A Homosexual Scene in Norway’s Prehistoric Art: The Bardal Petroglyphs

In Norway, among prehistoric rock carvings, there are images of humanoid figures that appear to hint at a homosexual sex act.

- Editorial team

On the Bardal farm in the municipality of Steinkjer is one of the largest collections of rock art in the region - the Bardal petroglyphs (Bardalfeltet).

A petroglyph is an image carved or pecked into stone, made by ancient people.

One rock surface contains images from different periods - from the Stone Age to the Iron Age. Later figures are often carved over earlier ones, creating a layered composition. Taken together, the images form a kind of “story” about life from around 4000 BCE to the beginning of the Common Era.

The carvings are typically grouped into two broad categories: hunting and farming. The earliest layer includes hunting scenes and animals - deer, whales, and seabirds. A later layer includes boats, human figures, horses, and various geometric signs.

Discovery History and Geography

The petroglyphs were first described in 1896 by the teacher and archaeologist Knut H. Lossius. Over the following decades - roughly 40 years - the site attracted the attention of other specialists and gradually became the subject of systematic study.

The field lies about 11 kilometers from the town of Steinkjer. Together with the Stjørdal area, this region contains the largest concentration of rock carvings in Central Norway. Archaeologist Anders Hagen noted that Bardal’s location - where mountains, forests, and the coast meet - may have given the place a particular status and made it significant for ancient hunters.

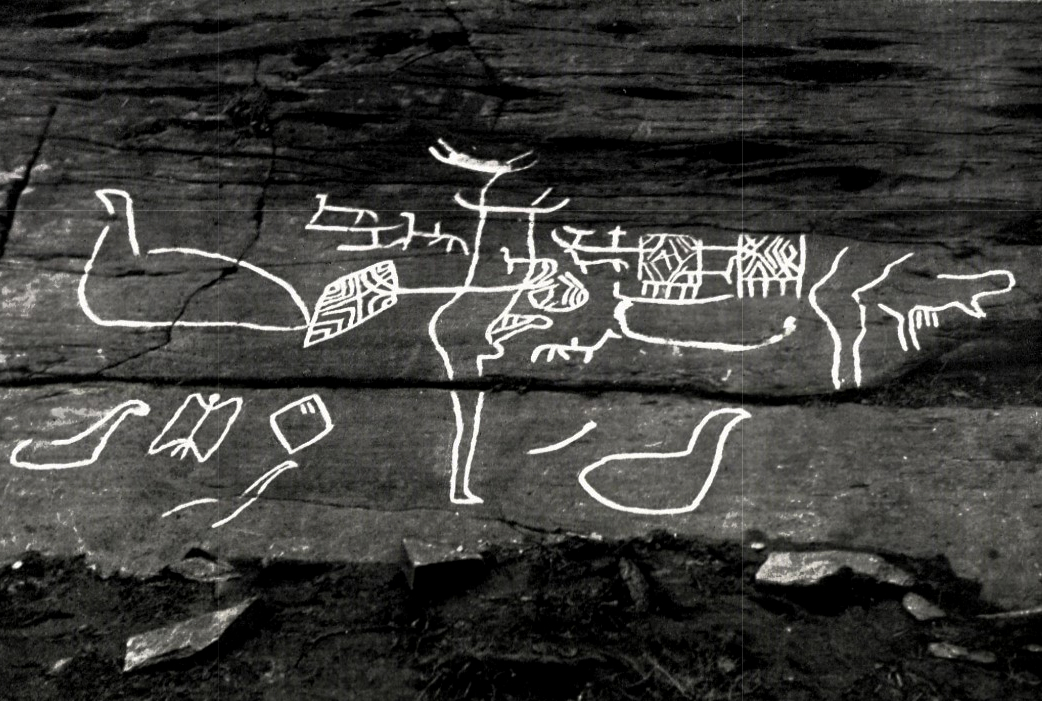

The main panel, Bardal-1, is on a southern slope near the farm of the same name and is among the largest in the region (26 × 13 meters). The rock is divided by a vertical crack into two sections; on its western side, almost 400 images have been recorded.

