Russian Empress Anna Leopoldovna and the Maid of Honour Juliana: Possibly the First Documented Lesbian Relationship in Russian History

"... she spends most of her time in the apartments of her favourite, Mengden."

- Editorial team

Empress Anna Leopoldovna ruled Russia for only a year and remains a relatively little-known figure. She is rarely discussed in school textbooks. Yet her relationship with her lady-in-waiting (often rendered as ‘maid of honour’ in English), Juliana (Julia) von Mengden, deserves attention: it may represent one of the earliest documented indications of lesbian love in Russian history.

Anna Leopoldovna and Juliana were clearly bound by an unusually close attachment. The central question, however, remains unresolved: should this be understood as a romantic relationship, or can the available accounts be explained as an intense friendship? After reviewing the facts and sources presented in this article, draw your own conclusion.

Early Years

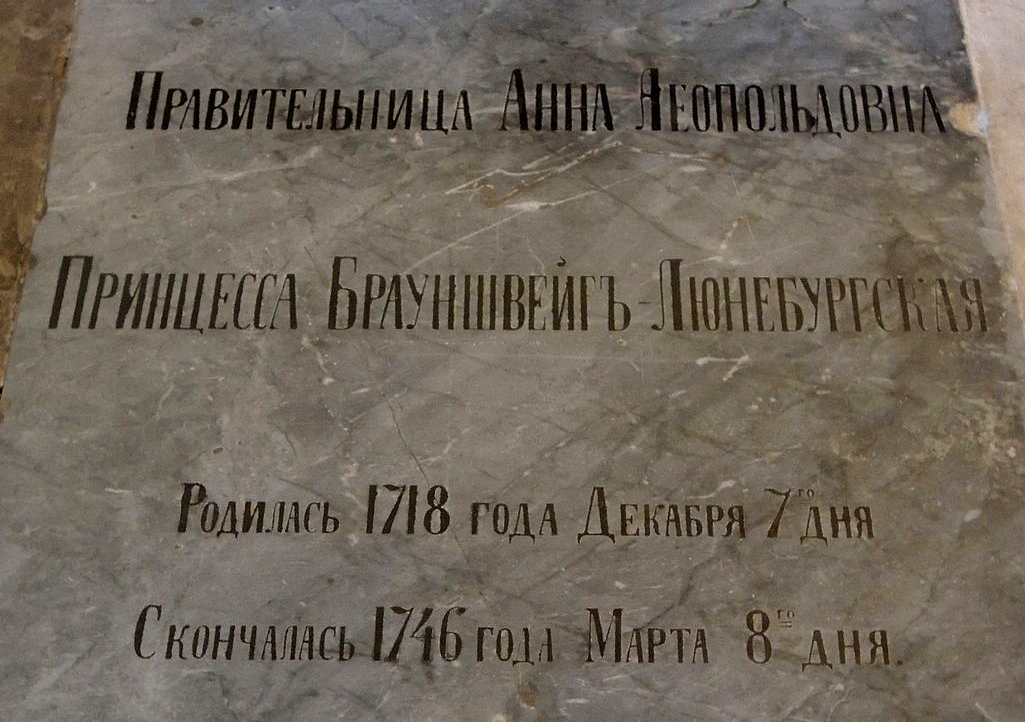

Elisabeth Catherine Christine was born on 18 December 1718 in the German duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin in northern Germany. She was the daughter of Duke Leopold of Mecklenburg and Catherine Ivanovna, a niece of Peter the Great. The marriage was, in many respects, an example of “marriage diplomacy” (a dynastic union arranged for political purposes rather than personal choice). The princess spent her early childhood in an unfamiliar setting: in Germany her mother was viewed as a “wild Muscovite duchess” and was met with hostility.

Unable to tolerate her husband’s harsh treatment, Catherine Ivanovna returned to Russia with her daughter in 1722. The marriage was not formally dissolved, but she never returned to her husband.

