Peter the Great’s Sexuality: Wives, Mistresses, Men, and His Connection to Menshikov

Was Russia’s first emperor bisexual? Or did he love only women?

- Editorial team

Peter the Great entered history as a reformer who drastically changed the old order. But his private life was no less turbulent and contradictory.

A great many sources from that era have survived: letters, diaries, memoirs, and notes by foreigners at court. They show that rumors of Peter’s possible relationships with men circulated widely. Yet many historians either skirted the topic or flatly denied it.

In this article, we’ll first take a brief look at the tsar’s biography and examine his relationships with women — wives and mistresses.

🏳️🌈 In the second half, we’ll consider all rumors and documents about Peter the Great’s possible relationships with men: memoirs, diaries, letters, and archival materials.

Birth, Childhood, and the Formation of Character

Peter was born on June 9, 1672, in Moscow. His mother, Natalya Kirillovna Naryshkina, was the second wife of Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich; she was 21 at the time of Peter’s birth. He spent his childhood under the care of nannies and servants, like other royal children.

When Peter was four, his father died: the tsar suddenly fell ill and passed away. The throne went to a son from the first marriage — Fyodor. He was seriously ill: his legs were constantly swollen.

Fyodor did not rule for long and died in 1682. After his death, a struggle for power began between two clans at court: the Naryshkins (Peter’s maternal family) and the Miloslavskys (relatives of the tsar’s first wife). The question was who would be tsar: Ivan or Peter. Ivan — Peter’s older half-brother on his father’s side — was also frail and sickly.

In May 1682, a revolt broke out in Moscow. The Miloslavskys convinced the streltsy — the tsar’s musketeer corps and a powerful military-political force — that the Naryshkins had killed Ivan. They stormed into the Kremlin and saw Ivan alive. But they could no longer stop: they demanded blood and killed several boyars — high-ranking nobles — including men close to Peter. Peter remembered this horror for the rest of his life — and later he would take revenge.

In the end, both brothers were proclaimed tsars, and the governance of the country was entrusted to their elder sister Sophia — as regent, until they could rule on their own.

Peter studied little: his tutors gave him only the basics of literacy, and he wrote with mistakes all his life. Yet from an early age he was captivated by crafts. He learned carpentry, joinery, and blacksmithing — for a Russian tsar, this was almost unthinkable.

But more than anything, he was drawn to the army and the sea. In the village of Preobrazhenskoye, he staged “play” battles: officially they were treated as a game, but in reality there were real muskets and cannons, and everything looked quite serious.

At that time, ships in Russia were built irregularly. Peter found the most practical nautical knowledge among foreigners, so he spent more and more time in the German Quarter — the Moscow district where visiting Europeans lived (not only Germans; “Germans” was then often used as a blanket term for foreigners in general).

In 1694, Peter’s mother died. He broke with tradition: he did not attend the official funeral. He endured his grief alone and later secretly mourned her at her grave. Two traits — contempt for ritual and, at the same time, deep but hidden feelings — would stay with him for a long time.

Reign: In Brief

Without going into detail, let’s list the key milestones of his reign.

The “Grand Embassy” of 1697–1698 was a major trip by Peter and his entourage to Europe. It gave him first-hand exposure to European technology, the military, governance, and everyday life.

Then came the creation of the Russian Empire, military reforms, and victory in the Great Northern War (1700–1721) against Sweden, which secured Russia’s access to the Baltic Sea. After that — expansion eastward and the Caspian Campaign, after which Russia asserted itself even more strongly as a major power.

Peter rebuilt the country in almost every sphere: he created a regular army and navy, reshaped the system of government, and influenced education and culture. This required harsh decisions and left its mark on his character. The constant pressure of power and war made him cruel, suspicious, and intolerant of criticism.

Equally important was how he chose people. Peter valued ability over birth. Much of his maternal family had been destroyed during the uprising; he ignored his wife’s relatives; and his close childhood friends did not belong to the “great” aristocracy. Under him, commoners, foreigners, and people of another faith could rise to the highest offices — if he considered them useful and talented.

Peter the Great combined the reformer and the despot, the destroyer of the old and the creator of the new.

Peter the Great’s Appearance and Character

“Tsar Peter Alekseevich was very tall, rather lean than stout; his hair was thick, short, and dark chestnut in color; his eyes were large, black, with long eyelashes; his mouth was well-shaped, though the lower lip somewhat marred; his expression was splendid, inspiring respect at first glance.”

— Filippo Balatri, Italian singer (1698)

“The Tsar is very tall; his face is very handsome; he is very slender. Yet alongside all the outstanding qualities nature has given him, one would wish his tastes were less coarse… He told us that he himself works on the building of ships, showed his hands, and made us feel the calluses. […] As for his grimaces [convulsions], I had imagined them worse than I found them, and it is not in his power to control some of them. It is also clear that he was not taught to eat neatly, but I liked his naturalness and ease — he began to behave as if at home.”

— Sophia Charlotte of Hanover, Electress of Brandenburg, on meeting Peter the Great

“In the morning His Majesty rises very early, and more than once I have met him at the earliest hour on the embankment, walking to Prince Menshikov, or to the admirals, or to the Admiralty and the ropewalk. He dines around noon, wherever and with whomever it may be, though most willingly with ministers, generals, or envoys… After dinner, having rested for about an hour in the Russian manner, the Tsar takes up work again and only late at night retires to sleep. He does not care for card games, hunting, and the like, and his sole amusement — by which he sharply differs from all other monarchs — is travel by water.”

— anonymous author of the pamphlet “A Description of St. Petersburg and Kronstadt in 1710 and 1711”

First Marriage: Eudoxia Lopukhina

By seventeen, Peter was expected to marry — this was decided by his mother, Natalya Kirillovna. In the tradition of the time, marriage meant that a young man had become an adult and could act more independently. For Peter, it was also a way to weaken the power of Sophia, who as regent effectively held the government in her hands.

The bride was Eudoxia Lopukhina — noble and beautiful, but very “old-Moscow” in her upbringing and tastes. Peter quickly found her alien in spirit. At first there may have been affection between them, but about a month after the wedding he fled back to his ships and his pursuits. His wife’s obedience and her attachment to the old order filled him with boredom and irritation.

In 1690, their son Alexei was born, but it did not make the family stronger. After returning from the Grand Embassy, inspired by Europe, Peter forced Eudoxia into a convent — in effect, he severed their union.

Relationship With His Mistress Anna Mons

In the German Quarter, Peter the Great met Anna Mons — the daughter of a wine merchant. For a long time, Anna became Peter’s chief passion. She was cheerful, quick-witted, and loved dancing and conversation — sharply different from his wife Eudoxia, who had been raised in old Muscovite traditions.

The Tsar visited the Mons household more and more often. Eudoxia tried to bring her husband back — she wrote touching letters.

“Greetings, my light, for many years. We beg your mercy, sovereign — please come to us without delay. And by my mother’s grace I am alive. Your little wife, Dunka (Eudoxia), bows to the ground.”

