The First Homoerotic Image in History — The Addaura Cave Rock Engravings

Acrobats, a ritual dance, or same-sex intercourse?

- Editorial team

The Addaura Caves

Prehistoric art appeared in Sicily noticeably later than in some other parts of Europe. The earliest traces of artistic activity in southern Italy are usually dated to roughly 16,000–15,000 years ago. By comparison, in Spain, prehistoric art sites are known from about 40,000 years ago.

In Sicily there is the Addaura complex: three grottoes on the slope of Monte Pellegrino (often called simply Mount Pellegrino). A grotto is not a “deep cave” but rather a semi-underground niche in the rock: the front is open, while the interior is shallow. Such hollows form through erosion, as water and wind gradually “eat away” the stone.

Numerous rock engravings have been preserved on the walls at Addaura. They were discovered in the mid-20th century. In 1943, during World War II, after the Allied landing in Sicily, the grottoes were used as ammunition depots. A chance explosion occurred, part of the walls collapsed — and this revealed images that had previously been covered by debris and layers of rock.

The first person to study the finds in detail was the Italian archaeologist Jole Bovio Marconi. She described and analyzed the images and published her results in 1953. But since 1997, access to Addaura has been closed: the cliffs there may collapse. By 2012, the condition of the site had worsened — due to neglect and acts of vandalism.

The First Depiction of a Homosexual Sex Act in History?

At roughly 70 meters above sea level, archaeologists found engravings attributed to the Epipaleolithic. The Epipaleolithic is a transitional period between the Late Paleolithic (Late Stone Age) and the Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age): the climate was changing, ways of life were gradually becoming more complex, people were improving tools, and more often living in more stable groups. This period is usually dated to roughly 14,000–12,000 years ago — and the Addaura engravings are generally considered to be about the same age.