In 1733, after converting to Orthodoxy, Elisabeth Catherine Christine received a new name — Anna Leopoldovna. Although this occurred eleven years after her arrival in Russia, for the sake of convenience we will refer to her as Anna from the beginning.

Youth in Russia

Described as “a very cheerful little child of about four,” Anna was raised and educated in the Izmailovo Palace in Moscow. Far from court intrigues, she lived a comparatively simple life and believed she had no claim to the Russian throne. Her upbringing was informal and relaxed, with little emphasis on ceremony; she attended balls that sometimes lasted as long as ten hours.

This changed in 1730, when the throne was taken by Anna Ioannovna — Anna Leopoldovna’s aunt and namesake. The childless empress immediately singled out her niece and placed her under special protection. Anna received a house on the Neva, an order of chivalry, and a generous allowance. Tutors were hired for her in German, French, and Russian.

At the same time, according to contemporaries, Anna’s mother “gave herself over to strong drink,” becoming increasingly distant from her daughter. In June 1733, Anna’s mother died “of an illness.” Anna was left with almost no close relatives or loyal friends, aside from her aunt, the empress. From then on, she became increasingly drawn into court life — the intrigues and rivalries of the great nobles, for whom she was becoming a tool in the struggle for influence.

“The Tsarina loves her as if she were her own daughter, and no one doubts that she is destined to inherit the throne.”

— Jacobo Francisco Fitz-James Stuart, Duke of Liria and Jérica, the Spanish envoy at the Russian court

The Search for a Husband and First Infatuations

By the time Anna was fourteen, plans were being made for a dynastic marriage. The choice fell on the eighteen-year-old Prince Anton Ulrich of Brunswick, the son of a German duke. The young man — thin and short — arrived in St Petersburg to court her, but it soon became clear that he was far more interested in military affairs than in Anna.

Anna found an escape in reading. She was especially drawn to French novels, which allowed her, for a time, to step away from the cloying routines of court life and her fiancé’s indifference.

Another object of fascination was the Saxon diplomat Count Moritz Lynar — forty years old and, according to contemporaries, very handsome. Their relationship appears to have remained platonic; nevertheless, rumours of an affair reached the court, and Lynar was soon sent back to Dresden.

“Princess Anna, who is regarded as the presumed heiress, is now at an age when expectations may be formed — especially given the excellent education she has received. But she has neither beauty nor grace, and her mind has not yet shown any brilliant qualities. She is very serious, speaks little, and never laughs; this seems to me quite unnatural in so young a girl, and I think that behind her seriousness there is more stupidity than good sense.”

— Lady Rondeau, wife of the English minister at the Russian court

The Beginning of a Friendship With Juliana von Mengden

Around the same time, the seventeen-year-old Baroness Juliana von Mengden was summoned from Livonia and appointed as Anna’s lady-in-waiting. She quickly became Anna’s close friend and trusted confidante.

Juliana von Mengden, born in 1719, was a year younger than Anna. According to contemporary accounts, their relationship may have extended beyond ordinary friendship. They spent long hours alone together — relaxed at home, casually dressed, with their hair loose — which fueled court gossip about their “non-traditional” closeness.

“The princess was not a dazzling beauty, but she was a pretty blonde — kind-natured and gentle, and at the same time drowsy and lazy; she disliked any kind of work and idled away the hours with her favourite lady-in-waiting, Juliana von Mengden, for whom she felt a rare kind of friendship.”

— the Russian historian Nikolai Ivanovich Kostomarov

An Unwanted Marriage and the Birth of an Heir

Over time, Anton Ulrich gained military experience and gradually won the favour of Empress Anna Ioannovna and the court. For Anna Leopoldovna, however, his successes and ambitions meant little. “I don’t like the prince. They’re keeping me only to give birth,” she said bluntly.

Even so, the wedding was staged on a grand scale: a ceremonial procession, ornate carriages, three fountains of wine, artillery salutes from the Peter and Paul Fortress, a lavish ball, and fireworks. The main purpose of the match, however, was to produce an heir to the throne.