— Eudoxia Lopukhina in a letter to Peter the Great

But all her letters went unanswered. Peter no longer held on to the family.

Anna Mons remained the Tsar’s mistress for more than ten years. But it seems that, for her, the relationship was not as much the “meaning of life” as it was for Peter. At some point Anna acquired a new admirer — the Prussian envoy Georg Johann von Keyserlingk. When Peter learned of it, he flew into a rage, and Anna was placed under house arrest.

Peter met with Keyserlingk. According to the envoy himself, the Tsar declared that he had “raised the maiden Mons for himself, with the sincere intention of marrying her, but since she has been seduced and corrupted by him, he wants neither to hear nor to know anything of her or her relatives.”

Menshikov, Peter’s closest associate, added that Mons was “a vile, public woman, with whom he himself had debauched just as much as Keyserlingk.” After that, Menshikov’s servants beat the diplomat and threw him down the stairs.

Despite the scandal, Keyserlingk got what he wanted: in 1711 he married Anna. But half a year later he died. Anna tried to rebuild her life, but soon she herself died of consumption — the period term for tuberculosis.

There is no evidence of any pregnancy of Anna Mons by Peter.

Second Marriage: Catherine I

In 1711, in the midst of the war with Sweden, Peter the Great announced that he had a new wife — Catherine.

Before Peter, monarchs’ extramarital affairs in Russia were tolerated. But an official marriage between the tsar and a woman “from the wrong circle” was considered almost unthinkable. The tsar was seen not only as a ruler, but as a sacred figure, surrounded by special ideas about “rightness” and order. A union with a former captive looked scandalous, but Peter was not in the habit of submitting to tradition.

Before her baptism, Catherine was named Marta. She was born in Livonia — a Baltic region that today mostly lies within Latvia and Estonia. Her mother was the mistress of a nobleman, but soon Marta was orphaned and ended up in the household of a pastor (a Lutheran priest).

In 1702, she was captured by the Russians during the siege of Marienburg (today the town of Alūksne in Latvia). At first, Marta belonged to a non-commissioned officer (a junior commander), then to the field marshal Sheremetev, and later to Alexander Menshikov. In 1703, Peter saw her in Menshikov’s house and took her for himself. The fact that she had previously been Menshikov’s concubine, apparently, did not trouble Peter.

After converting to Orthodoxy, Marta became Catherine. She bore Peter several children and gradually took a special place in his life: she became not merely a mistress, but someone who knew how to calm the tsar during fits of rage and helped him endure severe convulsions.

In 1711, Peter married her quietly, without fanfare — and in 1724, he crowned her officially. Thus a former “German servant-girl” became the first woman to stand at the head of the Russian Empire — the future Empress Catherine I.

Unlike Anna Mons, Catherine was physically resilient and accompanied Peter almost constantly: on campaigns, at ship launchings, and at military reviews. Contemporaries recalled that she could easily hold the tsar’s heavy scepter — a symbol of power so massive that servants struggled to manage it.

One hundred and seventy of Peter’s letters to Catherine have survived. He wrote to her warmly: the letters could begin with an address like “Katerinushka, my friend.”

“For God’s sake, come as soon as possible; and if, for some reason, it is impossible to come soon, then write back — for it is not without sorrow for me that I neither hear nor see you.”

— Peter the Great, in a letter to Catherine

Anna Mons’s downfall did not ruin her brother. Willem Mons — also handsome and charming — built a career at court and became Catherine I’s most trusted man. He exploited his closeness to the empress and, for bribes, helped others gain access to her. This affected Peter’s decisions as well: if someone controls the “doorway” to the ruler, he inevitably begins to control petitions, rumors, and the mood.

Everything might have continued, if not for one dangerous detail: Willem was involved in a secret affair with Catherine.

The unraveling began with a denunciation. In November 1724, Peter — already aware of Mons’s schemes — arranged a family supper. At the table sat Catherine and Willem himself. At some point, the tsar asked what time it was. Catherine glanced at the clock — a gift from Peter — and answered:

— Nine.

Peter silently took it, moved the hands, and said coldly:

— You’re mistaken. Midnight. Everyone should go to bed.

The guests dispersed. Minutes later, Mons was arrested. Under interrogation he confessed to everything — even without torture. But formally the charges mentioned only bribery: Catherine’s name was not spoken. The sentence was one — death.

On the day of the execution, Catherine kept herself composed, but the French ambassador Campredon reported to Paris:

“Although Her Majesty hides her grief as much as possible, it is written on her face.”

— the French ambassador Campredon

After that, Peter acted with demonstrative cruelty: he ordered the severed head to be preserved in alcohol and displayed in Catherine’s chambers. After this, their relationship noticeably cooled. Peter spent time with his mistress Maria Cantemir, a representative of a noble Moldavian family, and spoke to his wife scarcely at all.

Only in January 1725 — a month before Peter’s death — did the spouses reconcile.

Later a legend appeared: that as he lay dying, Peter tried to write the name of his heir, but his hand weakened, and he managed only: “Give everything…” — and did not finish. After that, politics became decisive. Menshikov played a major role: at the critical moment he backed Catherine — and it was thanks to this that she took the throne.

Other Mistresses

Peter the Great became famous for countless affairs. His leib-medic — the personal court physician — Dr. Areskin once remarked with irony that the tsar seemed to be inhabited by an entire “legion of demons of lust,” meaning an uncontrollable pull toward amorous adventures.

During the Grand Embassy, Peter generally avoided entertainment. But in London he made an exception: he had a brief liaison there with the actress Letitia Cross. The affair ended quickly, and before leaving Peter gave her a “gift” — 500 pounds sterling. Cross said she had expected a larger sum, but Peter only smirked: in his view, he had already paid far too generously.

“… the sovereign sometimes liked to chat with a beauty — but for no more than half an hour. It is true: His Majesty loved the female sex; however, he did not become passionately attached to any woman and quickly extinguished the flame of love, saying: ‘A soldier ought not drown in luxury; forgetting one’s service for a woman is unforgivable. To be a mistress’s captive is worse than to be a captive in war: from an enemy one may soon be free, but a woman’s chains are long-lasting.’ He took the one he happened to meet and like — but always with her consent and without coercion.”

— Andrei Nartov

In Europe of that era, monarchs’ romances surprised no one. Royal favorites — established mistresses at court — were a normal part of “court life.” A showy example is the Polish king Augustus II the Strong: he was credited with 354 illegitimate children. For society, this looked not like shame, but like a sign of a ruler’s vigor: he was young, energetic, and “full of life,” if he could conquer women.

In Russia the attitude was broadly similar. Peter’s infatuations did not become a major scandal among the nobility — or even on the church’s side. Moreover, his circle often copied this style. For example, Prince Ivan Trubetskoy, finding himself in Swedish captivity, presented himself as a widower and took a mistress.

But Peter himself, it seems, sometimes felt embarrassed by his affairs and disliked being teased about them. In 1716, the Saxon minister Flemming described a dinner of Peter the Great with the King of Denmark. They drank more than usual, and the Danish monarch decided to needle Peter:

— Brother, I’ve heard you have a mistress as well!

