Adam Before Eve: Male or Androgynous? Theological Debates From the Church Fathers to the Present Day

A full, detailed queer-theological analysis of the theory that Adam was androgynous.

- Editorial team

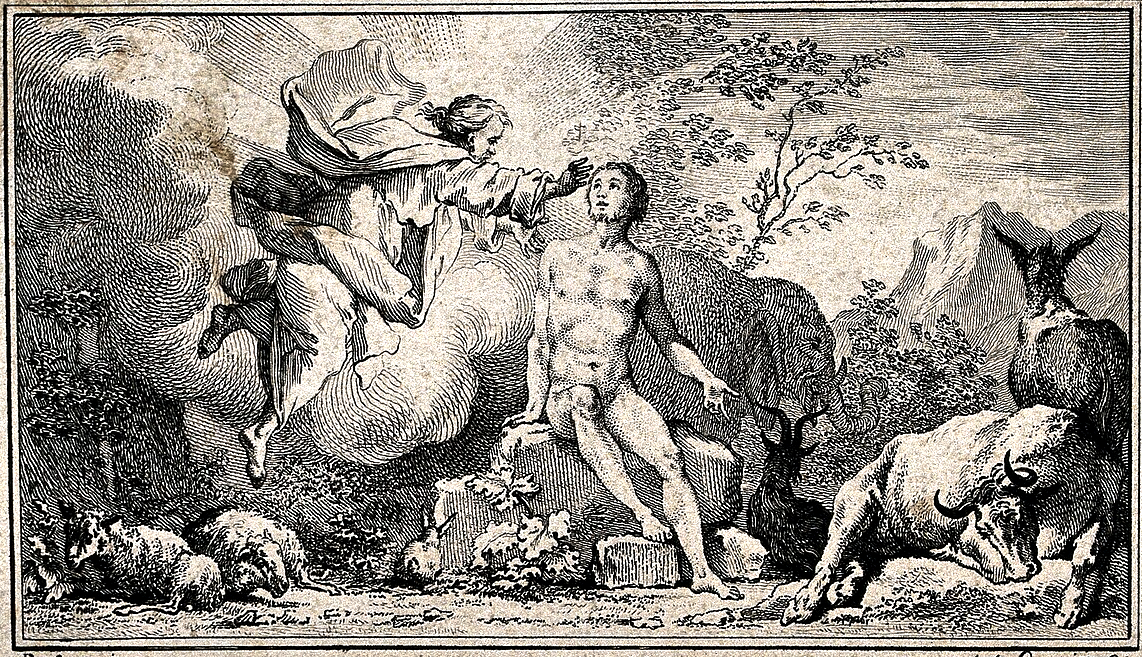

In Genesis 2, God creates Eve from Adam’s rib. This prompts a basic question: what was Adam’s sex or gender status before Eve appeared — at a moment when “woman,” as a socially and linguistically formed category, has not yet entered the narrative?

Only a small number of authors who discuss this episode in detail point to a possible clue in Genesis 1–2: before Eve’s creation, Adam may have been understood as an androgynous being. Androgyny is typically defined as the combination of male and female traits within a single person; on this reading, Adam before Eve could be described as two-sexed, meaning that both male and female characteristics were present in one body.

A different interpretation is also proposed: the first human may have had no sex at all, and the differentiation into man and woman occurred later — as the story progressed. At the same time, the androgynous hypothesis has critics who reject this reading and offer alternative explanations.

This article reviews the debate on both sides — the arguments advanced by proponents of an androgynous interpretation and the objections raised by their opponents.

Two Accounts of the Creation of Humanity in the Bible

Genesis contains two distinct descriptions of the creation of humanity. In the first chapter, God creates humankind simultaneously:

“So God created man [adam = humankind] in His own image; in the image of God He created him; male and female He created them.”

In the second chapter, the sequence differs: first a man is created, and the woman appears later — from his rib:

“And the LORD God caused a deep sleep to fall on Adam, and he slept; and He took one of his ribs, and closed up the flesh in its place. Then the rib which the LORD God had taken from man [adam] He made into a woman, and He brought her to the man.

And Adam said: ‘This is now bone of my bones And flesh of my flesh; She shall be called Woman, Because she was taken out of Man.’”

These differences are apparent in both content and style, and they have long drawn scholarly attention. In modern biblical studies and theology, a common explanation is that Genesis developed from multiple traditions that were later combined into a single text. The documentary hypothesis is grounded in this assumption. It does not claim definitive proof, but it proceeds from the idea that different parts of Scripture may derive from different sources.