“All these receptions were arranged in order to unite two people who, it seems to me, hate one another with all their hearts.”

— Lady Rondeau, the wife of the English minister at the Russian court

On August 12, 1740, Anna gave birth to a son named Ivan — after his great-grandfather, the brother of Peter the Great. Russia now had an heir.

The Rise to Power

Half a year later, Empress Anna Ioannovna fell ill and, sensing the end was near, issued a manifesto declaring the infant Ivan the heir to the Russian throne. The regent, however, was not the child’s mother, but the empress’s favourite — the German Ernst Biron.

Biron held power for only a month. With the support of Field Marshal Münnich and with Juliana von Mengden’s assistance, Anna Leopoldovna organized a conspiracy that ended with Biron’s arrest and his exile to Siberia.

Anton, Ivan’s father, showed little interest in affairs of state. As a result, Anna Leopoldovna — then only 22 — assumed the duties of regent and became the de facto ruler of Russia.

The Unfulfilled “Anna the Second” and Her Relationship With Juliana von Mengden

In gratitude for Juliana von Mengden’s support during the coup, Anna Leopoldovna rewarded her generously. Juliana received the finest dresses, an estate in Livonia, and substantial cash loans.

“These young women [ladies-in-waiting], having seen little of the world, did not possess the wit needed for palace intrigue, and so the three of them did not involve themselves in it. But Juliana, the ruler’s favourite, wanted to take part in affairs — or rather, being lazy by nature, she managed to pass this vice on to her sovereign.”

— the memoirist Christoph Manstein

By the beginning of Anna Leopoldovna’s rule, the population of St. Petersburg had reached 70,000, and the city was rapidly expanding. Vegetable gardens still stood in front of the Admiralty, Nevsky Prospect remained partly undeveloped, and townspeople could still bathe naked in the Fontanka River.

“There was no creature less suited to stand at the head of government than the kind Anna Leopoldovna… Without dressing, without doing her hair, with a headscarf tied around her head, she ought to sit only in her inner rooms with her inseparable favourite, the lady-in-waiting Mengden.”

— the Russian historian Sergei Mikhailovich Solovyov

Anna Leopoldovna does not appear to have sought power and, before her appointment as regent, took almost no part in state affairs. Both contemporaries and later scholars assessed her rule cautiously and often critically: European monarchs viewed her as a weak ruler, and Russian historians later argued that she was ill-suited to the role of head of state.

At the same time, once she began her regency, Anna Leopoldovna took several steps to bring order to the state’s finances. She moved quickly to commission reports on the treasury’s income, expenditures, and debts, attempting to understand the practical details of administration.

Over time, however, this initial momentum weakened: initiatives launched with visible energy slowed as they passed through bureaucratic procedures and gradually dissolved into the everyday routine of governance.

Private Life and Withdrawal From Affairs of State

Despite the widespread criticism of her as a ruler, Anna Leopoldovna displayed a degree of mercy that was rare for her time. One telling example was her decision to review the cases of people exiled during the reign of Anna Ioannovna and Biron, and to restore the rights of many of them. Such humane treatment of “state criminals” (a period term for political offenders) appeared strikingly new.

Anna also issued decrees that reflected an intention to ease the everyday burdens of her subjects. In particular, she repealed Peter the Great’s ban on building stone buildings outside St Petersburg, and relaxed restrictions for those who wished to take monastic vows.

“Her actions were open and sincere, and nothing was more unbearable to her than the pretense and constraint so necessary at court. That is why people who had grown accustomed, in the previous reign, to the coarsest flattery unjustly considered her arrogant and supposedly contemptuous of everyone. Beneath an outward coldness, she was inwardly lenient and frank… […] she always dressed with displeasure whenever, during her regency, she was required to receive visitors and appear in public…”

— Münnich

According to the English envoy Finch, Anna’s feelings for Juliana resembled “a man’s most ardent love for a woman.”

