Sergei Romanov: A Homosexual Member of the Imperial Family

The life of Grand Duke – a “white marriage” without children, homosexuality, service in Moscow, and a tragic death.

- Editorial team

In the Romanov dynasty (Russia’s ruling imperial family from 1613 to 1917), every adult family member was expected to marry and produce heirs — this was seen as part of one’s duty to both the family and the state. Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich (a “Grand Duke” was a high-ranking title reserved for close male relatives of the Russian emperor), the brother of Emperor Alexander III, also married, but the couple never had children. The Grand Duke was homosexual.

The main source of information about Sergei Alexandrovich is considered to be his personal diary, which he kept for many years. In these entries, Sergei Alexandrovich comes across as a man with a vivid personality, intense emotions, and firm convictions.

This article will discuss his life, how his homosexuality affected his fate, and his place in history.

Childhood, Education, and Coming of Age

Sergei Alexandrovich Romanov was born on May 11, 1857, in Tsarskoye Selo (literally “Tsar’s Village,” an imperial residence town near Saint Petersburg). Today, it is the town of Pushkin. He was the sixth child and the fifth son of Emperor Alexander II — the ruler under whom major reforms began in Russia — and Empress Maria Alexandrovna.

From childhood, Sergei received an excellent education. He was taught by some of the strongest teachers of his time. Among them was Anna Tyutcheva — the daughter of the poet Fyodor Tyutchev. Sergei read a great deal, especially loved history and culture, and even sometimes spoke with the writer Fyodor Dostoevsky.

The emperor’s children were raised strictly. They could not freely walk around or play with other children. At the same time, they grew up in palace luxury — creating a strange combination: outwardly everything was rich, but inwardly there were many restrictions.

Because of this isolation, it was harder for them to “grow up” in a real, practical sense. For example, at fifteen Sergei played with porcelain pugs. And on the day of his eighteenth birthday, together with his cousin Konstantin (known as K.R. — a pen name used by Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich, who was also homosexual), he blew soap bubbles. Later Sergei recalled that day with irony, surprised by his own childishness.

As he grew older, Sergei became an intelligent and well-mannered man. During a trip to Italy he spoke with Pope Leo XIII. According to eyewitnesses, in one dispute about church history it was Sergei who turned out to be right.

True inner maturity came to him during war. In 1877, the Russo-Turkish War began: Russia fought the Ottoman Empire and supported the push for independence by Romania, Serbia, and Montenegro. Twenty-year-old Sergei went to the front. In the war he showed bravery and received the St. George Cross, 4th class (a high military decoration in Imperial Russia awarded for personal courage).

Sergei loved wild strawberries, Crimean wines, and valued sapphires especially highly. At the same time, when traveling in Europe he did not idealize “the West.” In England, where he was in 1875, Sergei wrote that the local way of life seemed too down-to-earth: the English, in his words, thought mainly about comfort, food, and sleep, rather than spiritual and cultural aims.

“I would rather be a thousand times a simple mortal than a Grand Duke.”

— Sergei Alexandrovich Romanov

By temperament, Sergei was an introvert (someone who tends to focus inward, needing solitude and processing feelings privately). His cousin Konstantin (K.R.) wrote that Sergei “never, or only with great difficulty, cries; he endures his grief in silence and does not speak out.”

The historian M. M. Bogoslovsky called him “very shy.” Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna the Younger noted that Sergei was not only shy but also reserved: he did not like showing emotions and avoided frank conversations. This can be connected to the fact that Sergei was homosexual. In his position — within the imperial family and in a society where one could not live openly — such a private life almost inevitably required constant caution and silence, which in turn reinforced withdrawal.