The first chapter is often associated with the Priestly source. In this section, God is designated by the term “Elohim” (a Hebrew divine name). The second chapter is frequently linked to the Yahwist tradition, where the combined form “Yahweh Elohim” appears — that is, “the Lord God” (“Yahweh” is the personal divine name in the Hebrew Bible).

The structure of these passages also differs. The first chapter is strict and rhythmic, resembling a step-by-step account: over six days, God creates light, dry land, plants, and animals, and then — the human being. It is a cosmological narrative oriented toward the world as a whole.

In the second chapter, the focus shifts to the human being and the immediate environment: Adam appears, then Eve; the Garden of Eden is introduced; and the first interactions between the human and the animals are described.

On the Meaning of the Word “Adam”

The Brown–Driver–Briggs Hebrew lexicon distinguishes three primary meanings of the ancient Hebrew term ’ādam. First, it can mean “a man.” Second, it can mean “humankind as a whole.” Third, it can function as the proper name “Adam,” referring to the first human being.

In biblical texts, ’adam frequently appears with the definite article ha-, forming ha-adam. This expression is often translated as “the human” or “humankind” (literally, “the human”). It occurs especially often in the creation narrative set in the Garden of Eden.

In the early 21st century, the American Orthodox rabbi Pinchas Stolper examined this term in a series of articles. He focused on Genesis 2:18: “And the Lord God said, it is not good for ha-adam to be alone; I will make for him a helper corresponding to him.” This raises a question: who, precisely, is meant by ha-adam?

For Stolper, the referent is not ’ish (“man” in the sense of male) and not adam understood narrowly as “a male man,” but a distinct kind of being. In his reading, its nature is clarified by Genesis 1:27: “And God created ha-adam in His image; male and female He created them.” Like many Jewish thinkers before him, Stolper treats this verse as layered. First, ha-adam is presented as a single whole. Next, the text specifies that both the male and the female principles were originally present within this being. Only at a third stage does division come into view, when from one image two emerge — “them.”

This represents one stream within Jewish tradition. The next question is how Christian authors approach the same issue.

Two Perspectives: Traditionalist and Egalitarian

From the earliest centuries of Christianity, the idea of an originally androgynous human drew attention and became a point of dispute. The Church Fathers discussed it already, but debate intensified in the 1980–1990s, especially within evangelical contexts. Over time, two broad positions became prominent: traditionalist and egalitarian.

Traditionalists reject the idea of an androgynous Adam. In their view, God created man and woman from the beginning as distinct beings with different, yet complementary, roles. A notable representative of this approach is the American Protestant pastor Raymond Ortlund Jr., who articulated complementarianism — the view that men and women are equal in dignity before God, yet differ in calling and role as embedded in the order of creation.

Ortlund argued that male headship and the equality of the sexes are not contradictory, but coexist within a single framework. He appealed to the opening chapters of Genesis, where adam can mean both “human” and “man.” For Ortlund, this semantic range supports a particular role for the male as source and head in relation to the woman.

Egalitarians frame the question differently. For them, the cultural setting and linguistic features of the biblical texts are central. Ancient Hebrew developed within a patriarchal society in which men occupied leading positions; as a result, masculine grammatical forms were often used to refer to humanity as a whole. Egalitarians tend to treat this as an artifact of historical context rather than a direct statement of divine intent.

In addition, some egalitarians (not all of whom are feminist authors) argue that the human becomes fully complete only with the appearance of the woman. On this reading, she is not a secondary being, but the completion of creation.

These debates renewed interest in alternative accounts of the first human. Increasingly, authors began to consider hypotheses of a sexless Adam or an androgynous Adam.

The Androgynous Theory

Genesis 1 states: “God created the human being in His image… male and female He created them” (Genesis 1:27). In some early Jewish interpretations, this phrasing was read as an indication that the human being was originally conceived as a single, unified creature — an androgyne. On this view, God later divided that one being into two sexes.

Genesis 2 presents a different sequence: Adam is placed into a deep sleep, and God creates a woman from his rib. At first glance, the two accounts appear to be in tension. Many theologians, however, argue that there is no real contradiction: the first chapter speaks to the integrity of the human being as the image of God, while the second describes how that integrity unfolds into two distinct persons.

Within Christian tradition, this line of reading contributed to the idea of an androgynous Adam: the first human was a single being encompassing both sexes, and the emergence of man and woman became a way for one human nature to be expressed in two.