“I cannot deny that she possesses considerable natural ability, a certain perceptiveness, extraordinary good nature and humanity; but she is undoubtedly too restrained by temperament: large gatherings weary her, and she spends most of her time in the apartments of her favourite, Mengden, surrounded by the relatives of this lady-in-waiting.”

— the English ambassador Finch

Over time, Anna Leopoldovna increasingly withdrew from affairs of state. Formally, she continued to perform her duties, but her interest in governing the country gradually waned.

She was drawn more and more to seclusion and to the company of a small circle of intimates. The lady-in-waiting Juliana von Mengden still occupied an important place in her life: in Juliana’s rooms, Anna often held evening gatherings with friends.

“The ruler still feels disgust for her husband; it often happens that Juliana Mengden refuses him entry to this princess’s room; sometimes he is even made to leave the bed.”

— the French diplomat, the Marquis de la Chétardie

Count Moritz Lynar, whom she had recalled from Saxony, again came close to Anna, along with other trusted figures. She spent evenings with this circle playing cards and talking. It is likely that Anna felt attachment to both men and women.

“The grand duchess thought far more about finding a place for her favourite than about the other affairs of the empire.”

— the memoirist Christoph Manstein

With Lynar, Anna no longer attempted to conceal her feelings and displayed her affection openly.

“She often held meetings in the third palace garden with her favourite, Count Lynar. She always went there accompanied by the maid of honor Juliana… and when the Prince of Brunswick [Anton, Anna’s husband] wished to enter the same garden, he found the gates locked, and the guards had orders to let no one in… Since Lynar lived near the garden gate in Rumyantsev’s house, the princess ordered a summer house to be built nearby — what is now the Summer Palace. In summer she ordered her bed to be placed on the balcony of the Winter Palace; and although screens were set up to conceal it, from the second floors of the houses neighboring the palace one could still see everything.”

— Münnich

One day the chamberlain Fyodor Apraksin reproached Anna Leopoldovna for “dining alone with the lady-in-waiting von Mengden, when it would have been more proper to dine with her husband — and, he said, that lady-in-waiting stood in great favor with Her Imperial Highness.” In response, Anna cursed him, calling him “a Russian scoundrel”.

Unlike Empress Anna Ioannovna, who preferred lavish entertainments, Anna Leopoldovna showed no interest in hunting, horseback riding, or shooting. She favored quieter pursuits — in particular, she eagerly kept and bred birds. In her rooms she had a parrot, an Egyptian dove, a trained starling, and two nightingales.

In July 1741, Anna gave birth to a daughter, Catherine. The nursery was constantly attended by a nanny, a wet nurse, and her favourite lady-in-waiting, Juliana von Mengden.

Coup and Downfall

The period of relative calm ended on July 28, 1741, when Sweden declared war on Russia in an attempt to recover territories lost under Peter the Great. Fighting began in Finland.

That same month, with Anna Leopoldovna’s consent, her favourite, Juliana von Mengden, became engaged to Count Moritz Lynar. Anna awarded Lynar Russia’s highest order — the Order of St. Andrew the Apostle the First-Called — and he then left for Saxony on official business.

For a time, St Petersburg was left almost without troops capable of protecting Anna and her supporters.

In the autumn of 1741, a conspiracy took shape against Anna Leopoldovna and her circle. Its leader was Elizabeth Petrovna, the daughter of Peter the Great. As early as December 1740, she suspected that Anna did not intend to confine herself to the role of regent and meant to become empress in her own right. Elizabeth openly scorned Prince Anton, calling him a “simpleton” even in the presence of soldiers from his regiment.

On November 24, a palace coup took place and ended in a complete, bloodless victory for the conspirators. The army and the civil authorities did not have time to respond: while Anna’s courtiers were enjoying themselves at a ball, Elizabeth was already in the guards’ barracks among her supporters.

She was backed by non-commissioned officers who swore allegiance to the new empress, and a detachment of grenadiers soon moved toward the palace. They entered the apartments without resistance and arrested everyone, including the young Emperor Ivan.