Images of Farmers

These scenes are usually attributed to the farming layer of the Bronze Age (1800–500 BCE). The most common motif is boats; other elements include horses, spirals, and cup-shaped hollows (cup marks - small, round depressions pecked into the rock).

The largest boat, 4.5 meters long, is decorated with 90 vertical lines, which likely represent rowers. It is among the largest boat images known in Scandinavia. During this period, water levels were higher, and a shallow bay lay nearby. On this basis, researchers suggest that Bardal may have functioned as a contact and meeting place for different groups. The carvings may also reflect an effort by seafarers to mark their presence in this landscape.

Images of Hunters

The hunting images are considered the earliest; about 50 have survived. The motifs include animals close to life-size - deer, moose, and even a six-meter whale, probably a beaked whale. There are also five bird figures and one image of a bear.

Of particular interest are rare anthropomorphic figures: a male figure 114 cm tall with an erect penis, and two scenes that may depict same-sex anal sex.

A Possible Homosexual Scene

Anthropomorphs are ancient images that resemble human figures. They may have a head, arms, and legs, but they often feature disproportionate shapes or fantastical details - horns, tails, or wings.

In one of Bardal’s hunting-era areas, several anthropomorphic images survive, dated to roughly 4000–2700 BCE - the Neolithic period, when metallurgy had not yet reached this region. Notably, this section was not overlain by later carvings from the farming era.

Three male silhouettes stand out, positioned apart from the deer figures. Nearby are four geometric lozenges (diamond shapes), four birds (probably ducks), and an unusual “winged” anthropomorph resembling a butterfly. The relationship between these motifs remains uncertain. At the same time, the anthropomorphic figures are rendered in a more complex and stylized manner than the rest of the panel. Each has distinct features, which may indicate different phases of production or the work of different carvers.

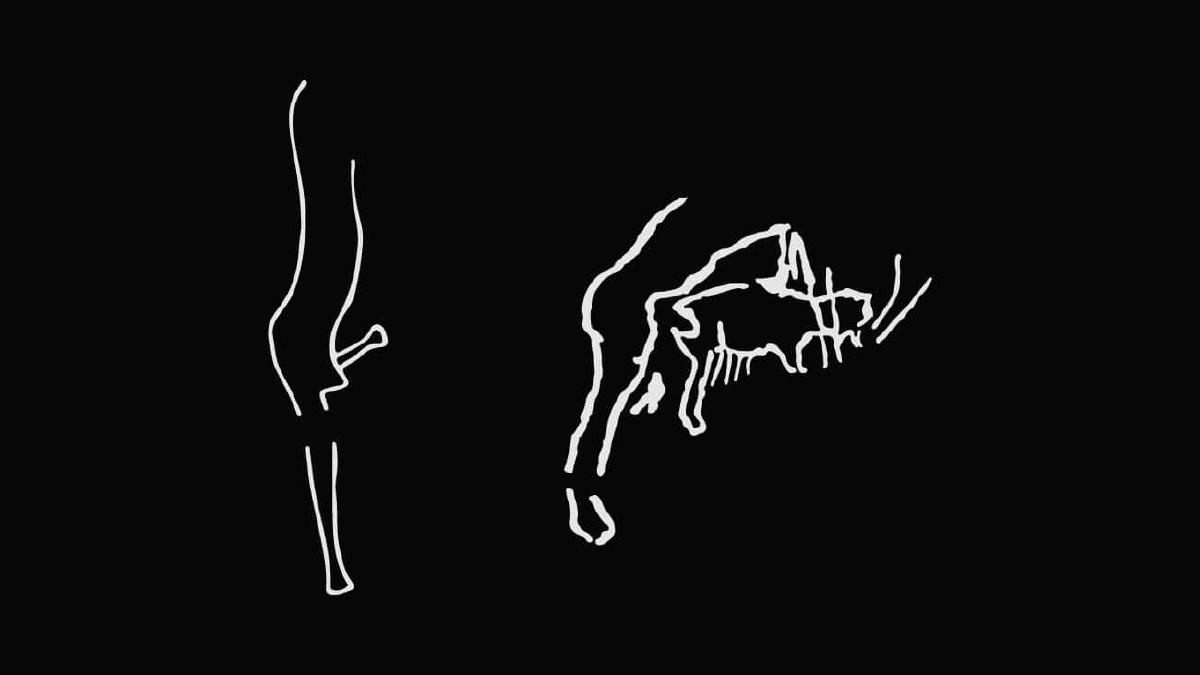

Two human figures are shown engaged in sex. On the smaller figure, several lines may indicate either breasts or arms. Beneath the abdomen, a series of vertical strokes is visible - possibly a schematic depiction of pubic hair.