To trace the origins and later development of these ideas, we must examine the views of theologians, philosophers, and other thinkers — from the Church Fathers to modern proponents and critics of the androgynous theory.

In Favor of Adam’s Androgyny

The Church Fathers: Gregory of Nyssa and Maximus the Confessor

One of the earliest Christian authors to address the place of sex within God’s plan in a systematic way was Gregory of Nyssa — a 4th-century theologian and philosopher, venerated as a Church Father and saint. In On the Making of Man, he reflects on Genesis’s claim that the human being was created “in the image of God” and argues that the divine image contains no division by sex.

Appealing to Paul’s Letter to the Galatians (“there is no male and female”), Gregory maintains that the human being originally existed outside the “male/female” distinction. He writes:

“For Scripture first says, ‘God created the human being in the image of God,’ showing by these words — as the apostle says — that in such a one there is neither male nor female; and then it adds the distinguishing properties of human nature, namely: ‘male and female He created them.’”

— Gregory of Nyssa, On the Making of Man*

For Gregory, the human essence as the image of God does not initially include sexual differentiation; the division into two sexes belongs to the bodily dimension of nature. At the same time, God — foreseeing the Fall and mortality — provided in advance for reproduction through sexual division. Yet this “addition” is not part of the divine archetype and appears as the human condition moves closer to the animal world. In this sense, sex is treated as a temporary property of humanity.

On this basis, Gregory concludes that after the resurrection the difference between the sexes will disappear. The Gospel of Matthew states that the resurrected “neither marry nor are given in marriage; they are like angels in heaven.” For Gregory, this indicates the restoration of the original wholeness of human nature. It is important to clarify, however, that he does not claim Adam physically possessed both male and female organs at once. By “androgyny,” Gregory primarily means a spiritual condition of the human being before the Fall.

These themes were developed further by Maximus the Confessor. In Ambiguum 41, he describes the “male/female” distinction as the last of five fundamental “divisions” within creation. Christ removes these barriers, heals the world, and returns it to its original unity. According to Maximus, had Adam not transgressed the commandment, the continuation of the human race would have occurred by some other means — not in an “animal-like” mode (that is, not through biological, sexual reproduction). Here again, the focus is not physical androgyny, but the restoration of the “simple human being” in paradise, where sexual division loses its significance because it is bound up with death and corruption.

In the 9th century, this theme was continued by John Scotus Eriugena. In On the Division of Nature, he treats sexual difference as one instance of a broader rupture within the cosmos. In his view, at the beginning everything existed as one and remained in God; after the Fall, this integrity was fractured, and the human being found themself divided into man and woman.

According to Eriugena, had the human being not sinned, they would have lived in the knowledge of their true spiritual nature and would not have required reproduction “from two sexes,” like animals. Christ restores what has been divided to unity and reunites the human being with God, though final restoration, on this view, is possible only at the end of time.