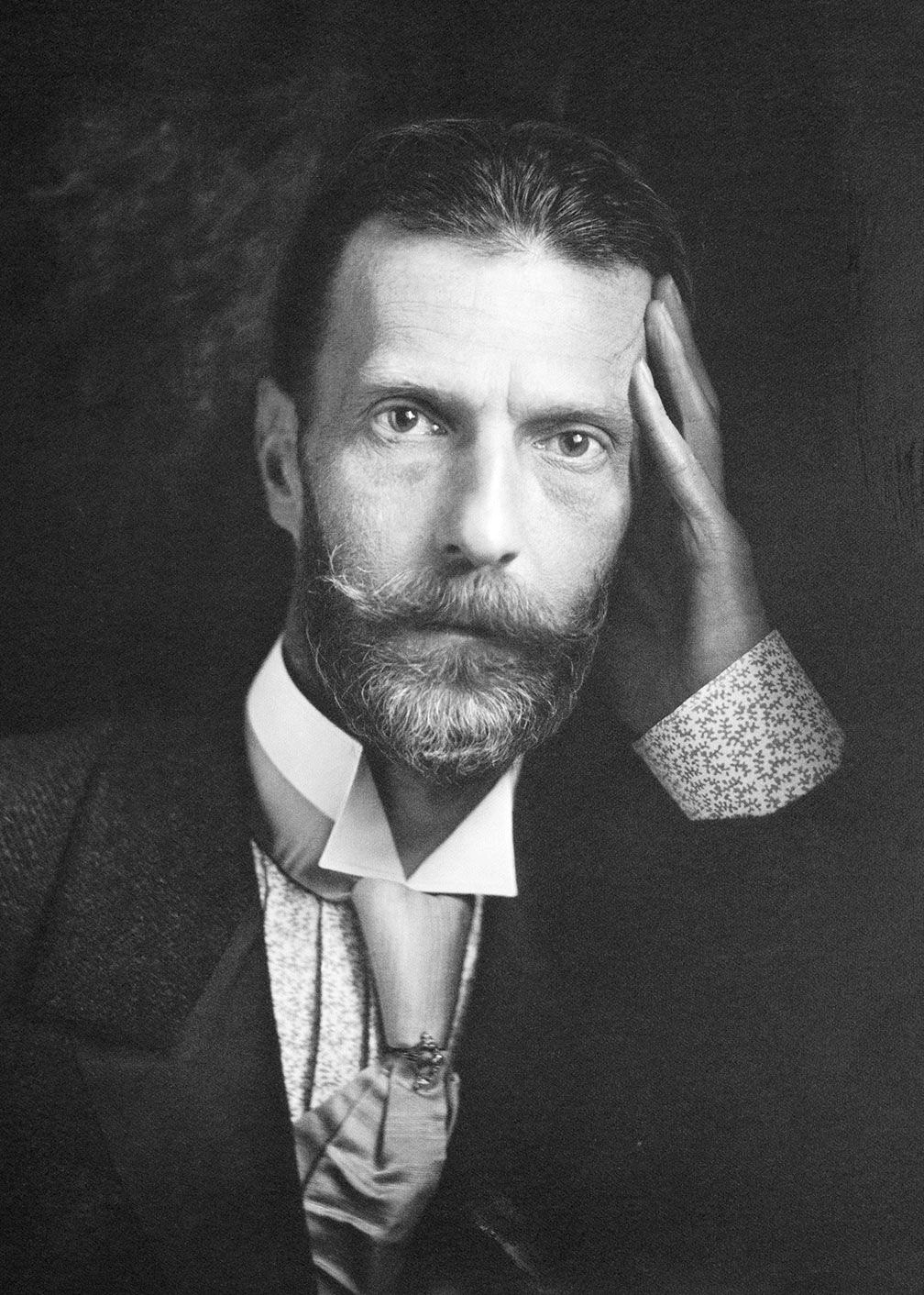

“Very tall, strikingly aristocratic-looking and extremely elegant, he gave the impression of an exceptionally cold man.”

- — General Alexander Mosolov, on Sergei Alexandrovich Romanov’s appearance*

In 1880 Sergei lost his mother, and a year later — his father. Emperor Alexander II was killed by revolutionaries: a bomb was thrown at him.

“I ask myself, how can one live through all this?”

- — Sergei Alexandrovich Romanov*

After this tragedy, Sergei went on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land — to Palestine (in Christian usage, “the Holy Land” means places associated with the life and preaching of Jesus Christ).