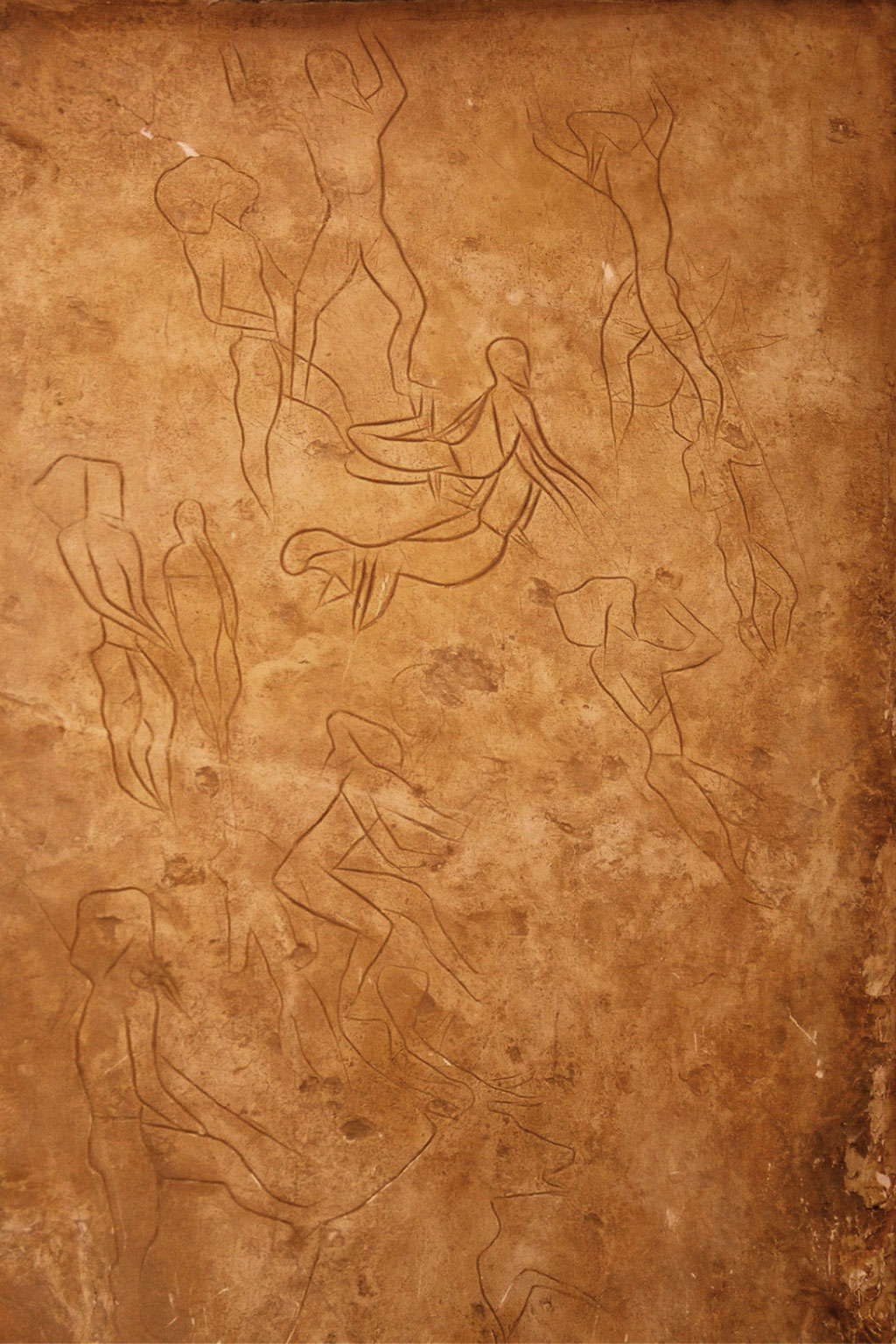

One of the key spots in the complex is a grotto known as the “Cave of the Inscriptions.” In the deepest part, about two–three meters above the ground, lies the main frieze — a long “band” of images. The frieze runs for about 2.5 meters, and the figures are arranged diagonally. Researchers distinguish 17 human figures and 15 animals on it.

Some lines overlap others — which means the images were not made all at once: later, someone added new figures or redrew older ones. This is normal for prehistoric art: the rock “lived” together with people and their traditions.

The British historian Alan Bullock wrote in one of his works:

“The prehistoric era shows that as early as the period from 9660 to 5000 BCE, Mesolithic rock art on cave walls in Sicily depicted scenes of homosexual relationships.”

— Alan Bullock, British historian

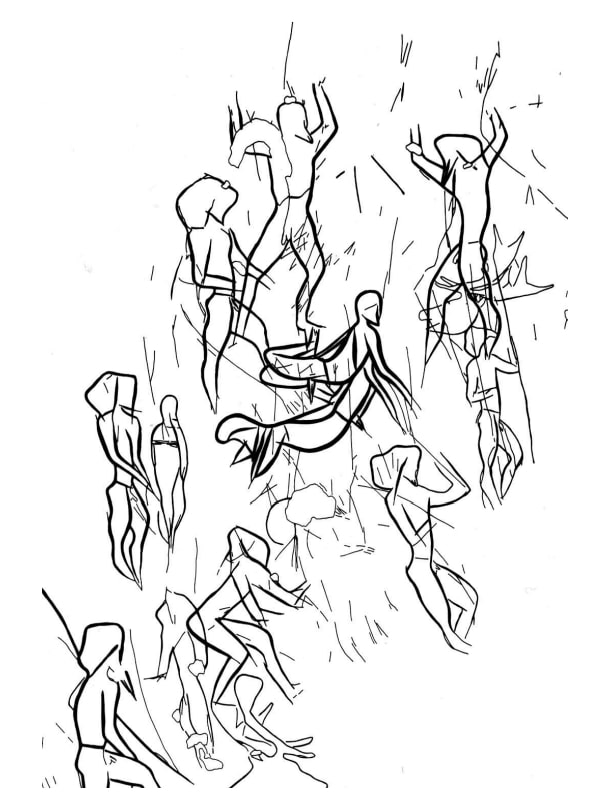

The scene Bullock refers to is known in scholarly literature as the “Acrobats of Addaura.” It is precisely this scene that provokes the sharpest debate: what, exactly, is being shown? One group of researchers sees a depiction of sexual contact between men. Another believes it is a ritual scene — for example, a rite connected with sacrifice or an ordeal.

There are many animals on the frieze: bulls, wild horses, deer. But the eye is usually caught by the center — by the group of human figures.

Two “acrobat” figures have erect penises. Their bodies are strongly arched — which makes the scene look tense and “in motion,” as if it captures a moment of action. Other people stand around them, forming a circle. Such a ring around a central episode is often taken as a hint of a rite or a meaningful act, rather than a random everyday scene.