Jakob Böhme and Franz von Baader

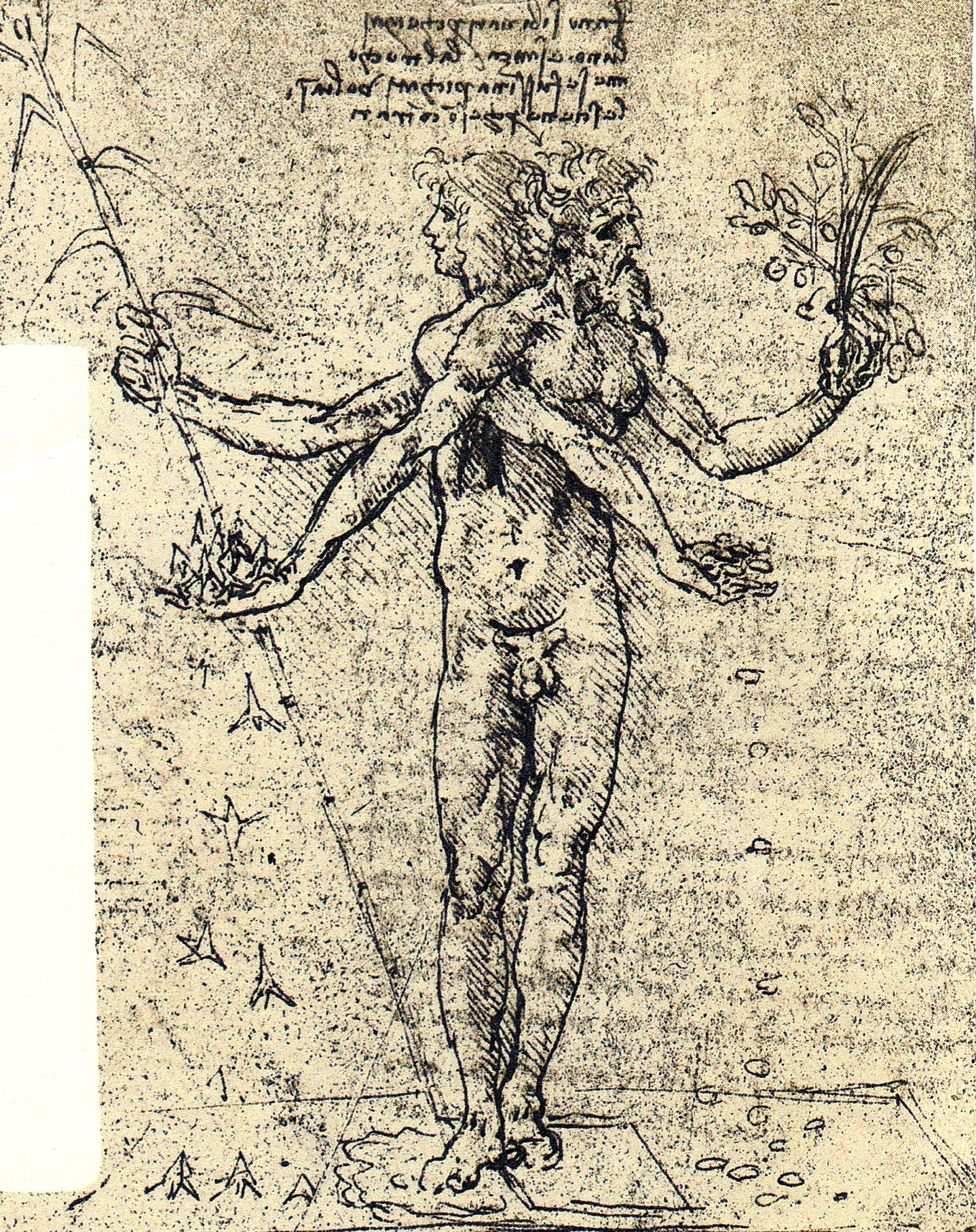

In the early 17th century, the German theosopher Jakob Böhme articulated a systematic account of an androgynous Adam. In his view, prior to the Fall, the human being was two-sexed: the masculine and feminine principles existed as an inseparable unity. Böhme describes this primordial human in intentionally vivid, figurative terms:

“Adam was a man, and likewise a woman, and yet at the same time neither this nor that, but a virgin, filled with chastity, purity, and innocence, as the image of God.”

— Jakob Böhme

On this reading, both principles were united in Adam in a perfect, virginal — that is, unfallen — form. Böhme associates this condition with two “tinctures” (a specifically Boehmian term for inner spiritual-energetic forces): a masculine, “fiery” tincture and a feminine, “luminous” tincture. Because these forces were balanced, the ideal Adam, according to Böhme, could generate offspring from within himself, without a partner.

Böhme interprets the Fall as a violent rupture of what had previously been whole. In his account, Adam, observing animals with differentiated sexes, desired the same arrangement for himself. This desire is treated as an expression of self-will. God then separated the feminine aspect from Adam and created Eve. At the same time, Adam lost his heavenly essence — Sophia (Divine Wisdom), the eternal “heavenly virgin.” As a result, Adam became only half of his former fullness, and Eve became an alienated part of that original unity.

For Böhme, redemption consists in the recovery of this lost integrity. Christ is the “new Adam,” in whom masculine and feminine principles are again joined in perfect unity. Within this framework, the Virgin Birth, Jesus’ celibacy, and His lack of any need for a spouse are understood as signs that an inner androgynous completeness was already present in Him. After the Resurrection, Böhme argues, human beings too will be able to restore the condition of the primordial Adam.

In the 19th century, the German philosopher-mystic Franz von Baader developed Böhme’s ideas along similar lines. He likewise held that the human being was originally androgynous and could generate life without division into two sexes. However, the Fall shattered this integrity:

“When Adam fell, he lost the feminine part of the virginal image, just as Eve lost the masculine. Since then, man and woman separately are only fragments, longing to be reunited.”

— Franz von Baader

In Baader’s philosophy, marriage therefore becomes a central theme. He treats it less as an instrument of procreation than as a spiritual sacrament aimed at restoring human wholeness. He calls Christian union a “small resurrection”: through love, spouses assist one another in overcoming one-sidedness, as the man discovers the feminine within himself, and the woman — the masculine.