“Having finished at the guardhouse, Elizabeth went to the palace, where she met no resistance from the sentries except for one non-commissioned officer, whom she immediately had arrested. Entering the ruler’s room, where she was sleeping together with the lady-in-waiting Mengden, Elizabeth said to her: ‘Sister, it’s time to get up!’ The ruler, waking, said: ‘What, is that you, madam!’ Seeing grenadiers behind Elizabeth, Anna Leopoldovna understood what was happening and began to beg the tsarevna (the emperor’s daughter) not to harm either her children or the young lady Mengden, from whom she did not wish to be separated.”

— the Russian historian Sergei Mikhailovich Solovyov

Exile and Interrogations

Once arrests were made, formal legal proceedings began. Field Marshal Münnich was sentenced to be quartered, and Juliana von Mengden was sentenced to death. At the last moment, however, Elizabeth commuted both sentences and sent them into exile in Siberia.

The court found Anna Leopoldovna and her husband guilty of violating their oath and of usurping power — which, in the prosecution’s view, rightfully belonged to the daughter of Peter the Great. As a result, Anna and her family were long remembered in the public imagination as “usurpers,” and their punishment was exile — initially, to their German homeland.

Before her departure, Anna Leopoldovna was permitted to submit one final petition to the new empress. She asked for only one thing: permission to remain close to Juliana von Mengden. Elizabeth granted the request.

The exiles’ journey began in Riga, then part of the Russian Empire. Yet instead of being sent to Germany, the family spent nearly a year under arrest in Riga Castle, living in uncertainty about what would happen next.

Correspondence began between Riga and St Petersburg. Elizabeth Petrovna opened an investigation into the disappearance of royal jewels, suspecting Anna Leopoldovna and her circle. Juliana von Mengden was also accused of attempting to influence the succession to the throne. Nevertheless, the investigators’ main focus remained the fate of the missing valuables.

Juliana gave a detailed account of the jewelry and precious items. A set (i.e., a matching suite of jewelry), snuffboxes, and other objects, she said, had been distributed to various people on Anna Leopoldovna’s orders; only a few especially valuable pieces had been given to her personally as gifts. When questioned about money, Juliana von Mengden stated that she had received large sums from Anna, much of which she passed on to her fiancé, Lynar, and to others, and that she also directed funds to donations to the church.

At one of the later interrogations, Juliana von Mengden (whom Empress Elizabeth called “Zhulka” — a scornful, diminutive nickname) claimed that Anna Leopoldovna had personally broken up some pieces of jewelry. The stones from the settings were placed in the princess’s cupboard, but where the caskets from the cupboard later went remained unknown.

While the interrogations continued, Anna Leopoldovna and Anton Ulrich spent a year in the Riga citadel (in the building that now houses the residence of the President of Latvia). Their long-awaited departure never took place. At first, the spouses were kept apart, but in February 1743 they were allowed to be together, although the conditions of confinement remained strict.

Initially, Anna Leopoldovna and her husband hoped to be released and tried to occupy themselves. Anna rode on the swings in the castle courtyard, while Prince Anton Ulrich played a bowling-like game (ninepins) with the ladies.

The Final Years

Over time, the suspicious Elizabeth ordered the family to be transferred to a more “reliable” place. They were first subjected to a bleak confinement in the fortress of Ranenburg (now Chaplygin in Lipetsk Oblast). On July 27, 1744, however, Elizabeth commanded that Anna Leopoldovna’s family be sent to the Solovetsky Monastery.

Juliana von Mengden, by contrast, was ordered to remain in the fortress. Anna’s servants understood that separation from Juliana would be a severe blow to her, and they sent a request to the capital asking that the lady-in-waiting be allowed to travel with them — but they received no reply. Juliana never departed. Anna never saw her faithful “Julia” (Juliana) again: the lady-in-waiting remained in Ranenburg.

When the prisoners reached Kholmogory (now in Arkhangelsk Oblast), they could not continue because ice blocked the Northern Dvina. As a result, Elizabeth ordered the exiles to stay there, under conditions of strict secrecy.