The trip deeply affected Sergei. After returning, he founded the Imperial Orthodox Palestine Society. This organization built schools and shelters for pilgrims, helped people with housing, food, and medical care. Thanks to such support, a trip to Palestine became possible not only for the rich but also for more ordinary people from the Russian Empire.

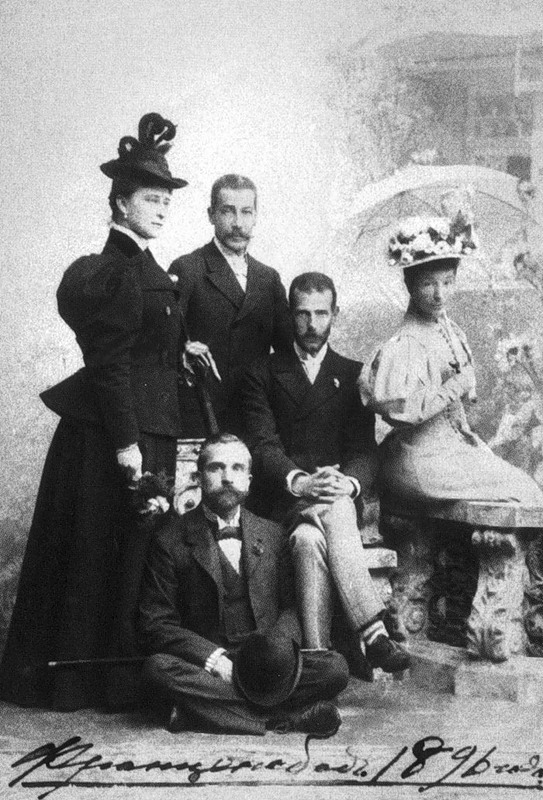

To a large extent, Sergei was saved from his severe emotional state by his future wife — Elizaveta Fyodorovna. She was a German princess from the House of Hesse-Darmstadt (a ruling dynasty in one of the German states) and also a granddaughter of Britain’s Queen Victoria.

The future German Kaiser (the German word for “emperor”) Wilhelm II pursued her, but her father chose a marriage for his daughter with a Russian Grand Duke. Elizaveta became for Sergei not only a wife but also a close friend. Seven years after the wedding she voluntarily adopted Orthodoxy — and this was her personal choice; formally, no one required it of her.

“Let people shout about me, but only never say a word against my Sergei. Take his side before them and tell them that I adore him, and also my new country, and that in this way I learned to love their religion too…”

- — Elizaveta Fyodorovna, in a letter to her brother about her new life*

The Grand Duke’s Homosexuality

Judging by many accounts, Sergei and Elizaveta’s relationship was more friendly than romantic. They never had children.

Contemporaries and historians wrote that this marriage was hard for Elizaveta. In public she tried to look calm and satisfied, but privately she suffered.

“Their married life did not work out, although Elizaveta Fyodorovna carefully concealed this, not admitting it even to her Darmstadt relatives. One reason for this, among others, was Sergei Alexandrovich’s attraction to people of the same sex.”

— Historian Voldemar Balyazin

At the same time, surviving letters show that there was respect and warm affection between the spouses. They cared about each other and behaved like close people, but there seems to have been no marital relationship in the usual sense. Sergei wrote to Elizaveta very tenderly:

“I am enchanted at the thought of seeing you tomorrow. I kiss you very tenderly.”

— Sergei Alexandrovich Romanov, in a letter to Elizaveta

The Russian Orthodox Church explained their childlessness differently. According to the Church version, even before the wedding Sergei and Elizaveta took a vow of chastity — a promise to live without physical intimacy. Such a union was called a “white marriage”: the spouses lived together, but their relationship was supposed to be like that of brother and sister.

The writer Nina Berberova, speaking about the composer Pyotr Tchaikovsky (who was also homosexual), described how people like this were treated at the top of the Russian Empire. The law at the time included an article punishing male same-sex intercourse, but aristocrats were usually not brought to court. More often the response was softer and quieter: the person would be pushed away from the capital — sent to the provinces, appointed to a post “off to the side,” or given the chance to leave for a long trip.