“The goal of marriage is to return to husband and wife their original androgynous wholeness of the image of God.”

— Franz von Baader

Vladimir Solovyov, Nikolai Berdyaev, and Vasily Rozanov

The Russian philosopher Vladimir Solovyov revisited the theme of the androgyne in the late 19th century and gave it an ethical and religious significance. Familiar with the mystical thought of Franz von Baader and Jakob Böhme, he treated the androgyne as a symbol of humanity’s future perfection.

In his treatise The Meaning of Love, Solovyov argued that a person cannot be genuinely whole while remaining only a man or only a woman: fullness is possible only as the unity of two principles. Sexual love, in his account, is given not only for procreation but, above all, as a force that overcomes egoism and separation. In this sense, earthly love becomes a step toward restoring the integral image of God.

At the same time, Solovyov emphasized that he was not describing a physical fusion, but spiritual androgyny — an inner wholeness meant to be fully realized only at the end of history. He understood the Fall as the loss of this wholeness, and salvation as its recovery.

A central place in his philosophy was sophiology — a teaching on Divine Wisdom (Sophia). Solovyov linked Sophia’s “eternal femininity” to the androgynous theme: Sophia expressed the image of the transfigured Universal Soul, in which masculine and feminine principles are inseparable. These ideas shaped Russian religious thought in the early 20th century, giving the androgyne a Christian-romantic meaning: a call to transformative love and an anticipation of the future union of humanity into one human being in Christ.

Nikolai Berdyaev, developing impulses from Solovyov’s philosophy, formulated his own metaphysics of sex. He maintained that the image of God cannot be found in man or woman taken separately; it is disclosed only in the integral, androgynous human being:

“Neither man nor woman is the image and likeness of God, but only the androgyne, the integral human being. The differentiation of the masculine and the feminine is a consequence of Adam’s cosmic fall. The formation of Eve cast the old Adam under the power of species sexuality, chained him to the natural ‘world,’ to ‘this world.’ The ‘world’ caught Adam and possesses him through sex; at the point of sexuality Adam is fastened to natural necessity. Eve’s power over Adam became the power of all nature over him. The human being, bound to the Eve who gives birth, became a slave of nature, a slave of femininity — separated, differentiated from his androgynous image and likeness of God. The man tries to restore his androgynous image through sexual attraction to the lost feminine nature.”

— Nikolai Berdyaev, The Meaning of Creativity

Like Solovyov, Berdyaev interpreted love between the sexes as a desire to recover lost unity. Yet he argued that bodily passion more often produces conflict and misunderstanding than harmony. For him, the full overcoming of sexual division is possible only in the Kingdom of God.

Berdyaev also read Christ as the “Absolute Human Being” — a new, heavenly Adam in whom masculine and feminine principles are already reconciled. Accordingly, Jesus in his earthly life was a virgin “not because he denied love, but because he already embodied the integral, heavenly-androgynous Human Being.”

“Only the person who has restored their wholeness, their virginity, their androgynous image, can fully realize their creative vocation.”

— Nikolai Berdyaev, The Philosophy of Freedom

Within this framework, Berdyaev understood the Christian ideal of chastity not as a rejection of sex, but as an anticipation of renewed personhood beyond biological division.

Related motifs appear in Vasily Rozanov, a Russian Orthodox thinker of the early 20th century. He held that the first human being was an androgyne — a unified creature not yet divided into masculine and feminine. In his account, sex emerged later and was linked less to the Creator’s original design than to a system of moral prohibitions.

In People of the Moonlight, Rozanov wrote that sex is an integral magnitude from which the mutual attraction of man to woman and woman to man arises. He was troubled by a basic question: if reproduction is the fundamental law of nature, why did God initially create only one human being? He was likewise struck by the separation of Eve — whose name is translated as “mother of life” — from Adam. For Rozanov, this suggests that the feminine principle was already present in Adam. On this reading, the creation of Eve appears not as the beginning but as the completion of creation: she became, in his phrasing, “the last novelty” of the world.

A distinct theme in Rozanov’s reflections was homosexuality. He called the homosexual “a third human being beside Adam and Eve; in essence — that Adam from whom Eve has not yet come out; the first complete Adam. He is older than that first human being who began to reproduce.” In homosexuality, the philosopher saw a manifestation of an older layer of human nature, preceding the division of the sexes and the emergence of reproduction.

