if a person is biologically male but buried according to a “female” rite, that may indicate that, socially, he occupied an intermediate position—“neither male nor female.”

Archaeologist Kateřina Šemrádová was even more direct in an interview with Czech Position: in her words, this could be one of the earliest cases in the Czech lands of what might be described as the burial of a “transsexual” person or a “third-gender” person.

Scholars also point to ethnographic parallels. In older literature, for example, one finds the term berdache: it was used for people in some Indigenous North American societies who held distinctive social and ritual roles and did not fit neatly into a simple “man/woman” scheme.

Why This Is Not “Proof”

Even if the parallels sound persuasive, the method has clear limits. Body position, orientation, and the set of grave goods are not direct markers of modern self-identification. Archaeology primarily records how the living “presented” the dead through ritual. So even if the community really did code this person as someone who did not fit a binary norm, it remains unclear what, exactly, that signal meant: a social role, a special status, bodily traits, a life story, a ritual function—or something else. We can see a sign, but we cannot automatically attach a modern meaning to it.

Gender roles in prehistoric communities are generally difficult to reconstruct with confidence. The sources are scarce, and they rarely allow us to recover exactly how roles and statuses were distributed. A single “anomaly” is not enough to automatically translate archaeological observations into “transgender identity” in today’s sense.

Some Czech archaeologists emphasize that even the presence of strict burial norms does not mean they functioned as an iron rule with no exceptions. Variations occur even within a single culture, and comparative material from another burial at Ruzyně suggests that “rules” could overlap. There, a male grave contained a mug of a type considered “female.”

Moreover, the man at Ruzyně was buried alongside a child, and some researchers allow that the Terronská Street grave may also have contained another individual—a child whose skeleton did not survive or was lost. In that case, the “female” items could have belonged to the child rather than to the adult.

Another line of dispute concerns the preservation of the grave itself. Skeptics argue that the pottery may have ended up in the pit fill in a different position than it had at the time of burial: it could have shifted later. The upper parts of the burial may have been destroyed, and the soil disturbed.

For rescue excavations in a city, this is a common situation: sites are often damaged by construction, utilities, and other later interventions. That kind of explanation may apply to objects, but it does not fully resolve the question of the adult skeleton’s position and orientation.

There is also a different way to read the evidence: posture and orientation could reflect a local custom within the region, a one-off decision by the community, an attempt to highlight status or group affiliation, or other social signals. Sometimes the circumstances of death can influence the ritual and alter the usual burial pattern.

Related to this are age- and role-based factors and the intersection of different categories. Modern overviews in gender archaeology remind us that a simple “male/female” scheme does a poor job of describing, for example, child and elderly burials. It also fails to capture the fact that a person’s social roles could change over the course of life.

Czech scholars have also noted that the race for sensational headlines can damage archaeology’s reputation: the public remembers the loud version, not the hypotheses and methodological limits that researchers insist on.

***

The Prague burial really does stand out, and that alone makes it important. At minimum, it shows that the ritual recorded not only “the norm” but also exceptions: the community noticed differences and sometimes marked them in funerary practice.

This find can be included in LGBT history, but cautiously—as a trace of ancient gender otherness and role nonconformity. Its value is that it reminds us: human diversity did not appear in the 20th or 21st century. It has always existed, including in prehistoric times.

🦴 This piece is part of the article series “Prehistoric LGBT History”:

- Homosexuality Among Neanderthals

- The First Homoerotic Image in History — The Addaura Cave Rock Engravings

- A Prehistoric Double Phallus From the Enfer Gorge

- A Homosexual Scene in Norway’s Prehistoric Art: The Bardal Petroglyphs

- A 4,600-Year-Old Burial of a “Third-Gender” Person: What We Know and What Is Disputed

📣 Subscribe to our Telegram channel (in Russian): Urania. With Telegram Premium, you can translate posts in-app. Without it, many posts link to our website, where you can switch languages — most new articles are published in multiple languages from the start.

References and Sources

- Výbor SAS. Stretnutie slovenských archeológov a Výročná členská schôdza SAS. (Informátor). 2011. [SAS Committee - Meeting of Slovak Archaeologists and the SAS Annual General Meeting (Newsletter/Informátor)]

- Gaydarska B., Rebay-Salisbury K., Ramírez Valiente P., et al. To Gender or not To Gender? Exploring Gender Variations through Time and Space. (European Journal of Archaeology). 2023.

- Petriščáková K., Šmolíková M. Pohřby kultury se šňůrovou keramikou z Prahy-Ruzyně. (Praehistorica). 2019. [Petriščáková, K.; Šmolíková, M. - Burials of the Corded Ware Culture from Prague–Ruzyně]

- Mikešová Puhačová V. Archeologie a veřejnost – vztah vědního oboru a laické veřejnosti. 2012. [Mikešová Puhačová, V. - Archaeology and the Public: The Relationship Between the Discipline and the Lay Public]