Berberova gave an example in which it was not the Grand Duke himself who suffered, but his alleged partner — a teacher of classical languages:

“One case is known involving a man familiar to quite a few people, a teacher of Latin and Greek, the lover of the Moscow governor, Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich, who was tried and given three years of ‘exile’ to Saratov, and then returned to Moscow.”

— Writer Nina Berberova

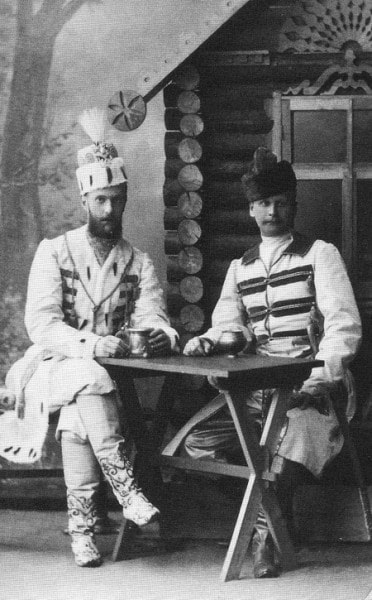

Sergei Alexandrovich belonged to the very highest layer of the empire and, according to memoirs, did not hide his special attention to young officers — especially to aides-de-camp. An aide-de-camp is an officer assigned as a personal assistant to a high-ranking commander: he accompanies the superior, carries out assignments, and helps with official duties.

In many photographs, Sergei is pictured next to his aide-de-camp Konstantin Balyasny, who often accompanied him on trips around Europe.

People in the highest government circles spoke about such relationships as well. Finance Minister Sergei Yulyevich Witte phrased things cautiously, but the meaning is clear:

“…he was constantly surrounded by several comparatively young men who were especially tenderly devoted to him. I do not mean to say that he had any sort of bad instincts, but a certain psychological abnormality — which often expresses itself in a particular kind of infatuated attitude toward young men — he undoubtedly had.”

— Finance Minister Sergei Yulyevich Witte

Hints also appeared in satirical poetry. In the poem “The Pride of Nations” by the poet V. P. Myatlev, members of the imperial family and their circle were mocked. The author called them the “Moscow Serg-ants” — a pun. On one level it sounds like “sergeants,” and on another it sounds like “Serg” (a nickname-like form of “Sergei”). This was a jab at Sergei Alexandrovich, who at the time was Moscow’s Governor-General.

The lines about “pretty little rascals with Eastern manners” were aimed at the aide-de-camp Balyasny. Here the word rendered as “little rascal” comes from an old-fashioned, colloquial, diminutive form of a term that meant “scoundrel.” In this passage it does not mean “criminal” literally; it is a mocking nickname — something like “rascal,” “rogue,” or “slick trickster.”

“The Moscow ‘Serg-ants’

With their daring aides-de-camp,

With pretty little rascals,

With Eastern mannerisms,”

— V. P. Myatlev, from the poem “The Pride of Nations”

In aristocratic and educated society, same-sex relationships existed, and many people knew about them. But for the sake of outward respectability, they often pretended that “nothing was happening.” That is why many men married — not necessarily for love, but to meet expectations. The historian Dan Healey, who studied sexuality in the Russian Empire, wrote that Sergei Alexandrovich effectively stood at the head of an informal circle of influential homosexual men in the Russian Empire — a kind of “top tier” of that milieu.

More direct rumors circulated as well — for example, about Sergei Alexandrovich’s closeness with his aide-de-camp Martynov:

“Dorofeeva Sh., a resident of Tsarskoye Selo, […] said that it is known there that Sergei Alexandrovich lives with his aide-de-camp Martynov, and that he repeatedly suggested to his wife that she choose herself a husband from among the people around her. She saw a foreign newspaper where it was printed that le grand duc Serge had arrived in Paris avec sa maîtresse / M. / “un tel” (the Grand Duke Serge with his mistress — Mr. So-and-so). Just imagine what scandals!”