The Androgynous Adam in Modern Protestantism: Johannes de Moor, Phyllis Trible, Rebecca Groothuis

In the second half of the twentieth century, the hypothesis of an androgynous first human gained renewed attention in Protestant biblical scholarship. This shift was encouraged by gender studies, feminist exegesis, and broader philosophical debates of the period. Within these frameworks, some scholars proposed reading Genesis 1:27 as describing a two-sexed humanity — male and female at once. On this view, the verse could be paraphrased as: “God created it [humankind] as male–female.”

A central figure in these discussions was the Dutch scholar Johannes C. de Moor, a specialist in Semitic languages and the religions of the Ancient Near East. He argued that the author of Genesis 1 envisages the first human as an androgyne and directly links this condition to the image of God. Interpreting “image of God” in a strong, literal sense, de Moor extended the logic of androgyny beyond the human being to God Himself. In his reading, God is two-sexed.

To support this position, he appealed to Ancient Near Eastern religions, where creator deities often unite masculine and feminine principles within themselves. For de Moor, androgyny functions as a sign of the divine: it marks a boundary between the supernatural realm and the human world, in which the sexes are, by contrast, separated.

De Moor also emphasized the grammar of Genesis 1:27. In the verse, the forms “created him [humankind]” and “created them [male–female]” alternate. He suggested that the text may originally have used a pronoun in the dual number — a form indicating a pair rather than a plurality — and that this was later replaced by the plural “them.” He supported this claim with examples from other Semitic languages and with references to rabbinic commentary. On this account, “adam” in Genesis 1 functions as an androgynous being, simultaneously man and woman.

The American biblical scholar and one of the founders of feminist exegesis Phyllis Trible likewise argued that Genesis 1:27 presents the creation of Adam as simultaneously male and female within a single creative act. As evidence, she highlighted a detail in Genesis 2: even before Eve is created, the prohibition against eating from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil (Genesis 2:16–17) is directed not to a “man,” but to the entire creature (humankind) through the term “adam.” From this, Trible inferred that prior to the division into two sexes, Adam is imagined as androgynous.

As Trible observed, throughout Genesis 2 up to Genesis 2:23 the text uses only the word “adam.” Only then does Adam speak: “At last — bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh. She shall be called ishshah (woman), because she was taken out of ish (man).” (ishshah and ish are Hebrew terms: ishshah means “woman,” ish means “man.”) On this basis, Trible argued that an explicitly male designation appears only when the woman appears. In this narrative logic, the point of departure is androgyny, while sexual differentiation and the emergence of sexuality are associated with the creation of the woman. The “birth” of the woman is simultaneously the “birth” of the man: only in response to her does Adam name himself for the first time and recognize himself as male.

At the same time, Trible explicitly rejected the claim that the Yahwist account (Genesis 2–3) — in which Eve is formed from a rib — implies that woman is secondary or dependent. In her view, the climax of the narrative is precisely the creation of the woman: she is not a marginal element, but the culmination of the story. Trible linked this conclusion to the text’s structure. In Genesis 1, the human being appears last and functions as the crown of creation; similarly, in Genesis 2, within the Yahwist account, Eve appears last and therefore occupies the position of greatest narrative significance.

The American writer and activist in the biblical equality movement Rebecca Groothuis also drew attention to these features. She argued that the name Adam does not specify sex and, in a literal sense, derives from the Hebrew for “earthly” — that is, “from the ground.” From this, Groothuis concluded that the human is called “adam” because he functions as a representative of humankind, and his identity is defined primarily by human nature rather than by male sex. Before the woman appears, Adam, on her reading, remains a human being with an undefined sexual form.

Groothuis also appealed to Genesis 5:1–2, which states that God created male and female and called both of them “adam”: “God created the human being; He made him in the likeness of God. He created male and female and blessed them. When He created them, He called them ‘adam’ [human].”

The American Christian author Donald Joy proposed a biological analogy. In early development, an embryo has a female form, and sex differences become visible only by the ninth week. As Groothuis noted, this can be read as repeating the same pattern: both in the creation story and in human development, sex is initially indeterminate, and differentiation into male and female emerges later. Joy expressed it like this: “We all begin the same in Adam, but we also all begin the same in the embryo. Creation is repeated in every conception.”

Groothuis emphasized that her proposal does not claim the status of strict theological dogma. At the same time, she argued that the biblical text permits such a reading. The man was not the “first” being: first there was a human-androgyne, and the woman did not arise merely as an “appendix.” Rather, God created a humanity in which man and woman together constitute “Adam.” He is human, and she is human.