Peter did not take it as a joke and answered sharply:

— Brother, my favorites do not cost me much, whereas your public women cost you thousands of thalers — which you could put to far better use.

Menshikov assembled a group of young women at court; among them was Varvara — the sister of his wife. He wanted to bring Varvara close to the tsar in order to strengthen his own position beside Peter even further. Varvara, they wrote, was not considered a beauty, but she was intelligent.

The foreigner Villebois described a scene at dinner: Peter told her bluntly, “I don’t think anyone would be captivated by you, poor Varya — you are too ugly; but I will not let you die without having tasted love.” Then, according to this source, the tsar “right there, in front of everyone, threw her onto a sofa and fulfilled his promise.”

Catherine treated her husband’s infatuations calmly. Sometimes she even chose mistresses for him herself, considering them trivial amusements that did not threaten their marriage. The only woman who truly worried her was Princess Maria Cantemir.

Maria came from an eminent family. Her father was the Moldavian–Wallachian prince Dmitry Cantemir. After his defeat by the Turks in 1711, he moved to St. Petersburg and entered Peter’s circle. In 1722 it became known that Maria was expecting Peter’s child. If a son had been born, it could have drastically changed the balance at court: Maria had princely dynastic pedigree and might have seemed to the nobility a “more suitable” tsarina than Catherine. But Maria lost the child.

Punishment for Talking About the Tsar’s Affairs with Women

Ordinary people often condemned the tsar’s womanizing. But in Peter the Great’s era, careless words about the sovereign could end horribly for common folk. In the archives of the Preobrazhensky Prikaz — an institution that handled political investigations, interrogations, and “treason cases” — materials about such conversations have survived.

In 1701, a former priest, Nikifor Plekhanovsky, informed on the peasant Danila Kuzmin. Kuzmin allegedly spread rumors that Peter had forcibly tonsured his wife as a nun, while he himself lived “in debauchery” with German women — and even took them along on trips. Even more terrifying was another accusation: Kuzmin said that in Voronezh a young woman died after being raped by the tsar. The case dragged on for a long time; interrogations were conducted under torture. In the end, Kuzmin died in the dungeons — in the investigation prison.

Around the same time, a man from Kursk named Avtomon Pushechnikov accused his relative Mikhail Bukreev of “indecent speech.” Bukreev had told a merchant a story: during a plague, Colonel Baltazar had been quartered at his home, and supposedly confessed that the tsar had seduced his wife — and, as a reward, gave him two barrels of oil and two barrels of honey, and then made him a colonel.

Under interrogation, Bukreev spoke more cautiously: yes, he had mentioned Peter’s affairs with German women, but he did not want to accuse the tsar of debauchery. He really had seen the oil and honey at Baltazar’s place, but Baltazar explained that it was a reward for service. The court sentenced Bukreev to the knout, branding, and exile to Siberia. However, he did not live to receive the punishment.

There is one more episode. A certain Dmitry Isaev admitted that he had discussed the tsar’s private life with a friend. He claimed that “even the Most Serene Prince [Menshikov] has been granted his favors for no other reason than that the Great Sovereign lives in debauchery with his wife and her sisters,” and that “he was with the regiments, and the sovereign’s Swedish dog died, and he — the sovereign — and the Most Serene Prince went with the prince’s wife to look at that dog. And at that time the Most Serene Prince’s wife went with the sovereign and the Most Serene Prince in a single shirt.” How the investigation ended is unknown.

Peter’s Homosexual Side

Peter the Great — a man with an extremely turbulent private life — may have had relationships not only with women, but also with men.

It is important to state at once: there is no direct proof. There are no confessions by Peter himself, no documents on the level of “here is a letter where he says this outright.”

But there is a great deal of indirect evidence: rumors, retellings, notes by foreigners, memoirs, diaries, and criminal cases. These materials are scattered and often relayed third-hand — especially in foreign sources, where Russian court life was frequently described from the outside, colored by conjecture and political emotion.

Peter’s relationships with women are described in detail: wives, mistresses, affairs, letters. That is why many people reason like this: since he clearly took an interest in women, then “he definitely couldn’t have been with men.” But that is 21st-century logic.

In the early 18th century, sexuality was understood differently. The familiar division into “homo-” and “hetero-” as stable identities did not exist. People could enter into different kinds of relationships. History offers many examples of men who had families and children, and yet also had same-sex relationships. It depended on personal habits, circumstances, the norms of one’s environment, and how much a person feared exposure.

How Early-18th-Century Russian Society Viewed Homosexuality

When evaluating rumors about Peter’s private life, it matters not only what the gossip said, but also the cultural backdrop: what was considered permissible, what was considered “sin,” what was merely indecent, and what was seen as a threat to the state.

The “sin of Sodom” in pre-Petrine Rus’ was not unheard of: foreign travelers wrote about it, and Orthodox priests warned their flocks. Under the first Romanovs, the phenomenon did not fundamentally disappear, and Peter’s youth fell precisely at the end of that era.

We have already written about this:

👉 Homosexuality in Ancient and Medieval Russia

So if Peter really did engage in same-sex relationships, it would hardly have caused a “social explosion.” More likely, it would have been perceived as indecency — a sin and a breach of propriety, especially for a sovereign. But it would have been something people tried not to bring into the open, rather than something that “brings society down.”

Source Context on Peter: Memoirs, Rumors, and Anecdotes

Peter’s reforms sharply split society: some saw him as a hero and the builder of a new Russia, while others saw him as a destroyer of familiar life and an enemy of the “Old Faith”. Opponents of change spread rumors, sometimes outright absurd ones. Among them were stories about the tsar’s homosexual relationships.

Alongside rumors, there were also “anecdotes.” In the eighteenth century, the word anecdote often meant not a joke in the modern sense, but a short story “about an incident.” It was something between a memoir and a literary vignette: sometimes it could contain a real episode, but it almost always passed through retelling, embellishment, and invention.

From here on, it’s important to understand which authors these stories rest on — and how far they can be trusted.

Andrei Nartov. He is often called “Peter’s lathe-turner.” A collection titled Stories and Anecdotes about Peter the Great is attributed to him. But there is also a theory that it was written not by Nartov, but by his son — 61 years after Peter’s death. Historians (for example, P. A. Krotov) consider these texts a work of literary fiction.

Jacob von Stählin. A German historian who came to Russia in 1735, after Peter’s death. In 1785 he published Authentic Anecdotes about Peter the Great in German. He spent more than 40 years collecting stories about the tsar and then reworked them.

Kazimierz Waliszewski. A Polish historian who wrote a great deal about Peter. But his works are often criticized: specialists do not consider them a reliable foundation, because he sometimes draws freewheeling conclusions and includes dubious details.

Nikita Villebois (François Guillaume de Villebois). A French adventurer in Russian service. He is credited with The Memoirs of Villebois, a Contemporary of Peter the Great. But researchers consider this text a forgery. A manuscript preserved in Paris bears the note: “Anecdotes about Russia; Villebois is not the author.”