— Alexandra Viktorovna Bogdanovich, diary entry

Historian A. N. Bokhanov wrote that such gossip was spread especially zealously by Grand Duchess Olga Fyodorovna. In her circle she was considered the empire’s chief gossip. She readily launched malicious rumors about those she disliked. In one quarrel she called Sergei Alexandrovich a “sodomite” — an older insult meaning a man accused of male same-sex sex. They disliked each other intensely: Sergei did not hide that he could not stand either her or her sons.

When, in 1891, Sergei was appointed Moscow Governor-General, Foreign Minister Vladimir Lamsdorf (also homosexual) recorded a joke: “Moscow used to stand on seven hills, and now it must stand on one bump.” This, too, is wordplay: a “bump” is a small hill or rise, but the sound of the word echoes the French bougre, which at the time could mean “sodomite.” The anecdote hinted at the new Governor-General’s well-known reputation.

That same year, 1891, Sergei’s younger brother, Grand Duke Pavel Alexandrovich, suffered a tragedy: his wife died in childbirth. Later Pavel entered a morganatic marriage — that is, he married a woman of “unequal birth,” and in the imperial family such a match was considered unacceptable. Pavel was forced to leave Russia.

Sergei Alexandrovich and Elizaveta Fyodorovna took responsibility for his children — Maria and Dmitrii (who was homosexual and would later become the lover of Felix Yusupov). Sergei and Elizaveta essentially became the children’s parents. In the Governor-General’s residence (today the Moscow City Hall building on Tverskaya Street) they were given separate rooms. Sergei Alexandrovich himself lived on the first floor, and Elizaveta Fyodorovna on the third.

A deputy of the First State Duma, the Kadet Vladimir Pavlovich Obninsky, wrote about Sergei Alexandrovich sharply and with hostility. The Kadets were members of the Constitutional Democratic Party, a liberal opposition party in the early 20th century. Obninsky linked Sergei’s private life to Elizaveta’s misery:

“This dry, unpleasant man, who even then influenced his young nephew [meaning Dmitrii Pavlovich], bore on his face harsh signs of the vice that was consuming him — the vice that made the family life of his wife, Elizaveta Fyodorovna, unbearable and led her, through a series of infatuations natural to her position, to monasticism.”

— Vladimir Pavlovich Obninsky on Sergei Alexandrovich Romanov

Obninsky then broadened the point and described it as a general “vice” of high society and the army:

“Many well-known people in Petersburg gave themselves over to this shameful vice — actors, writers, musicians, Grand Dukes. Their names were on everyone’s lips; many flaunted their way of life. <…> It was also curious that not all Guard regiments suffered from this vice. At that time, for example, while the Preobrazhensky men indulged in it, together with their commander, almost to a man, the Life Hussars stood out for the naturalness of their affections.”

— Vladimir Pavlovich Obninsky

Obninsky was hinting that the commander of the Preobrazhensky Regiment — Grand Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich (K. R.), Sergei Alexandrovich’s cousin — also belonged to this milieu. Sergei and Konstantin were indeed very close and remained friends throughout their lives. In Konstantin’s diaries there are mentions of his same-sex relationships.

Governor-General of Moscow

“He could often be self-confident. In those moments he would tense up, his gaze would become hard … and so people formed the wrong impression. While they took him for a cold, proud man, he helped very many people, but did so in strict secrecy.”

— Ernst Ludwig, Elizaveta Fyodorovna’s brother, about Sergei Alexandrovich

At that time, the position of Governor-General of Moscow meant authority not only over Moscow itself, but also over a number of neighboring territories. In that role, Sergei Alexandrovich did a great deal for public education, helped the poor, and supported science and the development of culture in Moscow.

He donated money to more than ninety organizations and societies. Among them were the Society for the Care, Upbringing, and Education of Blind Children; the Society for Public Health; the Moscow Architectural Society; the Society of Lovers of Natural Science; and the Russian Musical Society. In addition, Sergei Alexandrovich himself founded a Society for the Care of Children of Poor Parents. Thanks to his donations, free shelters and day nurseries opened in the Moscow Province.