Against the Theory of Adam’s Androgyny

By the late 20th century, debates over the androgyny hypothesis were conducted largely within Protestant theology, where the most developed objections were also formulated. For that reason, it is reasonable to focus on Protestant interpretations, which have been especially influential and analytically productive in this discussion.

Gerhard von Rad and Werner Neuer

The 20th-century German Protestant theologian Gerhard von Rad read Genesis primarily through a linguistic lens. He highlighted a specific feature of Genesis 1:27: the text first uses a masculine singular pronoun (“him”) and then shifts to a plural form (“them”) in the following clause. For von Rad, this grammatical change indicates that the passage was not originally describing a two-sexed individual. If an androgynous person were intended, the plural “them” would be unnecessary. Von Rad also cautioned against an overly “spiritualized” interpretation, stressing that the human being is created in the image of God not only in a spiritual sense, but also as a bodily creature.

A related position was advanced by the German evangelical pastor Werner Neuer. He argued that God intended humanity from the outset as sexually differentiated: male and female belong to the original design rather than being introduced later. In Neuer’s account, the notion of an androgynous Adam entered Christian discourse from external sources — through Plato, through the Jewish thinker Philo (shaped by Platonism), and through Gnostic traditions.

Proponents of the androgyny hypothesis responded by noting that while the motif is indeed present in Plato, medieval theologians (as they argue) stripped away pagan elements and reinterpreted it within a Christian framework. On this view, Plato presents androgyny as an indivisible unity in which opposites collapse into one another, whereas Christian philosophy reframes it as a dynamic unity: male and female remain distinct yet mutually complementary.

The cause of the “split” is also explained differently. In Plato, it is simply Zeus’s decision, and the dialogue offers no clear resolution. Medieval Christian thought, by contrast, described the possibility of healing through love or chastity, together with hope for salvation and the restoration of wholeness in the Kingdom of God.

Neuer further maintained that affirming a two-sexed Adam would fundamentally reshape Christian accounts of human nature and sexuality. If so, sex would not belong to God’s original plan, but would appear as something secondary, later, and even distorted — a kind of degeneration from an original human condition.

In support of his argument, Neuer offered three main points. First, Genesis 1:27 states: “God created … them, male and female.” Here he agreed with von Rad that the plural “them,” rather than the singular “him,” suggests two persons. Second, Genesis 5:2 reads: “Male and female he created them, and he blessed them.” Again, the plural form, in his view, excludes the idea of a single androgynous individual. Third, in Genesis 1:28, immediately after the creation of human beings, God addresses them with the command: “Be fruitful and multiply.” For Neuer, this directive is clearly oriented toward a pair, not toward one androgynous being.

Edward Noort

The Dutch theologian and Old Testament scholar Edward Noort offers a detailed reading of how Genesis depicts the emergence of the first humans:

“27aa And God created ha’adam (humankind) in His image,

27ab in the image of God He created him,

27b zakar u-n’qebah bara otam (male and female He created them).”— after Edward Noort

Noort observes that the expression zakar u-neqebah in the Pentateuch consistently refers to a concrete male and a concrete female — either a human pair or the male and female of animals. The formula appears in laws concerning ritual impurity, vows, censuses, and sacrifices, as well as in the Flood narrative, where it clearly denotes an animal pair. On this basis, he concludes that Genesis 1:27 is not describing a mythical androgynous being but the first human pair.

Noort also argues against de Moor, who connects the biblical text with ancient Near Eastern myths of divine duality. Noort accepts that such parallels may exist, but he maintains that the author of Genesis did not directly adopt these myths. For Noort, the text is oriented less toward explaining the past than toward indicating the future. This is why the Adam genealogy follows immediately after the creation account. Humanity continues only through the birth of children and therefore — through sexual difference. In this framework, Genesis 1:27 incorporates the distinction between man and woman into the created order from the outset.

Wayne A. Grudem and Richard M. Davidson

In the twenty-first century, the American evangelical theologian Wayne A. Grudem also examines the hypothesis of an androgynous Adam. He argues that Groothuis is mistaken and that the term adam in the opening chapters of Genesis functions with multiple meanings. At times it refers to “the human being” in general, but in several passages it denotes “a man” more specifically. Thus, in Genesis 2, the text states that before Eve’s creation “no helper was found corresponding to Adam.” Grudem concludes that Adam was already sexually differentiated, and that adam in this context should be read as “man.” An egalitarian interpretation, he argues, would undermine the narrative purpose of Eve’s creation.