Friedrich Bergholz. A German nobleman who lived in Russia under Peter. He kept a detailed diary and recorded events carefully and regularly. His notes are usually considered reliable — one of the “strong” sources for the period.

Boris Kurakin. A close associate of Peter’s and Russia’s first permanent ambassador abroad. He wrote A History of Tsar Peter Alekseevich. This is a source from someone within the ruling circle who knew the system from the inside. It is usually treated as more reliable testimony than later compilations of rumor.

The line between truth and invention remains unclear here. So it helps to keep a simple checklist in mind:

- Nartov — likely a later literary text by his son;

- Stählin — collected and edited rumors;

- Waliszewski — questionable as a “solid foundation”;

- Villebois — possibly a forgery;

- Bergholz — generally more trustworthy;

- Kurakin — generally more trustworthy.

Peter the Great and Sergeant Moisey Buzheninov

In his youth, Peter — already married — increasingly lived not in the palace but “elsewhere,” among simpler people. Around him were young men from the lower ranks, not boyars and not aristocrats. Among these companions, Moisey Buzheninov stood out in particular — the son of a servant attached to the Novodevichy Convent.

Prince Boris Kurakin describes that period like this:

“Many of the young lads, common folk, came into favor with His Majesty — and especially Buzheninov, and many others who were around His Majesty day and night. […] And for the said Buzheninov a house was built by the headquarters of the Preobrazhensky Regiment, and in that house His Majesty began to spend the night; and thus the first separation from the tsaritsa [his wife] Eudoxia began. Only during the day did he come to his mother at the palace, and sometimes dined at the palace, and sometimes in that courtyard of Buzheninov’s.”

— Prince Boris Kurakin on Peter the Great

From this comes a hypothesis: perhaps the first real crack in Peter’s marriage to Eudoxia began even before Anna Mons. Maybe the first separation was connected to Moisey Buzheninov — the future sergeant — in whose house the young tsar preferred to spend the night, avoiding a marriage that had become burdensome to him. In this context, the later appearance of Alexander Menshikov as Peter’s intimate friend becomes easier to understand.

Peter the Great and Pavel Yaguzhinsky

After Peter grew close to Menshikov, he gained another favorite — Pavel Yaguzhinsky. He came from Lithuania and was the son of a teacher of organists.

His appearance at the tsar’s side may have been part of court politics. It is believed that Chancellor Fyodor Golovin recommended Yaguzhinsky in order to weaken Menshikov’s influence. A chancellor was one of the top figures in foreign policy and state administration; a man of that rank could indeed “promote” the right people into the tsar’s proximity.

Yaguzhinsky’s career began at the very bottom. In Moscow he cleaned boots and took on other odd jobs. The foreign contemporary Friedrich Christian Weber wrote about these occupations in a way that “a sense of decency forbids him to elaborate on them” — implying work he considered improper or degrading to describe. Then came a sudden rise. Yaguzhinsky became one of Peter’s favorites and, within a few years, received the post of Procurator General of the Senate.

Such a meteoric ascent almost always breeds rumors. Ill-wishers whispered that Yaguzhinsky’s success was explained not only by his abilities and loyalty to the tsar, but also by an overly intimate relationship with Peter.

Peter the Great’s Homoerotic Eccentricities

Sources preserve quite a few details about Peter the Great’s homoerotic eccentricities. Here are several vivid episodes.

Villebois wrote that Peter “was prone, so to speak, to fits of amorous fury, during which he did not distinguish between the sexes.”

Andrei Nartov claimed that Peter could not sleep alone. If his wife was not nearby, he would call the first orderly he came across into bed. An orderly (Russian denshchik) was a soldier-servant assigned to an officer or to the tsar. According to Nartov, Peter suffered from nocturnal seizures, and he often fell asleep hugging the orderly Prokofy Murzin, gripping his shoulders with both hands.

“The sovereign truly did at times, during the night, have such convulsions in his body that he would have the orderly Murzin lie with him, and, holding onto his shoulders, would fall asleep — which I myself also witnessed.”

— Andrei Nartov

Murzin later made a career for himself and rose to the rank of colonel.

Jacob von Stählin recounted an even stranger episode. While resting outside the city, Peter supposedly used an orderly as a pillow: he ordered the man to lie on the ground and laid his head on the man’s belly. And he set a condition: the servant had to be hungry. If the stomach growled, Peter would become irritated and might strike him.

There is another cluster of stories, too: Peter, it is said, openly displayed affection toward his close associates — hugging them, stroking their heads, showering them with kisses. The orderly Afanasy Tatishchev could receive “a hundred kisses” from him in a single day.

Bergholz once noted in his diary that the sovereign had acquired a new favorite — the young Vasily Pospelov. Pospelov sang in the royal choir, and his voice pleased Peter. Peter himself liked to sing and could step into the choir alongside the singers. According to Bergholz, Pospelov so captivated him that the tsar almost never parted from him, lavished him with caresses, and made the highest dignitaries wait until he had finished talking with his beloved.

“It is astonishing how great lords can even become attached to people of every sort. This man is of low origin, brought up like all the other choristers, very unattractive in appearance and, as everything suggests, simple — even stupid — and yet the most eminent people in the state court him.”

— Friedrich Wilhelm Bergholz on Vasily Pospelov and Peter the Great

Favorites and Favoritism

Favoritism is a system in which a monarch’s close associates receive a special status and privileges. The word came from French, and its root is Latin: favor — “goodwill,” “favor.” Sometimes such people could be lovers, but not necessarily: a favorite is above all someone the sovereign trusts and singles out.

Favoritism is not merely personal liking. It is a mechanism of power. Favorites received ranks, awards, money, lands, and access to decision-making. They could be friends, comrades-in-arms, administrators, and sometimes — intimate partners.

At Peter’s court, three men stood out in particular: Romodanovsky, Sheremetev, and Menshikov. The first two enjoyed an exceptional privilege — they could enter the tsar’s chambers at any time, even at night. Peter treated them with demonstrative respect and personally saw them to the door.

In the 18th century, favoritism in Russia reached its peak. One of the most striking favorites was Alexander Danilovich Menshikov — Peter’s closest associate.

Alexander “My Heart” Menshikov

The first mention of Menshikov in surviving sources dates to 1698. The Austrian diplomat Johann Korb called him “the tsar’s favorite, Menshikov, from the lowest sort of people.” At the same time, Menshikov’s origin remains disputed to this day: either he truly was a commoner, or he came from a noble Polish family, the Menzhikovs — both versions exist.

Menshikov was born in 1673 — a year after Peter the Great. Contemporary descriptions portray him as tall and strongly built, with striking facial features. According to legend, in his youth he sold pies until Franz Lefort noticed him — one of the young tsar’s closest associates, a “European” at court, and an organizer of many of Peter’s initiatives.

In the late 1680s, Menshikov found his way to court and became Peter’s orderly. An orderly to the tsar was not just a servant: it was a person who was constantly nearby, helped in everyday life, accompanied the tsar, guarded him, carried out personal errands, and also often took part in the tsar’s drinking feasts. In that last role, Menshikov excelled.