He also paid attention to culture. Sergei Alexandrovich transferred archaeological finds and works of art to the Imperial Historical Museum on Red Square (today the State Historical Museum). Under him, the museum became a notable cultural center: exhibitions, lectures, and concerts began to be held there. He also took part in creating the Museum of Fine Arts on Volkhonka Street — the future Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts.

Under him, Moscow changed noticeably in terms of technology and municipal services. The first electric streetlights appeared. He banned factories from dumping waste into the Moscow River in order to improve the city’s sanitary conditions. At his initiative, the first student dormitories for Moscow University were opened. The first electric tram began running in the streets. Also under him, construction was completed on a new stage of the Mytishchi Water Supply System — the infrastructure that delivered clean water to Moscow.

But his public service also included a tragic episode. In 1896, during the coronation of Nicholas II, a terrible crowd crush occurred on Khodynka Field: people came for festive handouts and festivities, the crowd became uncontrollable, panic began, and many people died. Formally, the event was organized by the Ministry of the Imperial Court, but in public opinion part of the blame fell on Sergei Alexandrovich as well — as the head of Moscow’s administration, who was associated with maintaining order in the city.

Politically, Sergei Alexandrovich was a conservative. He supported the so-called “Zubatov” trade unions — named after Sergei Zubatov, a police official who promoted the idea of “controlled” workers’ unions. The plan was to allow workers to organize, but under state supervision, in order to sideline revolutionary organizations. Sergei Alexandrovich also opposed liberal reforms, did not support the idea of a constitution or elected bodies of government. Under him, in 1892, an order was issued that restricted the right of Jews of the lower ranks to live in Moscow and its surrounding areas.

As discontent in the country grew and revolutionary sentiment intensified, Sergei Alexandrovich resigned on January 1, 1905, leaving the post of Governor-General. But the Socialist-Revolutionary Party (the SRs) had already sentenced him to death.

Assassination

The SRs were a revolutionary party of the early 20th century that accepted the use of terror against officials and representatives of state power.

Revolutionaries considered Sergei Alexandrovich one of the main figures of the “reactionary party” — their label for people who, in their view, defended autocracy and suppressed change. They called him “the most merciless and consistent spokesman for the interests of the Romanov dynasty.”

After resigning, Sergei Alexandrovich continued to live in Moscow. He understood that he was under threat, and he began traveling around the city without his family so as not to put relatives at risk. According to the recollections of his aide-de-camp Dzhunkovsky, the Grand Duke’s security was organized very poorly.

Sergei Alexandrovich received many threatening letters and understood that he could be killed. Therefore, he often went out alone — without aides-de-camp — not wanting to endanger their lives.

Meanwhile, the SR Combat Organization (the party’s terrorist wing) studied his routine, routes, and the weak points of his security.

On February 4, 1905, at about three o’clock in the afternoon, an explosion thundered inside the Kremlin walls. Sergei Alexandrovich, as usual, departed from the Nikolayevsky Palace in the Kremlin. When his carriage passed near the Nikolskaya Tower, SR member Ivan Kalyayev threw a bomb into it. The blast was so powerful that it tore the Grand Duke’s body apart. The coachman received fatal wounds, and windows were blown out in nearby buildings.

At that moment Elizaveta Fyodorovna was in the Nikolayevsky Palace. When she learned of the tragedy, she was among the first to arrive at the scene. Without screaming or hysteria, silently, she gathered her husband’s remains with her own hands.

“Despite it being a weekday, crowds of thousands are making their way to the Kremlin to pay their last respects and bow before the ashes of the Grand Duke, who died a martyr’s death.”

— Government Herald. February 11, 1905, No. 33

Sergei Alexandrovich’s funeral took place on July 4, 1906, in the Chudov Monastery — which at that time stood on the territory of the Kremlin. At the site of his death, a memorial cross was installed to a design by the artist Viktor Vasnetsov. The cross bore an engraved Gospel phrase: “Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they do” — Christ’s words about forgiving those who do evil.