Grudem continues by claiming that if Adam were originally androgynous or sexless, then at creation he would have been neither a male human nor a female human. In that case, he would not have been human in the sense in which humans exist today. Moreover, it was Adam — not humankind as a whole — who received the command not to eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. At that point Eve did not yet exist, and Adam alone represented humanity. If Adam were androgynous, Grudem argues, he could not function as our representative, because he would not be like us.

The American Old Testament scholar and theologian Richard M. Davidson emphasizes in his work that what matters is not hypothetical pre-literary sources behind the Pentateuch but the text in its final redaction. This final form, he argues, places the opening chapters of Genesis at the beginning and makes them the theological basis for reflection on human sexuality. For Davidson, these chapters are not two unrelated documents but a single composition in which sex and marriage are integrated into the Creator’s overall design.

Davidson treats Genesis 1–2 as a primary framework for interpreting human sexuality. On his reading, sexual difference is not merely asserted; God’s intention for the human person is disclosed. He regards the distinction between the sexes as fundamental to what it means to be human: one cannot speak of “human being” without implying “male and female.” From this perspective, sexuality is embedded by God in the very structure of human existence. At the same time, Davidson finds no textual basis for describing the first human as a being that unites both sexes. When the woman is created, Adam does not change in nature — he only loses a rib. God creates him with an inherent orientation toward a partner. The episode with the animals (Genesis 2:18, 20) indicates that none of them could serve as “a helper corresponding to him.” Only the creation of the woman discloses to the man the fullness of his sexuality, which, for Davidson, was present in him from the beginning.

***

The debate over Adam’s androgyny — from Gregory of Nyssa and Maximus the Confessor through Böhme, Baader, Solovyov, and Berdyaev to Trible, de Moor, and their critics — indicates that the biblical text can sustain multiple interpretations. How should we understand ha-adam (Hebrew ha-’adam — “the human,” “humankind”)? Should sexual difference be treated as original, or as temporary? These questions remain unresolved and require further study. Yet the continuation of such debate is itself significant: it expands the interpretive horizons for reading Scripture.

🙏 This piece is part of the article series “Queer Theology of the Old Testament”:

- What Gender Is God in the Old Testament?

- Adam Before Eve: Male or Androgynous? Theological Debates From the Church Fathers to the Present Day

- A Queer Theological Reading of Leviticus 18:22: “Do Not Lie With A Man As With A Woman”

📣 Subscribe to our Telegram channel (in Russian): Urania. With Telegram Premium, you can translate posts in-app. Without it, many posts link to our website, where you can switch languages — most new articles are published in multiple languages from the start.

References and Sources

- Бердяев Н. А. Смысл творчества: опыт оправдания человека. 1916. [Berdyaev N. A. – The Meaning of Creativity: An Essay in the Justification of Man]

- Григорий Нисский. Об устроении человека. [Gregory of Nyssa – On the Making of Man]

- Иванова Т. А. Развитие платоновской идеи андрогина в гностической и средневековой философии. 2021. [Ivanova T. A. – The Development of Plato’s Idea of the Androgyne in Gnostic and Medieval Philosophy]

- Соловьёв В. С. Сочинения в 2-х томах. 1988. [Solovyov V. S. – Works in Two Volumes]

- Baader F. Sämtliche Werke. 1851–1860. [Baader F. – Complete Works]

- Böhme J. Mysterium Magnum: or, an exposition of the first book of Moses, called Genesis. 1656.

- Böhme J. The high and deep searching out of the threefold life of man. 1650.

- Davidson R. M. Flame of Yahweh: sexuality in the Old Testament. 2007.

- de Moor J. C. The duality in God and man: Gen 1:26–27. 1997.

- Groothuis R. M. Good news for women: a biblical picture of gender equality. 1997.

- Grudem W. A. (ed.). Recovering biblical manhood and womanhood: a response to evangelical feminism. 1991.

- Grudem W. A. Evangelical feminism and biblical truth: an analysis of more than 100 disputed questions. 2004.

- Maximus the Confessor. On difficulties in the Church Fathers: The Ambigua

- Neuer W. Man and woman in Christian perspective. 1991.

- Noort E. The creation of man and woman in biblical and ancient Near Eastern traditions. 2000. [

- von Rad G. Genesis: a commentary. 1961.

- Stolper P. The man–woman dynamic of ha-adam: a Jewish paradigm of marriage. 1992.

- Tags:

- Theory