“[Menshikov] owes all his fortune to the tsar’s favor, for the tsar loves him, while he is the object of envy and hatred among the Russian nobility, having nothing to set against them except the protection of his sovereign.”

— A. de Lavi, French consul for maritime affairs, on Alexander Menshikov

During the Great Northern War, Menshikov took part in the assault on Nöteborg and the siege of Nyenschantz — fortresses on the Neva and around it, key points in the struggle with Sweden for access to the Baltic.

For his military service he received the post of governor of the Saint Petersburg Governorate. In practice this meant that he ran the region around the new capital. Menshikov directed the building of Saint Petersburg, Kronstadt, shipyards, and factories. He was even entrusted with the upbringing of Peter’s son.

“In general, he [Peter] only pretends to be a supporter of legality, and when some injustice is committed, the prince [Menshikov] need only draw the hatred of those harmed onto himself… And people say of the tsar that he himself is kind, while the blame falls on the prince in many matters in which he is often innocent…”

— the Danish envoy Just Juel on Peter the Great and Menshikov

Menshikov’s real fame came after the Battle of Poltava. It was his actions that prevented the Swedish king Charles XII from striking the Russian camp by surprise — and this became one of the keys to victory. After Poltava, Menshikov was no longer merely “a man at the tsar’s side”: he headed the Military Collegium (the main body overseeing the army), entered the Senate, and accumulated a whole array of top posts.

“Menshikov was conceived in lawlessness, and in all sins his mother bore him, and in trickery he will end his life.”

— Peter the Great on Alexander Menshikov

But Menshikov needed more than power as a tool. He greedily collected titles, money, and honors. He was called Russia’s greatest embezzler — a man who stole from the state treasury on an enormous scale.

He dressed with ostentatious luxury: his caftans glittered with diamonds, like those of European monarchs. And he did not hesitate to beg for symbolic marks of recognition: for example, he pestered Isaac Newton for the title of honorary fellow of the British Academy (i.e., election to an elite learned society), even though, according to contemporaries, he could barely write.

By the 1720s, in influence he was second only to Peter. Where the tsar was absent, decisions were often made through Menshikov — or by him.

“In everything that concerns honors and profit, he appears the most insatiable of creatures ever born.”

— the Danish envoy Just Juel on Alexander Menshikov

On February 8, 1725, Peter the Great died and left no will. Menshikov acted quickly: he helped Catherine take the throne. But Catherine was often ill, and among the nobility dissatisfaction grew with the “favorite” — a temporary strongman who had taken too much for himself. The opposition rallied around the young Peter II and waited for a convenient moment.

In the spring of 1727, Catherine died. Menshikov persuaded her to pass the throne to Peter II, but on one condition: the new emperor had to marry his daughter. That was agreed. Menshikov moved the young tsar into his own palace and began building him a new one — a demonstrative gesture of power: “the sovereign lives in my house, therefore I am the chief.”

But Peter II adored hunting and trips into the countryside. There his circle quickly pulled the boy away from Menshikov. In the end, the tsar turned away from his former mentor and broke off the engagement.

“I myself have many enemies. To destroy me, what would Empress Eudoxia not be capable of? What am I not suspected of! How many times have I been the victim of the ungrateful, whose happiness I arranged! I stand only one step from the abyss… His [Peter’s] son despises me, the streltsy scorn me. The patriarch considers me the sole culprit in his downfall; the clergy fear and curse me; the boyars hate me. I may be guilty. If we lose a battle, if the tsar lacks either troops or money, everyone says that I urged him to use the soldiers elsewhere, and that I spent the money on myself. They even dare to accuse me of building Saint Petersburg. I am surrounded by the envious and by enemies, and it would be a wonder for me myself if I escape exile.”

— Alexander Menshikov

The Supreme Privy Council stripped Menshikov of everything: offices, titles, wealth, and power. He was exiled to Siberia.

On the way, his wife Darya died. At Christmas 1728, on her eighteenth birthday, his daughter Maria died — the very one who was supposed to become empress.

In November 1729, Menshikov himself died as well. He was buried in permafrost, but later the riverbank collapsed, and the spring flood carried his remains away. Later, Empress Anna Ivanovna returned his children from exile.

Menshikov and Peter the Great

Menshikov had a rare quality: he perfectly matched Peter’s idea of what a “new” loyal man in power should be. Smart, quick, energetic, brave, physically strong, tough on subordinates — and at the same time able to get along with people. He was not vindictive and could drink “without end.” There were few men like that, and Peter forgave him a great deal.

Peter genuinely felt sincere affection for him. They fought together, built together, endured the harsh grind of campaigning together. Menshikov was constantly at his side — on the battlefield, at the tsar’s table, and at moments when the fate of the state was being decided.

In 1703 their bond received symbolic confirmation: on the same day, both of them received Russia’s highest award — the Order of St. Andrew the Apostle.

It was precisely this closeness that became fertile ground for talk that their relationship might have gone beyond ordinary friendship and service.

The Correspondence of Menshikov and Peter the Great

Peter addressed Menshikov with striking warmth. He called him Alexashka — a friendly nickname, though Peter could give such nicknames to others as well.

The difference lay elsewhere: it was Menshikov, specifically, to whom he wrote “my heart” and “my heartfelt brother and companion.” The letters also contain German phrases: “mein Herzenskind!” (“my heart’s child”), “mein bester Freund” (“my best friend”), “mein Bruder” (“my brother”).

Menshikov, too, replied very freely, without the usual courtly groveling. For example, Field Marshal Sheremetev signed off in a deliberately humble way: “your most obedient slave.” But Alexashka wrote simply, comrade to comrade: “My Lord Captain, hello!” — and put down only his name. “Captain” here is not mere formality: Peter liked to “play at military roles” and demanded that people address him by rank even when he was tsar.

Here are several of Peter’s letters to Menshikov:

“Mein Herz.” [My heart.]

We have been here as per your word, thank God, and have had plenty of fun, leaving not a single place untouched. By the blessing of the Metropolitan of Kyiv, we named the town together with its ramparts and gates, about which I am sending a drawing with this letter. And at the blessing we drank at Gate 1 wine, at Gate 2 sekt (sparkling wine), at Gate 3 Rhine wine, at Gate 4 beer, at Gate 5 mead, and at the gate Rhine wine — about which the bearer of this letter will report more fully. All is well; only grant, grant, grant, O God, that I may see you in joy. You know yourself.

We finished the last gate — the Voronezh Gate — with great joy, remembering what is to come.”

— Peter the Great, in a letter to Alexander Menshikov, February 3, 1703

“Mein liebster Kamerad.” [My dearest comrade.]

I earnestly ask that from fifteen to twenty of the best gunners be sent with this messenger; I repeat my request. Of my life here I do not wish to write to you: God grant that I may see you in joy.”

— Peter the Great, in a letter to Alexander Menshikov, July 7, 1704

“I would have been with you long ago, but for my sins and misfortunes I have remained here in this manner: on the very day of my departure from here, a fever seized me.

[…] as much from the illness, and even more from sorrow that time is being lost, and also from being separated from you. For this reason we commend you to God’s keeping, and I remain.