A contemporary Italian researcher, Paola Budano, analyzed in detail the figures surrounding the center: how the legs are placed, where the hands point, and whether there are ornaments. She drew attention to masks with long bird beaks. In her view, these characters may be participants in a dance — that is, a ceremony in which movement and costume play an important role. The poses look like a sequence of gestures, as though the artist was recording “steps” or phases of motion.

All these people resemble one another: roughly the same height, similar build, unclothed. If there is something on their heads, it looks uniform — either hairstyles or headdresses. Some characters wear “beaked” masks, but not all.

Among the people around the two acrobats, Budano identifies two or three female figures. One of them can also be interpreted as male — there are not enough clear markers. The female figures are distinguished by the absence of male genitals, softer outlines of the chest and abdomen, and less “muscular” rendering in the drawing. Importantly, these female figures stand upright and motionless — so, most likely, they are not dancing, but observing or participating in a different way.

Where such a rite might have taken place is also unclear. There are two main versions: either outdoors, because there are many animals nearby, or inside the grotto itself, because the entire composition is placed on the wall in the depth of the shelter.

Now — about the two central figures separately.

The Upper Figure. The person is shown in a very strange, almost “broken” pose: the legs are bent backward, with the feet lifted toward the buttocks. Only the right foot is visible. The penis is depicted as erect, but there is an alternative interpretation: it may not be genitalia, but an elongated object between the legs, extending beyond the line of the buttocks. If so, the right “foot” could be part of this object rather than a leg.

The waist is emphasized, the torso arched backward. The arms are stretched forward and look too long for the body. The hands taper to a sharp point, and this pointed end overlaps the legs of the lower figure. At shoulder level, there are lines that connect to a cut or slash crossing the torso diagonally and running toward the buttocks — this may be an element of ritual costume, straps, or simply a conventional sign. The head is not fully covered, but a “bird beak” is visible on it — less pronounced than on some of the surrounding figures. The right eye seems to be indicated by a slit.

The Lower Figure. It is partially covered by the upper one, so there are fewer details. The legs are bent, but not fully legible. The male genitals are shown clearly, with the penis erect. Two parallel lines extend from the genital area and continue on the opposite side of the body: this may be part of the compositional device, straps, ropes, or a symbolic detail.

The waist is rendered more simply than in the upper figure: from the shoulders to the legs there is an almost straight line. The arms are also stretched forward, but they are shorter and thicker than those of the upper figure, and they too end in a point. The neck is marked by a bundle of radiating lines. The face is not drawn. The hair is conveyed by a few strokes, but there is a version that these are not hair, but a headdress.

Theories

Researchers who have studied these engravings most often focus on the two central figures. How the overall scene is interpreted depends on what, exactly, these reclining (or “laid out”) characters are doing. Their almost horizontal bodies look unusual — which is why so many contested readings have emerged.

Homoeroticism

Some scholars — including the discoverer Jole (also spelled Djole) Bovio Marconi — initially saw a homoerotic subject in the two central male figures: an image connected to sexual desire between men. This version is especially popular in queer-history writing.

It is usually retold like this: a group of people stands around two men. The central figures have erect penises. Parallel lines are visible on their bodies; these are described as lines connecting the neck, buttocks, ankles, and the genital area. One of these lines is sometimes interpreted symbolically — as “male energy,” or even as an allusion to ejaculation. In the boldest retellings, this becomes a story of a ritual initiation with sexual overtones, or even an orgy.

But this reading has a weak point: it is impossible to prove from a single image. The scene may be an early example of homoerotic art, but it remains a hypothesis. Moreover, Bovio Marconi herself later said that the meaning of the composition as a whole is unclear.

Marconi later supported another interpretation as well: that what we are seeing could be acrobats performing a stunt. As she admitted, “In any case, the meaning of the composition is not clear, and I hope that others may find an interpretation that escapes me.”

Acrobats

Another group of researchers argues that this is neither sex nor execution, but an acrobatic performance: people are shown in the middle of a complex stunt in which the body is deliberately arched and held in an unusual pose.

The Italian researcher F. Mezzena proposed a “flying acrobats” interpretation. In his view, some participants “launch” a person into the air while others catch them — like a coordinated group act. A key detail is that the acrobats’ male traits, including erection, are emphasized. Within this theory, that is explained not as “a sex plot,” but as fertility symbolism: in many ancient cultures, sexual characteristics and ideas of fertility were often used in rites meant to secure reproduction and the well-being of the community.