A larger, headless figure penetrates the smaller one. The placement of the penis suggests anal contact. Despite the difference in scale, the scene appears internally coherent: there are no signs of violence, and the movement of both figures is conveyed as coordinated and consensual.

To the left of the pair is another headless man with an erect phallus. His body is more proportionate, and two lines beside him may indicate arms; one likely touches the penis, suggesting masturbation. This figure may function as an observer, introducing a voyeuristic element. It is notable that the artist does not detail the heads and instead emphasizes the lower body, as if intentionally obscuring the participants’ identities.

By contrast, sex between a man and a woman is more often assumed to involve face-to-face contact, commonly described as the “missionary position.” A “from-behind” position, in turn, is more often associated with homosexual men.

Ritual Male Intimacy and Scholarly Interpretations

In 1938, the archaeologist Gustaf Hallström proposed that the image depicts a man and a woman. He also argued that the intercourse is vaginal rather than anal. In addition, Hallström drew attention to two vertical lines in front of the smaller figure (in the illustration, they are not highlighted with paint). In his interpretation, these lines could represent a third participant, allowing the scene to be read as group sex.

Ethnographic evidence indicates that in some cultures, homosexual practices can be understood as part of the life cycle. For example, among the Sambia of Papua New Guinea, an initiation ritual involves older men transferring semen to boys, treating the act as a means of endowing them with strength. In this framework, semen is equated with milk, and the penis is symbolically linked to the breast that “nourishes” the younger generation.

In the 1990s, the archaeologist Tim Yates suggested that some Scandinavian rock carvings depict not conventional marital scenes, but unions between men. He proposed that such motifs might symbolize masculinity or belong to initiation practices involving adolescent boys.

The British archaeologist Ian Hodder also studied hunter-gatherer rock art and connected it to ideas of masculinity. Yates developed this approach further by drawing attention to martial images of men with clubs and spears, and by arguing that exaggeratedly large phalluses in such scenes functioned as an additional sign of power.

Although ritual forms of homosexuality likely existed in many prehistoric communities, they may also have been treated as practices at the margins of what was considered normal. Rock art - including the Bardal panels - may record such male rituals without women and with restricted access, which has parallels in a number of modern, ethnographically documented examples.

In European prehistoric art, male sexuality is often depicted frequently and emphatically, while female figures appear far more rarely. This imbalance may suggest that the production and control of visual narratives largely lay with men. At the same time, the small number of scenes that can be interpreted as homosexual can hardly be taken as a direct reflection of social reality. Yet, when considered alongside Melanesian traditions and other ritual practices, such images warrant separate attention.

🦴 This piece is part of the article series “Prehistoric LGBT History”:

- Homosexuality Among Neanderthals

- The First Homoerotic Image in History — The Addaura Cave Rock Engravings

- A Prehistoric Double Phallus From the Enfer Gorge

- A Homosexual Scene in Norway’s Prehistoric Art: The Bardal Petroglyphs

- A 4,600-Year-Old Burial of a “Third-Gender” Person: What We Know and What Is Disputed

📣 Subscribe to our Telegram channel (in Russian): Urania. With Telegram Premium, you can translate posts in-app. Without it, many posts link to our website, where you can switch languages — most new articles are published in multiple languages from the start.

References and Sources

- Hagen A. Helleristningar i Noreg, 1990. [Hagen A. - Rock Carvings in Norway]

- Nash G. The Subversive Male: Homosexual and Bestial Images on European Mesolithic Rock Art, in Indecent Exposure: Sexuality, Society and the Archaeological Record, 2001.