Grant, grant, grant, O Lord God, that I may see you in joy. Please give my greetings to our friends and acquaintances.”

— Peter the Great, in a letter to Alexander Menshikov, May 8, 1705

“Earlier I wrote to you of my distress, and that I would write to you again; of which I now inform you that, by God’s mercy, it is easing, and by the signs it appears to be turning to the good; however, God knows how soon it will leave. In this illness, the anguish of separation from you is no less — which I have many times endured within myself; but now I can endure no longer: come to me as soon as you can, so that I may be more cheerful — you yourself can judge why. Also take the English doctor and come here with a small party.”

— Peter the Great, in a letter to Alexander Menshikov, May 14, 1705

Punishment for Talking About the Tsar’s Alleged Affairs with Men

Menshikov — a man who started “from the bottom” and rose to the very top of power with astonishing speed — inevitably became a magnet for rumors. The closer he was to the tsar, the more readily people explained his success by “other reasons.”

Among ordinary people, talk was already circulating about a possible sexual intimacy between Peter the Great and Menshikov. Court records make this visible: documents preserved in the Russian State Archive of Ancient Acts (RGADA) contain statements in which the accused spoke of the sovereign’s “unnatural” inclinations.

1. The Case “On the Merchant Gavrila Romanov” (RGADA. F. 6. Op. 1. D. 10).

In 1698, the merchant Gavrila Romanov — who was not a member of the ruling Romanov dynasty, but merely a namesake — was accused of “reviling” the tsar, that is, speaking insulting words about the sovereign. The witness was Fadeika Zolotaryov. He testified that during Cheese Week (Maslenitsa — the week before Great Lent), when Romanov was visiting him, Romanov said:

— The Sovereign’s favor toward Menshikov is such as no one else has.

Zolotaryov tried to explain this “in a decent way” — as God’s help and the power of Menshikov’s prayers. But Romanov, according to him, answered differently, and far more dangerously:

— God had nothing to do with it. The devil carried him [Peter] off with him — he lives with him in fornication and keeps him in his bed like a wife.

At interrogation, Romanov denied everything. He insisted that Zolotaryov had slandered him over an old debt: the creditor was allegedly trying to squeeze money out of him — with persuasion and with threats.

Trying to save himself, Romanov decided to bribe Menshikov himself: he sent his grandson and a servant to Menshikov with a small barrel of money. But in Menshikov’s house they were caught by the tsar in person. The messengers were arrested.

At a new interrogation, Romanov said he was gravely ill, had already confessed, and wanted to die at home rather than in custody. Soon he really did die, and the investigation was closed.

Even so, the episode matters: the case shows that talk about a “peculiar closeness” between Peter and Menshikov already existed — and so openly that it could become grounds for a political investigation.

2. The Case “On Denunciations [Slander] by Prisoners Held in the Vologda Jail” (RGADA. F. 371. Op. 2, part 4. Art. 734).

In 1703, in Vologda, two prisoners accused an exiled soldier, Ivan Rokotov, of dangerous words about the tsar — essentially, a political crime. The denunciation ran like this: several years earlier in prison, Rokotov had allegedly repeated the words of another exile — Nikita Seliverstov. According to the informants, Seliverstov had served under Captain Mikhaylo Feoktistov.

Rokotov, they claimed, said that Seliverstov had spoken of the tsar as follows:

— What kind of tsar is he? He’s no tsar, he’s an impostor, and he lives with Menshikov in fornication, and that’s why he favors him.

When Seliverstov heard the accusation, he rejected it. More than that: he said the original source of the words was the informer himself. Supposedly, during the Azov campaign the informer had seen everything with his own eyes:

— …he was standing guard by the Sovereign’s tent, and the Sovereign, walking about in nothing but a shirt, kisses Alexander [Menshikov], and after kissing him, lies down to sleep with him.

After that, the case turned into torture. Investigators tortured Seliverstov twice, but he held to his story: the denunciation was revenge for old prison conflicts. How it ended is not clear from these materials.

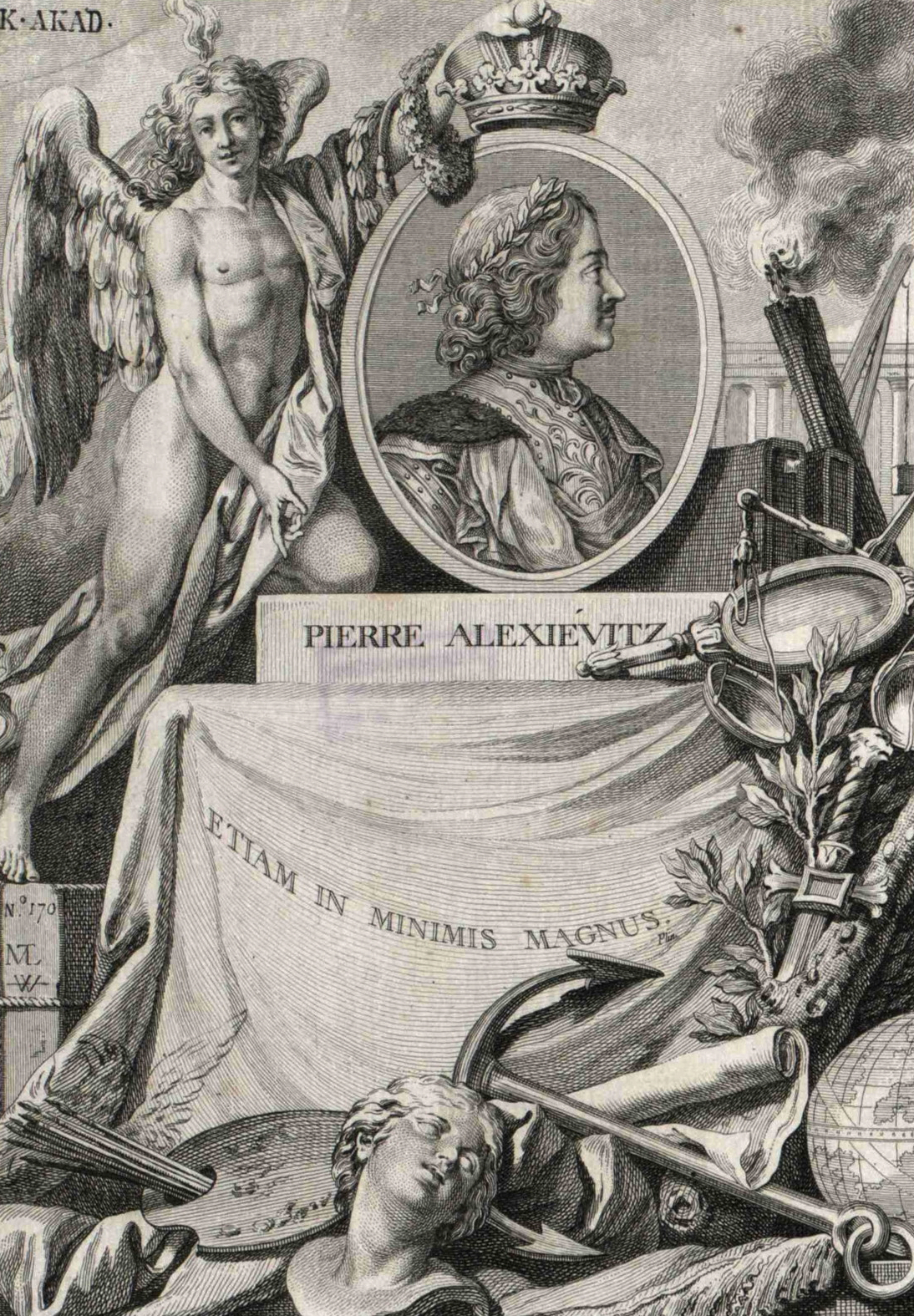

![Alexey Venetsianov, “Peter the Great: The Founding of Saint Petersburg” [with Menshikov]](/images/courses/russian-queer-history/18-peter-14.jpg)