The same scene is sometimes linked to initiation — a rite of passage in which a person is moved from one status to another: for example, from adolescent to adult, or from “uninitiated” to a member of the group. But we do not know what kind of rite it would have been.

Those who favor a ritual reading often point to the “bird” masks — faces with beaks. They are understood as part of a ceremony: in rituals, a mask often means that a participant temporarily becomes not “themselves,” but a role — a spirit, an ancestor, a totemic being. In such beliefs, a bird is not uncommonly associated with the “spirit world” or the supernatural.

Condemned to Death or Sacrifice

There is also a darker interpretation: the central figures are people being killed.

Supporters of this view read the lines on the body as ropes. In their opinion, a rope runs from the head to the ankles: the body is, as it were, cinched tight, and the pose resembles not a stunt but a condition after loss of muscular control. The researcher Blanc in the 1950s directly suggested that the image depicts a ritual execution. He drew on ethnographic parallels — descriptions of rituals among different peoples recorded in modern times.

According to Blanc, both figures die by self-strangulation — choking caused by a tightened rope, when a person can no longer breathe on their own. He also connected the erection to asphyxiation: in hanging, a persistent erection can indeed occur as a physiological effect. In addition, he noted the absence of a “penile sheath” (a protective leather cover for the penis found in some cultures and sometimes shown in images). For Blanc, this was an argument that we are not looking at an everyday scene, but specifically at a ritual death.

A related hypothesis is sacrifice. In that case, the central figures do not “execute themselves”; they are killed as part of a rite led by a shaman or another ritual leader. The researcher G. Bolzoni supported precisely this line of explanation. He believed the frieze includes a figure of a man carrying another person. He understood the carried person as already dead — allegedly bound by the legs and neck. Bolzoni then proposed reading the frieze as “two scenes side by side”: in the center, the killing itself; to the side, the carrying of the body to a burial place.

The problem with this version is that the image does not show clearly that the second “acrobat” is truly being carried: the details can be read in more than one way, and not all scholars accept this kind of “montage” of adjacent scenes.

Ritual Dance

Paola Budano offers yet another framework: not “sex or death,” but a circular ritual dance of men connected with initiation. In that case, the surrounding figures are the dancers, and the central characters inside the circle express the meaning of the rite.

If the central figures are dead, the dance can be understood as a symbolic passage “from life to death” — a ritual about the boundary between worlds. If they are alive, the scene may signify coming of age: the transition from childhood to maturity, that is, initiation.

In support of the initiation reading, Budano points to details not present in the other figures. For example, one eye is emphasized in the upper central figure — which can be read as a sign of “special sight,” spiritual awakening, or a change of status. Another distinguishing detail is the erect penis of the central characters, whereas the other participants in the circle do not display such features.

***

And yet, even with many competing interpretations, the central motif remains the same: two figures with emphasized male sexuality. Because of this, many authors maintain the conclusion that the scene may be extremely early — possibly one of the first — homoerotic images in the history of art.

🦴 This piece is part of the article series “Prehistoric LGBT History”:

- Homosexuality Among Neanderthals

- The First Homoerotic Image in History — The Addaura Cave Rock Engravings

- A Prehistoric Double Phallus From the Enfer Gorge

- A Homosexual Scene in Norway’s Prehistoric Art: The Bardal Petroglyphs

- A 4,600-Year-Old Burial of a “Third-Gender” Person: What We Know and What Is Disputed

📣 Subscribe to our Telegram channel (in Russian): Urania. With Telegram Premium, you can translate posts in-app. Without it, many posts link to our website, where you can switch languages — most new articles are published in multiple languages from the start.

References and Sources

- Budano P. The Addaura Cave: Dance and Rite in Mesolithic Sicily, Open Archaeology, 2019.

- Mussi M. Earliest Italy: An Overview of the Italian Paleolithic and Mesolithic, 2001.

- Bolzoni G. Nuove osservazioni sulle incisioni della grotta Addaura del Monte Pellegrino (Pa), Atti della Società Toscana di Scienze Naturali, Serie A, 1985. [Bolzoni G. – New Observations on the Engravings of the Addaura Cave on Monte Pellegrino]