Empress Elizabeth again recalled the missing jewels and instructed the guards to question Anna about the fate of the diamonds. To the order, Elizabeth added a personal note: “And if she begins to deny that she gave any diamonds to anyone, tell her that I will be forced to investigate Juliana; and if she cares for her, she should not let her be subjected to such torment.”

It is unknown how the guard spoke with Anna about this. Most likely, Anna rejected the accusations, because no further persecution followed, and Juliana von Mengden in Ranenburg was left alone.

Anna’s Death and Juliana’s Fate

The posthumous treatment of the disgraced family members was determined in advance. Elizabeth issued a decree stating that if any member of the family died — especially Anna Leopoldovna or Prince Ivan — the body, after an autopsy and preserved in alcohol, was to be sent to the capital immediately.

Anna Leopoldovna did not have long to live. Very little is known about the final months of her life. On March 17, 1746, it was reported that the princess had developed a fever, and the next day — that she had died. She was 28.

When news of Anna Leopoldovna’s death reached St Petersburg, preparations began to receive her body. Anna was buried in the Annunciation Church of the Alexander Nevsky Monastery, beside her mother.

After Anna Leopoldovna’s death, her family met a tragic fate. Her son, the former emperor, was kept in permanent isolation in prison and was killed by guards in 1764. Prince Anton Ulrich spent the rest of his life in Kholmogory, went blind, and died in 1774.

Juliana remained in exile in Ranenburg until the end of 1762. Then, by decree of Empress Catherine II, she was allowed to return to Livonia. Settling on her mother’s estate, Juliana rarely left it and devoted herself to managing the household.

She readily shared memories of the past and of the years of imprisonment, but spoke about Anna Leopoldovna’s court cautiously and only rarely. In her later years, Juliana suffered bouts of fever and died in October 1787.

🇷🇺 This piece is part of the article series “LGBT History of Russia”:

- Homosexuality in Ancient and Medieval Russia

- A Cross-Dressing Epic Hero: the Russian Folk Epic of Mikhaylo Potyk, Where He Disguises Himself as a Woman

- The Homosexuality of Russian Tsars: Vasily III and Ivan IV “the Terrible

- Uncensored Russian Folklore: Highlights from Afanasyev’s “Russian Secret Tales

- Homosexuality in the 18th-Century Russian Empire — Europe-Imported Homophobic Laws and How They Were Enforced

- Peter the Great’s Sexuality: Wives, Mistresses, Men, and His Connection to Menshikov

- Russian Empress Anna Leopoldovna and the Maid of Honour Juliana: Possibly the First Documented Lesbian Relationship in Russian History

- Grigory Teplov and the Sodomy Case in 18th-Century Russia

- Russian Poet Ivan Dmitriev, Boy Favourites, and Same-Sex Desire His the Fables ‘The Two Doves’ and ‘The Two Friends’

- The Diary of the Moscow Bisexual Merchant Pyotr Medvedev in the 1860s

- Maslenitsa Effigy: The “Man in Women’s Clothes” of Russia’s Pre-Lent Carnival

- Sergei Romanov: A Homosexual Member of the Imperial Family

- Andrey Avinoff: A Russian Émigré Artist, Gay Man, and Scientist

📣 Subscribe to our Telegram channel (in Russian): Urania. With Telegram Premium, you can translate posts in-app. Without it, many posts link to our website, where you can switch languages — most new articles are published in multiple languages from the start.

References and Sources

- Анисимов Е. В. Иван VI Антонович. [Evgeny V. Anisimov - Ivan VI Antonovich]

- Корф М. А. Брауншвейгское семейство. [Modest A. Korf - The Brunswick Family]

- Курукин И. В. Анна Леопольдовна. [Igor V. Kurukin - Anna Leopoldovna]

- Манштейн Х., Миних Б., Миних Э. Перевороты и войны. [H. Manstein, B. Münnich, E. Münnich - Coups and Wars]

- Tags:

- Russia