Introducing Punishment for “Sodomy” in the Army Under Peter the Great

This looks paradoxical: under Peter the Great, rumors circulate about the tsar’s intimacy with men — and under him, the first state punishments for “sodomy” appear as well. But the explanation here is practical.

Peter was building an army “the European way” and pulling Russia toward the norms he saw in Europe. In a number of European countries, laws against same-sex relations already existed — so, in Peter’s logic, something similar should exist in his state too. At first, this applied only to the military: the army was the main testing ground for new rules.

Enforcing such an order was assigned to Menshikov. In 1706, he issued the “Short Article” (a short military code of rules and punishments). There, for the first time, a punishment was explicitly set for “unnatural acts of adultery” — a legal euphemism of the period for same-sex acts and sexual abuse of minors. For male same-sex intercourse or the “corruption” of children, the penalty threatened was burning at the stake, but it never came to real executions. About ten years later, the punishment was softened: in the Military Regulations of 1716 (the Armed Forces’ statutory code), the death penalty was replaced with corporal punishment.

More on this — in a separate piece:

The Causes of Peter’s Death: Syphilis or Something Else?

There was a lot of talk about Peter’s health in his final years. In 1721, the Polish envoy Johann Lefort wrote:

“The Tsar’s health grows worse with each passing day; shortness of breath troubles him greatly. They suppose he has an internal abscess which from time to time opens, and I heard that his latest pain in the throat was from matter flowing from the abscess; moreover, he does not take the slightest care of himself.”

— Johann Lefort, Polish envoy, on Peter the Great’s health (1721)

Courtiers also noticed strange coincidences: one of the pages fell ill at the same time as the tsar. The page was not especially handsome, but even this fueled additional rumors about a possible connection.

The syphilis version appeared back in the 18th century. But at the time, doctors did not clearly distinguish syphilis from gonorrhea: both diseases could be described using the same words and symptoms. No official autopsy report of the tsar has survived.

In 1970, specialists at the Central Institute of Dermatovenereology (a medical field focused on skin and sexually transmitted infections) studied the available materials and concluded that the cause of death was urosepsis. This is a severe infection that develops from urinary-tract problems: an obstruction forms, inflammation intensifies, and the body goes into acute kidney failure. According to descriptions, Peter suffered from intense pain and serious urinary dysfunction; the illness progressed rapidly and became fatal.

At the same time, Peter clearly understood the danger of venereal diseases. In the hospitals established under him, special wards appeared for infected soldiers. Under him, Russia opened 10 large hospitals and more than 500 field infirmaries.

Conclusion

Sometimes people want to “touch up” Peter the Great’s image and make him seem even more unusual — for example, by adding new versions of his private life. But you can’t build confident conclusions on guesses. History as a discipline rests on caution and fact-checking: what matters is not pretty theories in themselves, but the ability to assess sources soberly and rely only on what is genuinely confirmed.

One of the strengths of historical research is that it teaches us to doubt — and not to pass conjecture off as truth.

Most likely, we will never learn the whole truth about Peter the Great’s private life. There are many rumors and hints around him, but there is no direct evidence of possible bisexuality. And the indirect signs that people sometimes cite are scattered and allow for different explanations — so they can’t be interpreted unambiguously.

At the same time, it’s also strange to “zero out” such hints completely and say there is simply nothing to discuss. That leaves two extremes: either believing everything unconditionally, or denying everything outright. Both positions are unreliable.

The conclusion is simple: Peter the Great may have been bisexual — and he may not have been. Given the data we have, the most honest way to put it is this: the version is possible, but unproven. The right stance here is not to proclaim it “certain truth,” but also not to ban the question itself — as long as it’s discussed carefully and with reliance on sources.

To close, here are three views of Peter: negative, neutral, and laudatory.

“A raging, drunken beast, rotted by syphilis, for a quarter of a century ruins people, executes them, burns them, buries people alive, imprisons his wife, debauches himself, commits sodomy, drinks, and, amusing himself, chops off heads; he blasphemes, rides about with a mock cross made of pipe-stems shaped like male genitals and mock Gospels — a box of vodka to ‘praise Christ,’ that is, to sneer at the faith; he crowns his whore and his lover, devastates Russia, executes his son, and dies of syphilis — and not only do they fail to remember his atrocities, they still do not cease praising the virtues of this monster, and there is no end to monuments of every kind to him.”

— Leo Tolstoy on Peter the Great

“A barbarian who civilized his Russia; he who built cities but did not want to live in them; he who punished his wife with the knout (a heavy whip used for corporal punishment) and granted women broad freedom — his life was great, rich, and useful in public terms, but in private terms it was whatever it happened to become.”

— August Strindberg on Peter the Great

“Whom shall I compare the Great Sovereign to? In antiquity and in modern times I see rulers called great. And truly, they are great before others. Yet before Peter they are small. … To whom shall I liken our hero? I often pondered what He is like who, with almighty gesture, governs heaven, earth, and sea: He breathes His spirit — and the waters will flow; He touches the mountains — and they will rise in smoke.”

“He was a god, he was your god, Russia!”

— Mikhail Lomonosov on Peter the Great

🇷🇺 This piece is part of the article series “LGBT History of Russia”:

- Homosexuality in Ancient and Medieval Russia

- A Cross-Dressing Epic Hero: the Russian Folk Epic of Mikhaylo Potyk, Where He Disguises Himself as a Woman

- The Homosexuality of Russian Tsars: Vasily III and Ivan IV “the Terrible

- Uncensored Russian Folklore: Highlights from Afanasyev’s “Russian Secret Tales

- Homosexuality in the 18th-Century Russian Empire — Europe-Imported Homophobic Laws and How They Were Enforced

- Peter the Great’s Sexuality: Wives, Mistresses, Men, and His Connection to Menshikov

- Russian Empress Anna Leopoldovna and the Maid of Honour Juliana: Possibly the First Documented Lesbian Relationship in Russian History

- Grigory Teplov and the Sodomy Case in 18th-Century Russia

- Russian Poet Ivan Dmitriev, Boy Favourites, and Same-Sex Desire His the Fables ‘The Two Doves’ and ‘The Two Friends’

- The Diary of the Moscow Bisexual Merchant Pyotr Medvedev in the 1860s

- Maslenitsa Effigy: The “Man in Women’s Clothes” of Russia’s Pre-Lent Carnival

- Sergei Romanov: A Homosexual Member of the Imperial Family

- Andrey Avinoff: A Russian Émigré Artist, Gay Man, and Scientist

📣 Subscribe to our Telegram channel (in Russian): Urania. With Telegram Premium, you can translate posts in-app. Without it, many posts link to our website, where you can switch languages — most new articles are published in multiple languages from the start.