Memory and Erasure

After her husband’s death, Elizaveta Fyodorovna renounced high society and dedicated herself to helping people. In Moscow, on Bolshaya Ordynka Street, she founded the Marfo-Mariinsky Convent — a community of Sisters of Mercy who cared for the sick and supported the poor.

During the Civil War, in 1918, the Bolsheviks arrested Elizaveta Fyodorovna. Later she was killed in Alapayevsk.

After the October Revolution of 1917, the new regime destroyed things that reminded people of the imperial family. In 1918, the memorial cross at the site of Sergei Alexandrovich’s death was demolished. According to contemporaries’ recollections, Vladimir Lenin personally took part in its destruction. In 1932, the Chudov Monastery — where the Grand Duke’s grave was — was also demolished, and the tomb itself disappeared.

Decades later, during archaeological excavations in the Kremlin, Sergei Alexandrovich’s remains were found. In 1995, they were transferred to the Novospassky Monastery in Moscow — a place regarded as a burial site of the Romanov family. A memorial cross was installed there again, made in the likeness of the one that had been destroyed. A copy was also placed in the Kremlin.

The topic of Sergei Alexandrovich’s sexuality still provokes debate today: some consider the evidence sufficient, while others see it as slander and political mudslinging. At the same time, among monarchists there is a movement advocating for his canonization (recognition as a saint in Church tradition). For internal veneration, he is even depicted on icons.

🇷🇺 This piece is part of the article series “LGBT History of Russia”:

- Homosexuality in Ancient and Medieval Russia

- A Cross-Dressing Epic Hero: the Russian Folk Epic of Mikhaylo Potyk, Where He Disguises Himself as a Woman

- The Homosexuality of Russian Tsars: Vasily III and Ivan IV “the Terrible

- Uncensored Russian Folklore: Highlights from Afanasyev’s “Russian Secret Tales

- Homosexuality in the 18th-Century Russian Empire — Europe-Imported Homophobic Laws and How They Were Enforced

- Peter the Great’s Sexuality: Wives, Mistresses, Men, and His Connection to Menshikov

- Russian Empress Anna Leopoldovna and the Maid of Honour Juliana: Possibly the First Documented Lesbian Relationship in Russian History

- Grigory Teplov and the Sodomy Case in 18th-Century Russia

- Russian Poet Ivan Dmitriev, Boy Favourites, and Same-Sex Desire His the Fables ‘The Two Doves’ and ‘The Two Friends’

- The Diary of the Moscow Bisexual Merchant Pyotr Medvedev in the 1860s

- Maslenitsa Effigy: The “Man in Women’s Clothes” of Russia’s Pre-Lent Carnival

- Sergei Romanov: A Homosexual Member of the Imperial Family

- Andrey Avinoff: A Russian Émigré Artist, Gay Man, and Scientist

📣 Subscribe to our Telegram channel (in Russian): Urania. With Telegram Premium, you can translate posts in-app. Without it, many posts link to our website, where you can switch languages — most new articles are published in multiple languages from the start.

References and Sources

- Богданович А. В. Три последних самодержца. [Bogdanovich A. V. – The Last Three Autocrats]

- Боханов А. Н. Николай II. 1997. [Bokhanov A. N. – Nicholas II]

- Великий князь Сергей Александрович Романов: биографические материалы. Кн. 1: 1857–1877. 2006. [Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich Romanov: Biographical Materials. Vol. 1: 1857–1877]

- Вяткин В. В. Великий князь Сергей Александрович: к вопросу о его нравственном становлении. 2011. [Vyatkin V. V. – Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich: On the Question of His Moral Formation]

- Кон И. С. Лунный свет на заре: лики и маски однополой любви. [Kon I. S. – Moonlight at Dawn: Faces and Masks of Same-Sex Love]

- Секачев В. Великий князь Сергей Александрович: тиран или мученик? [Sekachev V. – Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich: Tyrant or Martyr?]

- Tags:

- Russia

- Queerography