References and Sources

- Анисимов Е. Толпа героев XVIII века. 2022. [Evgenii Anisimov - A Crowd of Heroes of the 18th Century]:

- Анисимов Е. В. Петр Великий. 1999. [Evgenii V. Anisimov - Peter the Great]:

- Беспятых Ю. Н. Александр Данилович Меншиков: мифы и реальность. 2005. [Yuri N. Bespyatykh - Alexander Danilovich Menshikov: Myths and Reality]:

- Берхгольц Ф. В. Дневник камер-юнкера Берхгольца, веденный им в России в царствование Петра Великого. 1993. [Friedrich Wilhelm Bergholz - Diary of Chamber-Juncker Bergholz, Kept in Russia during the Reign of Peter the Great]:

- Грунд Г. Доклад о России в 1705–1710 годах. 1992. [G. Grund - Report on Russia in 1705–1710]:

- Карлинский С. «Ввезен из-за границы»? Гомосексуализм в русской культуре и литературе. В кн.: Эротика в русской литературе от Баркова до наших дней. 1992. [Simon Karlinsky - “Imported from Abroad”? Homosexuality in Russian Culture and Literature]:

- Кротов П. А. Подлинные анекдоты о Петре Великом Я. Штелина (у истоков жанра исторического анекдота в России). Научный диалог. 2021. [Pavel A. Krotov - Authentic Anecdotes about Peter the Great by J. Stählin (At the Origins of the Genre of Historical Anecdote in Russia)]:

- Куракин Б. И. Гистория о царе Петре Алексеевиче (1628–1694). В кн.: Петр Великий. 1993. [Boris I. Kurakin - History of Tsar Peter Alekseevich (1628–1694)]:

- Куракин Б. И. Гистория о царе Петре Алексеевиче. В кн.: Россию поднял на дыбы… 1987. [Boris I. Kurakin - History of Tsar Peter Alekseevich]:

- Павленко Н. И. Петр Великий. 1990. [Nikolai I. Pavlenko - Peter the Great]:

- Павленко Н. И. Меншиков: полудержавный властелин. 2005. [Nikolai I. Pavlenko - Menshikov: The Semi-Sovereign Ruler]:

- Петр Великий. Письма и бумаги императора Петра Великого. Т. 1 (1688–1701). 1887. [Peter the Great - Letters and Papers of Emperor Peter the Great. Vol. 1 (1688–1701)]:

- Петр Великий. Письма и бумаги императора Петра Великого. Т. 2 (1702–1703). 1888. [Peter the Great - Letters and Papers of Emperor Peter the Great. Vol. 2 (1702–1703)]:

- Петр Великий. Письма и бумаги императора Петра Великого. Т. 3 (1704–1705). 1893. [Peter the Great - Letters and Papers of Emperor Peter the Great. Vol. 3 (1704–1705)]:

- Петр Великий. Письма и бумаги императора Петра Великого. Т. 4 (1706). 1900. [Peter the Great - Letters and Papers of Emperor Peter the Great. Vol. 4 (1706)]:

- Порозовская Б. Д. А. Д. Меншиков. Его жизнь и государственная деятельность. В кн.: Петр Великий, Меншиков и др. 1998. [B. D. Porozovskaya - A. D. Menshikov: His Life and State Activity]:

- Андреева Е. А. А. Д. Меншиков – «полудержавный властелин» или балансирующий на краю пропасти? Меншиковские чтения. 2011. [E. A. Andreeva - A. D. Menshikov: “Semi-Sovereign Ruler” or Balancing on the Edge of the Abyss?]:

- Губергриц Н. Б. Болезнь и смерть Петра Великого: только ли урологические проблемы? Гастроэнтерология Санкт-Петербурга. 2020. [N. B. Gubergrits - The Illness and Death of Peter the Great: Only Urological Problems?]:

- Дипломатические документы, относящиеся к истории России в XVIII столетии. В кн.: Сборник Императорского русского исторического общества. 1868. [Imperial Russian Historical Society - Diplomatic Documents Relating to the History of Russia in the 18th Century]:

- Ефимов С. В. Болезни и смерть Петра Великого. В кн.: Ораниенбаумские чтения. 2001. [S. V. Efimov - Diseases and Death of Peter the Great]:

- Записки Юста Юля, датского посланника при Петре Великом (1709–1711). [Just Juel - Notes of Just Juel, Danish Envoy to Peter the Great (1709–1711)]:

- Корб И. Г. Дневник поездки в Московское государство Игнатия Христофора Гвариента, посла императора Леопольда I, к царю и великому князю московскому Петру Первому в 1698 году, веденный секретарем посольства Иоанном Георгом Корбом. В кн.: Рождение империи. 1997. [Johann Georg Korb - Diary of a Journey to the Muscovite State (1698)]:

- Мухин О. Н. Царь наш Петр Алексеевич свою царицу постриг, а живет блудно с немками: гендерный облик Петра I в контексте эпохи. Вестник Томского государственного университета. 2011. [Oleg N. Mukhin - “Our Tsar Peter Alekseevich Tonsured His Tsarina, and Lives in Debauchery with German Women”: The Gender Image of Peter I in the Context of the Era]:

- Рассказы Нартова о Петре Великом. В кн.: Петр Великий: предания, легенды, анекдоты, сказки, песни. 2008. [Andrei Nartov - Nartov’s Stories about Peter the Great]:

- Щербатов М. М. Рассмотрение о пороках и самовластии Петра Великого. В кн.: Петр Великий: Pro et contra. 2001. [Mikhail M. Shcherbatov - An Inquiry into the Vices and Autocracy of Peter the Great]:

- Шишкина К. А. Становление и особенности института фаворитизма в России в XVIII веке на примере личности А. Д. Меншикова. В кн.: Students Research Forum 2022: сборник статей Международной научно-практической конференции. 2022. [K. A. Shishkina - The Formation and Features of Favoritism in 18th-Century Russia on the Example of A. D. Menshikov]:

- Зимин И., Grzybowski A. Peter the Great and sexually transmitted diseases. Clinics in Dermatology. 2020.

- Villebois G. E. Memoirs secrets pour servir à l’histoire de la Cour de Russie, sous le règne de Pierre le Grand et de Catherine Ire. 1853. [G. E. de Villebois - Secret Memoirs to Serve the History of the Court of Russia, under the Reign of Peter the Great and Catherine I]:

- Weber F. C. The Present State of Russia. 2021.

- Tags:

- Russia